The Teesta River Basin is widely known for the Indo-Bangladesh water-sharing dispute and the political tussle between the government of West Bengal and India’s central government on “giving” Teesta water to Bangladesh. However, recent events in the basin have cast light on other issues as well, the biggest being the revival of demand for a separate Gorkhaland.

Historically, Darjeeling and the surrounding regions were passed around among the regional powers of Sikkim, the Gorkhas, Bhutan, and the British until 1947, when they became a part of independent India. The British brought tea along with them, and the region, especially Darjeeling, prospered. However, most of the positions of wealth and power were captured by Marwadis and Bengalis respectively, while the local tribes (Lepcha, Limbu etc.) as well as the Nepalis who had migrated to work on the tea estates found themselves on the lower rung of the ladder. With very little in common with the Bengali and Marwadi languages and cultures, it was only a matter of time before the Gorkhas would aspire for a separate state.

That the Darjeeling Hills see themselves as separate from Bengal is evident from the municipal elections which were held there mid-May this year. Gorkha Jan Mukti Morcha (GJM), the political party currently leading the struggle for Gorkhaland, maintained its hold over the hills by winning the municipalities of Darjeeling, Kurseong, and Kalimpong, while Mamata Banerjee’s All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) managed to scrape by with Mirik. The demand for Gorkhaland is a hundred years old and only recently had the tone softened, but shortly after the municipal elections, Banerjee declared Bengali as a mandatory language in all schools across West Bengal, and the hills erupted again.

The Building Blocks of Gorkhaland

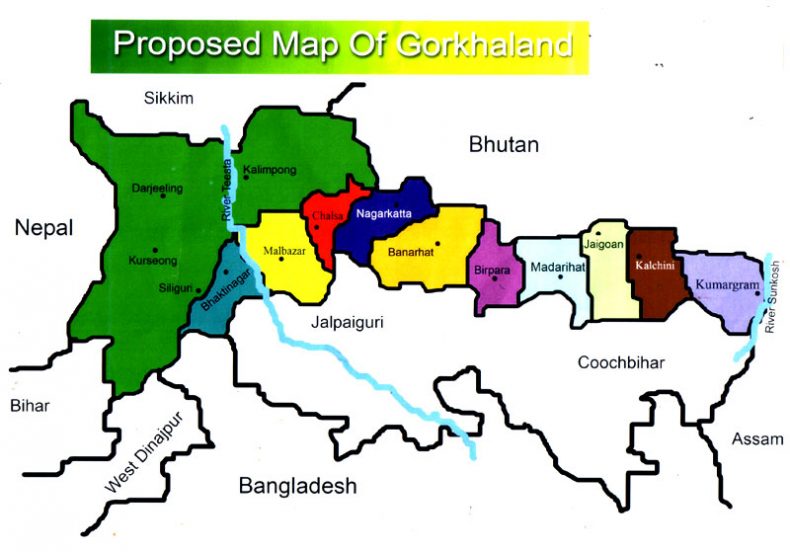

The proposed area under Gorkhaland is the hilly region of extreme north Bengal bordering Sikkim; Siliguri and some parts of Jalpaiguri (the Dooars), stretching toward Assam in the east have been a relatively recent addition.

Proposed Map of Gorkhaland. Picture Credit: The Darjeeling Chronicle (via Facebook messenger).

The current area under the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration, a semi-autonomous governing body which succeeded the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) in 2011, is about 3,300 square kilometers (sq km), and with a population of about 1.2 million, has three assembly seats. With not even a full Lok Sabha seat under its remit, the GTA-administered area is too small to merit statehood. However, with Siliguri and the Dooars, the area proposed under a separate Gorkhaland more than doubles to 6500 sq km and its population expands to 3.2 million, which translates into 20-25 assembly seats, and a whole Lok Sabha seat.

While the hilly regions – Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Kurseong, and Mirik – house a predominantly Gorkha population, the inclusion of Siliguri and Dooars in the proposed area of Gorkhaland has raised eyebrows as the residents of these areas are largely Bengalis and Rajbanshis. Further, this inclusion means an overlap with the proposed area of Greater Cooch Behar, another state in demand, this time by the Rajbanshis. Yet without the inclusion of Siliguri and Dooars areas, Gorkhaland cannot hope to qualify as a state.

The Position and Role of the Teesta River

The Teesta is the principal river in the region. The area proposed under Gorkhaland includes the Teesta River upstream of the Gajaldoba barrage in the Dooars region in Jalpaiguri district. Further, the inclusion of the Dooars region in Gorkhaland hints at the slim chance that the West Bengal government might lose control of, among other dams in the upper reaches of the Teesta, the Gajaldoba barrage, which is central to the Teesta dispute between India and Bangladesh.

In 2011, the Teesta talks between India and Bangladesh failed due to Banerjee’s refusal to cooperate at the last minute. She simply refused to open the gates of the Gajaldoba for Bangladesh, declaring that the water was held back for the needs of the population of North Bengal. Water being a state subject as per the Indian Constitution, the barrage gives the West Bengal government significant leverage over the sharing of the Teesta (and over the central government) by which Banerjee looks to consolidate votes in a not-so-supportive North Bengal.

If formed, Gorkhaland will be the upstream neighbor to West Bengal. Even if West Bengal does retain the Gajaldoba barrage, an independent Gorkhaland, with or without the graces of the central government, will still be able to control Teesta’s flow to Gajaldoba and the Bengal plains, thus reducing West Bengal’s control over the Teesta drastically. The GJM knows this; amidst the strikes, rallies, and violence, GJM chief Bimal Gurung has already warned that he will halt ongoing hydro projects, including the Teesta Lower Dam III and Teesta Lower Dam IV, on the Teesta River as a “non-cooperation movement against the West Bengal government.” Whether that statement materializes into reality is another story, but the fact remains that an independent Gorkhaland could certainly do so.

There are economic dimensions to West Bengal’s hypothetical loss as well. The Darjeeling Hills are economically important for West Bengal as they have flourishing sectors of tourism and tea, with the Teesta River playing an important role in both. In 2014 alone, more than 600,000 tourists visited the areas under the GTA. In the same year, the areas of Darjeeling and Dooars produced over 187 million kilograms of tea, which amounts to about 60 percent of the tea production of West Bengal. Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri districts have the highest per capita incomes in West Bengal (ranked 1st and 3rd respectively in the State Development Report issued by the Government of India’s Planning Commission in 2010) and tea, a financially lucrative cash crop, is an important contributor. If Gorkhaland becomes a separate state, West Bengal will lose two of its more prosperous districts and see a substantial reduction in its revenue from tea and tourism.

The entire scenario plays out in that part of the Teesta basin which is also known as the Siliguri corridor — a narrow strip of land connecting the northeastern states of India with the rest of the country. Popularly known as the “Chicken’s Neck,” the corridor is sensitive on multiple levels. First, it is home to a disputed transboundary resource (the Teesta River) and is squeezed between four neighboring countries — Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and China. Second, the railway network which passes through this corridor connects to military bases in the northeast and is essential to provide the troops with supplies and reinforcements. Third, it is a highly sensitive and socially fragile region: it faces a high incidence of poverty and economic inequality, is home to some of the most backward districts of West Bengal, has seen the birth of the Naxal movement, and now experiences a significant influx of “outsiders” i.e. Nepalis and illegal Bangladeshi migrants. Fourth, the region is impacted by climate change and has been grappling with environmental disasters such as extreme floods and droughts, which directly affect the Teesta River. Any redrawing of political borders in this area has to be done with utmost care and sensitivity, keeping security, economic, and environmental priorities in mind.

Simmering But Not Spilling Over

The struggle for Gorkhaland continues in the Darjeeling Hills and has taken a violent turn, but the creation of a new state is not in sight. For starters, the inclusion of Siliguri and the Dooars area in the proposed Gorkhaland territory has drawn criticism as these areas are not predominantly Gorkha, thus weakening their claims. This was manifest in the decision of the Justice Shyamal Sen Commission, which handed over only five “mouzas” (a type of an administrative unit) from the Siliguri and Dooars region to the newly formed GTA in 2012. The West Bengal government has publicly apologized for forcing the Bengali language on the hills, but has been resolute in keeping the state unified. In Banerjee’s rather poignant words, “Bengal cannot suffer the pain of yet another partition.”

The BJP is currently trying to make headway in West Bengal, and fears that creating Gorkhaland would seriously hamper its prospects in the rest of the state. The state’s BJP cell too has openly stated that even though they empathize with the agitators and stand for their development, they do not support the creation of Gorkhaland for now, and will not uphold the “demand to turn a village or municipal corporation into a state.”

However, there is an alternative possibility that BJP might change its stance and push for the creation of Gorkhaland sometime in the future. In 2009, Jaswant Singh of BJP became a Lok Sabha MP from Darjeeling and voiced his active support for Gorkhaland. The BJP’s support to the creation of Telangana as well as the Modi government’s demonstrated capability to take bold and swift decisions (on demonetization and the Goods and Services Tax, for example) has raised the possibility (and hopes) of a separate Gorkhaland. If the central government fails to take West Bengal on board regarding the Teesta agreement before Bangladeshi elections in 2019, the chances of the Teesta’s flow into Bengal being controlled by a center-backed Gorkhaland instead cannot be dismissed.

The discontent is more likely to keep bubbling without causing any significant changes in the political borders of the region for now. In the absence of a holistic and socially inclusive approach toward regional development however, such eruptions tend to be more frequent and intense. The Teesta River is the principal source of water for irrigation, hydropower, fisheries, navigation, and domestic water in the region, and hence it is not only logical but also imperative that the river be the central feature of the region’s plans for growth and development. At the state level, efficient use of Teesta waters to fulfill the developmental needs of North Bengal should be combined with restoring the river and maintaining environmental flows, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Adequate measures need to be taken to help the river and its riparians cope with the effects of climate change.

A healthy and efficiently utilized Teesta is vital for social and economic stability, and consequently, security in the region. Unless the concerns of the local communities – be they Gorkhas, Rajbanshis, or Bengalis – are addressed in a strategic, holistic, and empathetic manner, the discontent will continue to destabilize the Teesta basin.

Gauri Noolkar-Oak is a transboundary water conflicts researcher who has researched river basins in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. She is currently researching water conflicts in the Teesta basin as a JWHI Fellow with Both ENDS in The Netherlands.