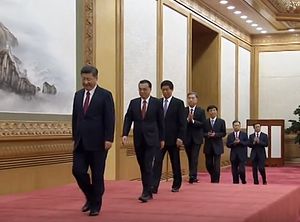

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) finally revealed its new generation of top leaders — the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). The PSC will run the country as the CCP’s highest decision-making body in the next five years until the 20th Party Congress, and the next round of leadership reshuffling.

After reams of speculation over the past years, reality has finally emerged from the “black box” of CCP elite politics. Aside from Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, who still remain in the PSC, the other five PSC members are new faces, some more familiar to analysts than others.

The following will present a brief introduction of the five new faces according to their political rankings, which is consistent with their line-up order at the introductory press conference.

Li Zhanshu

Li, 67, the current director of the General Office of the CCP, has been referred by some western media as “chief of staff” for Xi. His role is actually more than that: Besides overseeing the routine administrative affairs of the CCP’s Central Committee and the PSC, he manages the top secrets of the nation as well as of all the top leaders.

Li is also a longtime friend of Xi. As early as the 1980s, Li reportedly worked with Xi in the same area in Hebei province. Like Xi, Li is the descendant of prominent senior communist officials. Li has close personal relations with Xi’s family as well.

In 2012, Li was promoted to his current position, replacing Ling Jihua, who was sentenced to life imprisonment under Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. Li also holds the position of chief of the General Office of the Central National Security Commission (CNSC) — set up by Xi in 2013 as the highest organ that oversees national security.

Wang Yang

Wang, 62, one of the four vice premiers under Li Keqiang, is considered by observers at home and abroad as a liberal-minded official in China’s top leadership.

From 2007 to 2012, he served as the top leader of Guangdong province. Under his office, civil society tended to have some space to develop in Guangdong, compared to other regions in China. Several liberal newspapers in China at the time — Southern Weekly, for example — were able to survive during Wang’s tenure. He openly called for political and economic reform as well.

It was rumored that he could become a member of the PSC at the 18th Party Congress in 2012, but he reportedly failed at the end, faced with strong opposition from another faction within the party. Wang is affiliated with the Communist Youth League, which has ties to former CCP leader Hu Jintao.

Wang Huning

Wang Huning, 62, is the CCP’s top political theorist and major policy advisor for Xi.

Born in Shanghai and graduated from a prominent Chinese university with a major in international politics, he became the youngest dean in his college in his late 30s. In his forties, Wang was summoned by then-President Jiang Zemin to Beijing as head of political group in the Research Office. Since then, he has served as a key adviser to three successive presidents: Jiang Zemin, his successor Hu Jintao, and now Xi.

Wang is believed to be the key initiator and designer of every political campaigns issued by these three successive presidents, from Jiang’s “Three Represents,” to Hu’s “harmonious society” and “scientific development,” and to Xi’s “China Dream” and “One Belt One Road Initiative.” He will oversee China’s ideological organs now that he has entered the PSC.

Although he controls the mind of the state, he has kept his own mind extremely private. The only track record of his personal ideas comes from academic books and journals published in his early years.

Zhao Leji

Zhao, 60, the head of the CCP’s Organization Department, manages the human resource within the party.

Like Li and Xi, Zhao reportedly was born to a family of senior communist officials in Qinghai province. Although the details of his family tree are not public, the fact that he was able to get enrolled into Peking University — one of the most prominent universities in China — in 1977, ahead of the end of the Cultural Revolution when the national college exam was resumed, indicates his “red” background.

What came as something of a surprise is that he has been appointed to replace Wang Qishan to run the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) — the CCP’s highest internal-control institution. CCDI has been in charge of the grand anti-corruption campaign under Xi since 2012. Ahead of the Congress, there was much speculation that Wang Qishan would remain on the PSC, despite being past the traditional retirement age, to continue his work with the CCDI. Instead, Zhao has assumed that mantle.

His experience in the CCP’s Organization Department should help him perform well in his future position, as he has already in good knowledge of the background of all high officials across the country.

Han Zheng

Han, 63, is the least well-known figure among the five new faces.

Han’s resume looks considerably plain: Born and raised in Shanghai, he has spent his entire career in Shanghai, too. From 2003 to 2012, he served as mayor of Shanghai; in late 2012, he was promoted to the party secretary of Shanghai.

Yet the fact that he was able to hold his position in Shanghai for such a long time is also what’s most remarkable of him. Shanghai is a city known for hidden political struggles among different factions within the party. Shanghai is also known as the headquarters of the “Shanghai clique,” or the clique surrounding Jiang Zemin.

Han not only survived the political purge after Chen Liangyu’s removal (Chen was removed as party secretary of Shanghai in 2006 and sentenced to 18 years in prison on charges of financial fraud, abuse of power, and bribery) but also worked under Xi for a short period when Xi was “parachuted” into Shanghai after Chen’s purge. The short but important period of working together could have won Xi’s trust for Han.