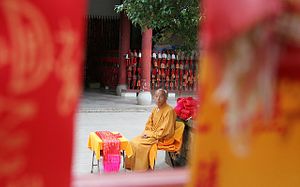

For centuries Yunnan has served as China’s gateway to Southeast Asia. Besides trade, an important component of this linkage is the exchange of religion and religious groups, in this case Theravada Buddhism. Since its 7th century arrival in Yunnan via Myanmar, Theravada Buddhism has retained a position of deep influence among the Dai, Blang, and Palaung nationalities of the region.

Today, Theravada Buddhism remains a significant cultural linkage between China and Southeast Asia. Countries with the most Theravada Buddhists — Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia — also happen to be key states on China’s land and maritime silk road initiative. Cultivating ties with Theravada Buddhist countries therefore makes sense in projecting a warmer and softer image of China, in addition to allowing China access to powerful members of the sangha that are not only venerated community leaders, but also in some instances policy advisors to high decision-makers.

But the general limits of Chinese Theravada Buddhism seriously undercut any soft power initiative overseas.

To begin with, Theravada is the smallest school of Buddhism in China. Compared to Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism, which have millions of followers across large swaths of the country, Theravada Buddhism’s influence is confined to border regions near Myanmar and Laos.

Moreover, Theravada Buddhism suffered terribly after the arrival of communism. In the name of anti-feudalism, temples, pagodas, and Buddha statues were damaged or outright destroyed. Monks were defrocked and persecuted, while all Buddhist activities were banned.

Although state-led oppression started in the late 1950s, these measures reached a climax during the Cultural Revolution. Precious palm-leaf manuscripts were burned to ashes. Everywhere in the Theravada country stood abandoned temples and ruined pagodas. The Xishuangbanna General Buddhist Temple, China’s largest Theravada temple founded in the 8th century, was totally destroyed.

Like all other faiths, Theravada Buddhism experienced a revival after the perilous Cultural Revolution years. But this revitalization came slowly. While the rebuilding of Buddhist temples was allowed again, local governments refused to return temple-owned lands confiscated during the Mao years. Although monks can study the scriptures again, they were placed under the close watch of local state religious affairs administrations, which control all activities within the monkhood.

At present, Theravada Buddhism in China is in a state of stagnation when compared to the flourishing developments in neighboring countries. For one, there is a severe shortage of monks. There is only one monk available for every two of Yunnan’s Theravada temples. Due to the shortage, many temples had to shut their gates to worshipers except during major Buddhist holidays. The phenomenon of “empty temples” is quite haunting. 18.8 percent of Xishuangbanna Prefecture’s temples stand empty. In Pu’er and Lincang it is about 40 percent. While in Dehong Prefecture, the number jumps to 90.1 percent, and in Mang City, 98.2 percent.

Foreign monks from Myanmar and Laos are often invited to Yunnan temples in order to fulfill the shortage. However, the government views these outsiders with distrust because of their lack of political reliability. Trained outside China, foreign monks are not filtered through the rigid political indoctrination system that requires all monks to voice support for the supremacy of the Chinese Communist Party, commitment to the socialist path, national unity, and ethnic harmony. The party expects monks to serve as propagandists, while foreign monks have little to no conception regarding this matter.

Besides the political factors and the shortage of monks, the lack of official funding and quality Buddhist schools are also a problem.

Every year, the state allocates billions in renovating Tibetan Buddhist temples and educating Tibetan clerics. The same cannot be said for Theravada Buddhism. Unlike the rebellious Tibetans, ethnic followers of Theravada Buddhism are considered China’s “model minorities.” Despite cultural differences between, say, the Dai and the Han, the former never agitated for secession. Even with ethnic kinsmen across the border, the Dai never showed any intention to break away. While this creates fewer problems for the state, it brings in less money for Theravada temples, as opposed to official attempts to buy Tibetan support through patronizing Tibetan Buddhism.

There are only three schools in China that offer Theravada education. But they all suffer from funding issues. In addition, the quality of education is inferior compared to major Theravada institutions in Thailand, for example. In fact, it is the dream of many young novices to complete their higher education at one of Thailand’s world-class Buddhist universities, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University or Mahamakut Buddhist University. There have been talks of building China’s first advanced-level Pali-language school in Yunnan since 2012, but nothing has come about except the purchase of a plot of land.

In short, Chinese Theravada Buddhism is in no position to serve as a soft power agent given its underdevelopment. State policies show that government bureaucrats probably never even recognized the value of Theravada Buddhism in benefiting China’s relations with the outside world. Public diplomacy does not work in a system where monks must get official approval for everything, be it travelling overseas or hosting a simple religious event while abroad. Sadly, Chinese Theravada Buddhism has always been on the periphery of the Theravada world, and it looks like it will stay there for the foreseeable future.

Zi Yang is a researcher and consultant on China affairs. He covers Chinese politics, security, and emerging markets. Zi holds a M.A. from Georgetown University and a B.A. from George Mason University. Follow him on Twitter @MrZiYang.