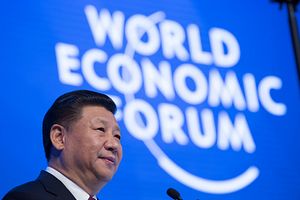

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s long-running campaign to promote Chinese culture and history domestically and abroad has a new objective: deciding what constitutes “world heritage,” and what doesn’t, at the helm of UNESCO. With elections to head the Paris-based body coming up in October, Beijing is lobbying hard for its nominee, Qian Tang, to win the race and become the organization’s next Director General.

Gunning for UNESCO falls neatly within Beijing’s “great-power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics,” as Xi so aptly put it in 2014. Beijing has become highly adept at the kind of international lobbying needed to win a nod from the storied cultural organization, and is on track to surpass Italy and become the top-ranking place of cultural heritage sites. With several dozen Chinese sites slated for consideration for World Heritage status and with the possibility of increasing tourism revenues by billions in years to come, the stakes are higher than ever.

But is this what UNESCO needs? Indeed, the organization is going through an identity crisis, riven by debates between certain members over controversial issues. Last October, for instance, Japan temporarily withheld its 2016 funding from UNESCO following the organization’s decision to include documents about the Nanjing Massacre of 1937 in a memorial program. Tokyo had called into question the authenticity of certain documents about the massacre submitted by Chinese organizations for inclusion in the program, drawing a sharp rebuke from Beijing. On top of that, of course, the Israel-Palestinian conflict continues to divide key member states, with Israel most recently denouncing UNESCO’s recognition of the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron as an endangered site.

Such political games have sidetracked the organization’s original purpose: protecting world heritage sites, promoting collaboration among member states through education, science, culture, and defending freedom of expression. Dovetailed by budget cuts and a bungling leadership that is accused of encouraging tourism and accelerating the destruction of fragile landmarks, UNESCO is an increasingly rudderless organization. According to a major report released earlier this year, more natural World Heritage sites are under threat than ever before – with the biggest increases occurring in China and neighboring Asian countries. Sites singled out as among the most threatened include China’s storied Mount Taishan and Mount Wuyi, which are threatened by increased tourism and pollution.

The 72-year-old agency has only had a total of 10 director generals in its history. This means that whoever takes the helm in October will have a critical chance – and perhaps the last one – to steer UNESCO back to its original mission of protecting cultural and natural wonders, and to prevent member states from trying to turn heritage sites into notches on their belt.

But if for Beijing getting Tang ordained as head of UNESCO would be a new status symbol for a government collecting them like poker chips, it would nevertheless represent a step in the wrong direction for the organization. Tang is not quite the revitalizing force UNESCO needs, as he has been part of the body since the early 1990s, and currently occupies the job of Assistant-Director General for Education. Compounding Tang’s old guard image is the way China has commodified heritage sites, sparking fears that Beijing’s bid for UNESCO would do little to improve the status of such monuments. While China has used tourism for regional development, few thoughts were spared for the protection of the site itself.

The recent example of Chikan is telling: after the city’s diaolous (fortified, multi-story buildings) were put on UNESCO’s list, the government decided to evict 4,000 households from their vicinity and make space for more tourist attractions. The Kaiping city government took out a $900 million loan and will start redeveloping the area, with the ultimate aim of increasing the number of arrivals from the current level of 6 million to 7 million by 2020. Or take the Mogao Grottoes, where moisture from visitors’ breath harmed the cave paintings and fragile Buddhist sculptures contained within. The number of tourists visiting the site has jumped 20-fold in the past two decades.

This is bad news for UNESCO, as the body’s new director general will play a key role in crafting a more robust framework for promoting sustainable development in historic locations – and to push member states to do the same. But unlike the approach being championed by China, the agency must encourage governments to take a more holistic approach to world heritage sites, balancing conservation and commercial needs.

Of course, UNESCO has spoken in favor of sustainable tourism in the past and has even designated 2017 the “International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development.” But so far, this idea is still more theoretical than practical. According to Clement Liang, a member of the Penang Heritage Trust, “Currently UNESCO has no clear guidelines or effective methods to control the commercialization of world heritage sites, and its talk on sustainability is more a verbal exercise than enforceable.”

Luckily, it’s far from certain whether China will land the top UNESCO spot. Running neck and neck with Tang is France’s candidate and former culture minister, Audrey Azoulay. A young civil servant with no ties to the current UNESCO management, her bid is supported by France’s Emmanuel Macron and carries none of the political baggage Tang has. She has spoken against the politicization of the organization and has proposed using the Paris body to counter radicalization through the promotion of education. Another contender is Egypt’s former family and population minister Moushira Khattab – although Cairo’s dismal human rights record has not earned her much support.

Given this state of affairs, UNESCO requires a deep rethink. Given China’s rich history and desire to take a more active role in global affairs, there is a compelling argument for Tang’s candidacy. But with the organization still riven by discord, and with more heritage sites than ever before at risk of becoming victims of their own success, the world needs a director general who will make sure that the race for cultural acclaim doesn’t become a race to the bottom.

Grace Guo is a Vienna-based researcher and a program associate for a small NGO focused on Asian politics.