Until recently, the success story of nuclear energy was considered a national pride of South Korea, as the country was not only able to establish a strong domestic nuclear market but also compete with other countries on the export front. However, the decision by the newly-elected president of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, to gradually phase out nuclear energy in South Korea has affected both the domestic and export prospects of the Korean nuclear industry. Such a policy, once implemented, will decimate South Korea’s hope for exporting nuclear technology by undermining credibility, capability, and opportunity.

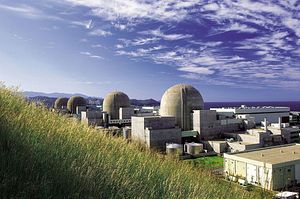

For the past two decades, the nuclear power program of South Korea has become a rare bright spot in the global nuclear industry. The country’s fleet of nuclear power plants has expanded threefold, from eight units in 1989 to 24 units by 2017 with on-time, within-budget constructions of advanced technologies like the APR1400 (Advanced Power Reactor with 1400 MW electricity capacity).

South Korean companies have also searched for opportunities abroad. In 2009, South Korea won its first nuclear contract abroad when the United Arab Emirates selected the consortium led by the Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) over more experienced bidders from France, the United States, and Japan to build four APR1400 units at Barakah. In the same year, the Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI) and Daewoo scored another win for South Korea in the nuclear export market when they secured a contract to supply the first research reactor for Jordan.

Then came the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan in March 2011, and the revelation in 2012 of several safety-related scandals of the Korean nuclear industry, like the cover-up of a station black-out incident at the Kori nuclear power plant, or the falsification of safety documents of plant components. In the aftermath, the Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) and Park Geun-hye (2013-2017) administrations reaffirmed the importance of nuclear energy by continuing the construction of three new APR1400 nuclear units, while reaching out to potential customers of South Korean nuclear technology by signing multiple nuclear cooperation agreements with countries like Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, or Czech Republic. The nuclear export ambitions of South Korea during this booming period were reflected through the the Ministry of Knowledge Economy’s optimistic 2010 plan to export 80 reactors by 2030. More modestly, in 2015, KEPCO projected six new contracts through 2020.

The good fortune of the South Korean nuclear industry has seemingly come to an end, however, under the new government of Moon Jae-in. In a move that stunned many domestic and foreign observers, Moon, citing safety reasons, announced his decision to phase out nuclear energy by suspending the ongoing construction of two APR1400 units, cancelling any domestic plans for new reactors, and gradually replacing all existing nuclear capacity with natural gas and renewable energy.

On the other hand, it appears that the Moon administration will continue its predecessors’ policy of promoting Korean nuclear technology abroad given the recent statement of South Korea’s new energy minister: “The problem we’re facing is having multiple units in a small country, and if other countries do not have such problems, I have no intention to stop exports at all and am planning to support such moves.” Despite such reassuring messages and other good news on the export front, like the smooth implementation of the Barakah project, Moon’s nuclear reversal will negatively affect South Korea’s nuclear export ambition in three aspects: credibility, capability, and opportunity.

In term of credibility, it is reasonable to argue that when the Korean president has openly stated that nuclear energy needs to be phased out for the sake of public safety, it will be very difficult to convince other countries to import the exact same kind of technology from South Korea. For comparison, when faced with public and foreign partner concerns about the safety of Korean nuclear technology following the Fukushima accident and domestic safety scandals, the Lee Myung-bak government implemented both internal reforms of safety regulation and external communications with the UAE on the nature of the scandals and the safety advantages of the APR1400 technology. These effective measures did help reassure the UAE, as the construction schedule of the four nuclear units at the Barakah site has been maintained without any major dispute.

In another example, the Japanese government, while admitting a faulty regulatory system for nuclear safety was one of the reasons that led to the disastrous events at Fukushima, still insists that the reactors that they offer to other countries are much more advanced, safety-wise, in comparison with the outdated ones installed at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant. In both cases, nuclear export opportunities were created and maintained, by emphasizing the safety features of the technology through continuous communication with foreign partners, and not by denouncing the same technology in front of the public.

In term of capability, experiences from the United States show that the lack of a robust domestic market will negatively affect the competitiveness of the country on the export front. Two decades without domestic orders for new reactors following the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in 1979 had a serious impact on the manufacturing and financial capabilities of American suppliers in their competition with vendors from other countries in new projects abroad. The latest sign of such struggles is the bankruptcy of Westinghouse, which was one of the two remaining reactor suppliers from the United States, in early 2017, and the decision by American utilities to stop the construction of two new reactors that were supposed to be the springboard for the revival of the American nuclear industry –both of which Westinghouse was primary contractor for.

In contrast, starting from an importer of nuclear technology, South Korea has recently been praised for a strong domestic industry that can independently design, manufacture, and build nuclear reactors with its own advanced technology. Currently, South Korea is also one of the few countries that can avoid significant delays in new reactor construction, largely thanks to accumulated experiences from continuously building new plants since the late 1980s. Korean companies will hardly be able to keep such a track record and reputation once Moon’s domestic phase-out policy is carried out, especially when new demands from other countries are few and far between and thus cannot help sustain the existing domestic manufacturing capacities of Korean suppliers like KEPCO and Doosan Heavy Industries.

Finally, the conflicting messages about phasing out the domestic nuclear fleet while promoting the same technology abroad will lower the chances for South Korea to win new contracts in nuclear newcomers like Egypt or Saudi Arabia. As previously mentioned, it was a big surprise in the international nuclear market when novice exporter KEPCO won the UAE project over experienced suppliers like Areva and EDF of France. One of the main reasons for such success is the strong coordination between the Korean government, KEPCO, and their partners in preparing for the UAE bid, whereas the French team consisting of Areva and EDF was actually stuck in an internal dispute during the same bidding period.

Lessons learned from this episode, and the strong performance of ROSATOM as the sole representative of Russian efforts in promoting nuclear technology abroad, have led to the creation of other national consortia in Japan (the International Nuclear Energy Development of Japan) and China (Hualong Company) to improve the chance of these countries in the international market. The nuclear reversal policy will likely create confusion between the South Korean government and nuclear companies; an early controversy has already been observed regarding the suspension of construction of two domestic reactors at the Shin Kori site. Under these circumstances, it’s an open question whether “team Korea” can keep its previously exemplary coordination in the race to win new exports faced with other strong contenders like Russia and China.

From the above discussion, a conclusion can be made that the nuclear export ambitions of South Korea will be severely affected once the nuclear phase out is official implemented by the Moon administration. Even if this policy is reversed by Moon’s successor, as the president of South Korea is limited to one five-year term, the damages in terms of credibility, capability, and opportunity to South Korea’s nuclear exports will be significant, especially when taking into account the declining interest in nuclear energy in once-potential customers in Southeast Asia. A policy that may have long-lasting repercussions domestically and abroad, like Moon’s nuclear reversal initiative, should be discussed thoroughly and democratically between all national stakeholders that may be affected in order to reflect a balance of interest for the common benefit of South Korea.

From a global perspective, the future of South Korea’s nuclear export capability is also of great interest. After the disintegration of the French nuclear giant Areva and the aforementioned downfall of Westinghouse, prospective customers will likely prefer a more competitive export market, with the strong presence of South Korea, to a rising duopoly between Russia and China.

Viet Phuong Nguyen is a Ph.D. candidate in nuclear engineering at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). He holds a B.Sc. in nuclear physics from the Vietnam National University and a M.Sc. in nuclear engineering from KAIST.