“Will you please see the cartoon in Dawn of 1 January? This is particularly offensive,” wrote Jawaharlal Nehru in 1947 to the Congress stalwart Sardar Patel.

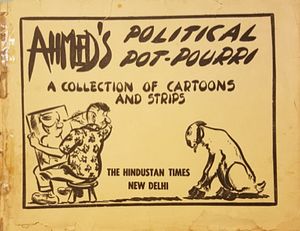

Gandhi the sorcerer, holding the “statement of December 5” trying to revive an ailing Congress. Ajmal’s cartoon in Dawn, “Try it!” offended Nehru. January 1, 1947.

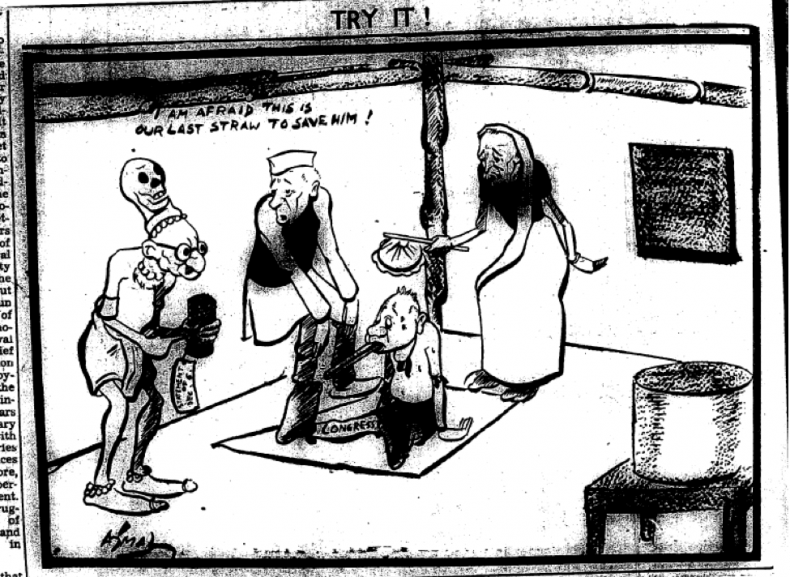

Continuing this correspondence on perspective and opinion, Lord Wavell, the governor general and viceroy of India (1943-1947), chimed in, cautioning Patel about Hindustan Times’s cartoons: “The Hindustan Times of 15 March, both in its cartoon and in the report from the Punjab, seems to me to contain matter which is actionable under the Press Ordinance. I realize the depth of feeling that has been aroused by these communal disturbances, but I think you should look into the question whether or not action should be taken against the Hindustan Times.”

“Good show, What!” The cartoon Lord Wavell objected to. The failure of negotiation and ensuing violence in Punjab in March 1947. Wavell checking time, Jinnah’s “no show,” and the “devil” Governor of Punjab, E. M. Jenkins, make this a scene of intrigue, double-crossing, and deceit. Ahmed’s cartoon for the Hindustan Times. March 15, 1947.

Patel agreed that the cartoon was “open to objection,” but questioned whether it fell within the purview of the ordinance, since it did not incite communal hatred: “It would be impossible to establish that the cartoon has this effect. It is no doubt a vulgar or mischievous cartoon, but if you have been reading the Dawn, you would find that even worse things have been appearing there; I enclose a cartoon which appeared some time ago. I am sure this cartoon does not suffer by comparison with the one to which you refer.”

As eyes turn to India and Pakistan this August on their 70th year of independence, I turn to an episode about cartoons in the Dawn and Hindustan Times — newspapers for two opposing political brands, the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. In August 1947, at the pinnacle of political deliberations and a violent slouch toward the independence of Pakistan (which then included Bangladesh) and India, the emerging nations’ leaders were nitpicking on offensive cartoons. The correspondence on vulgar and mischievous cartoons gives a glimpse of a fascinating struggle over intent, meaning and impact.

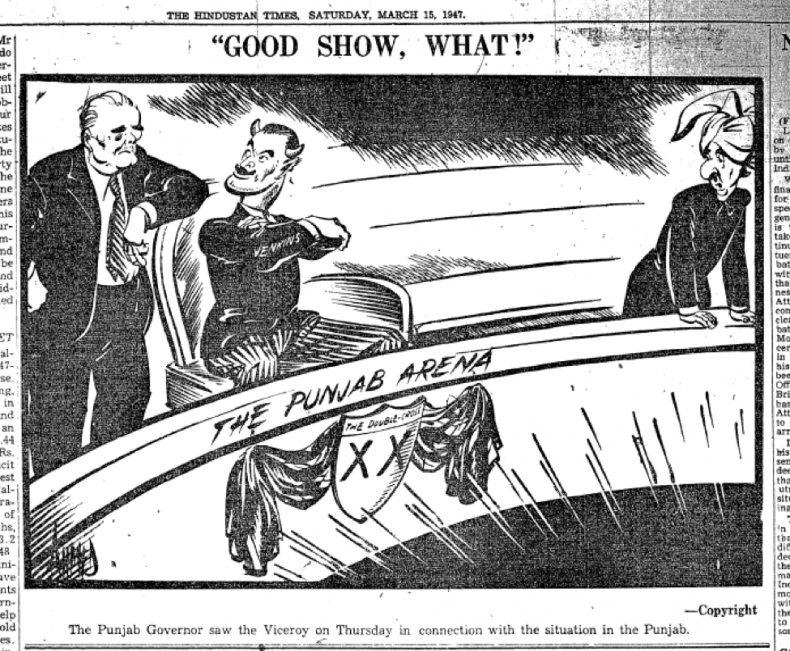

Ahmed’s disoriented and clueless Jinnah. Detail from a 1947 cartoon in the Hindustan Times.

Impropriety and offense were invoked, cartoon cuttings filed and exchanged, interpretations deliberated, feelings assessed and correspondence dispatched — all in the name of appropriate humor in grim times. The Press Ordinance codified the boundaries of what was permissible and prohibited in presses and publication. However, confirming intent to incite communal violence, the ethical border that was not to be crossed, was elusive. The point of incitement: imprecise. This “cartoon talk,” in the hectic months leading to the Partition, is a humbling reminder of the long history of the subcontinent’s cartoon debates and dilemmas. It leads us to that moment when Patel, Nehru, Wavell — politicians-as-interpreter — come alive to reveal a glimpse of the cartoon through their eyes.

The Dawn and Hindustan Times incident was not the first tug-of-war over cartoons. In colonial India, newspapers became a significant form of political communication as well as a perpetual thorn for the colonial bureaucracy. Politicians followed, scrutinized, and invoked cartoons to feel the pulse of politics, to sense the drift of public opinion, to see themselves and eye each other through the cartoonist’s brush. Writing from Allahabad in 1931, Nehru informed Bapu — his form of addressing Gandhi — that he had begun a regular subscription to the British Punch: “There was a lovely cartoon in Punch the other day about the ‘Elusive Mahatma’ – I wonder if you saw it. I was so taken by it that I forthwith subscribed to Punch as well as other English newspapers to read what they say about you.” In 1941, in a letter to his companion, personal physician, and fellow Congress activist, Sushila Nayyar, Gandhi enclosed a set of cartoons that he thought she might enjoy. The colonial years leading up to 1947 was a busy world for cartoons.

The Dawn cartoons that perturbed Nehru and Patel were by Ajmal Husain (1926-2015). The Hindustan Times cartoon that Wavell considered actionable under the Press Ordinance, were by Enver Ahmed (1909-1992).

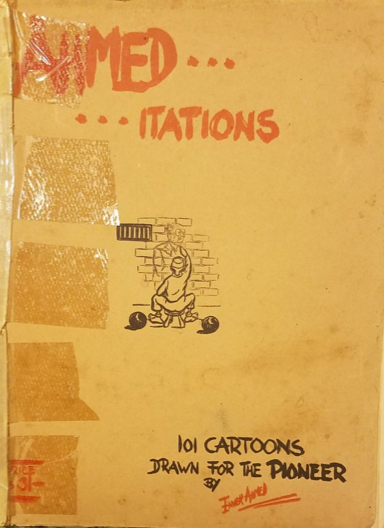

Ahmed’s career took him to newspapers of divergent political ideologies: The Pioneer, Dawn, and the Hindustan Times.

Cartoons were serious business; yet their effect was incalculable. Patel, Nehru, and Wavell’s speculation about cartoons adds a new twist to “cartoon talk.” Due to the bloodshed that soon became a nightmare for the two new nations, the press was legally bound not to publish reports that would incite hatred and violence. The ambiguity about cartoons as incitement for unrest and communal violence was pitched against the certitude of prose. They were less tolerant of disturbing prose. Nehru and Patel resorted to legalese to stave off Wavell’s objections and acquitted Ahmed’s cartoon.

Long before the Dawn–Hindustan Times rivalry, vernacular Punch newspaper editors in colonial India were intrigued by the double standards of British cartoon humor. They critiqued such imperial hypocrisy: “The truth is that we are condemned for writing what we had learnt from our tutors” (Khanduri). Criticism was not reserved for the British. Gaganendranth Tagore’s first cartoon album Birupa Bajra (Strange Thunderbolts, 1917) received public opprobrium (Sunderason). Reflecting on Tagore’s biting caricatures, the scientist J. C. Bose noted, that such satirical pictures must have “wronged the artist’s soul with sorrow” (Mulk Raj Anand, Parimoo).

Readers wrote letters to editors. A “decent citizen,” protested Amrita Bazar Patrika’s cartoon in 1947 that depicted the Muslim League leader, and future Quaid-e-Azam of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah as a shoe-shine boy (Kamra). To evidence its impropriety, denouncement by peer-newspapers would result in impassioned defenses and even republishing the offensive cartoon. Such public airing of disapproval gave a new lease of life to the cartoons. There was a price to pay in silence and in speech.

Gandhi had a long arc in the cartoon world: He was its object, subject, fan, and critic. He was adept at decoding cartoons and confirming their propriety and intent. One sees his interpretive authority in his columns in the Indian Opinion, published from South Africa, in his reprimand of cartoonist Shankar Pillai, the apple of Jawaharlal Nehru’s eye, and in his debate with Rajkumari Amrit Kaur. Gandhi was convinced about the power of cartoons. For Gandhi, cartoons provided a window to the mind of colonial rulers; they revealed the cracks in any semblance of a colonial consensus about their right to rule. For Gandhi, cartoons could also injure through impropriety and factual inaccuracy leading, for example, to Shankar’s inelegant depictions of Jinnah. Gandhi’s reminder about mindfulness in cartoons was not consistent, however. He dismissed Rajkumari Amrit Kaur’s objections to Shankar’s misogynist portrayal of educated women.

In 1947, Ajmal’s Gandhi the sorcerer and Ahmed’s devilish colonial bureaucrat and a delinquent Jinnah were at the center of deliberations among Patel, Nehru, and Wavell. These newspaper cartoons perplexed them, as the politicians were unable to discern their vulgarity or to forecast the impact of such images on public emotions. In these cartoons and more, Ajmal, Ahmed, and their peers scrubbed away the leaders’ respectable sheen, revealing them as brothel madams, nautch girls, fascists, lovelorn Gopis, disoriented and opportunistic individuals. The devil was in these details. One might speculate that by taking turns in escalating their degree of vulgarity and mischief, the cartoonists gleefully raveled Jinnah, Khan, Nehru, Patel, and Wavell.

There was no evidence linking the cartoon to public violence. Yet in the minds of these politicians a dark cloud of suspicion hung over newspaper cartoons. With no exact measure for cartoon impropriety, except by comparison with rival newspapers’ cartoons, there was much back and forth of correspondence. For Patel, the Hindustan Times cartoons seemed less vulgar and mischievous when compared to the Dawn cartoons. The offense was one of degree. This shadow of doubt made vulgar and mischievous cartoons pardonable and permissible.

Ritu Gairola Khanduri is the author of Caricaturing culture in India: Cartoons and history in the modern world. She is a cultural anthropologist and historian of India with interests in media, material culture, and Gandhi.