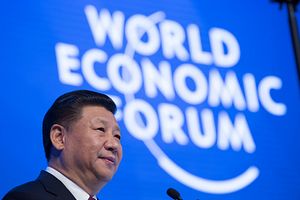

Chinese President Xi Jinping has used China’s 19th National Congress not just to anoint himself the Great Helmsman but also to firmly enshrine environmental protection in the country’s development path.

The resolution of the CCP’s Central Committee report, published at the end of the Congress, specifically seeks to “promote green development, solve prominent environmental problems” and “work to develop a new model of modernization with humans developing in harmony with nature.” While this might sound like vacuous newspeak, the sad fact of the matter is that in the absence of U.S. leadership, Beijing’s policies are likely to set the global agenda.

All year long, Xi has been scoring points with the international community almost exclusively through discursive acts, namely showing up and saying the right things. As a vocal defender of the Paris Climate Agreement, Xi secured more supporters after he chastised Trump for withdrawing the United States from the accord. One week after the American withdrawal, Beijing hosted a high-level international forum for energy ministers. During the meeting, Chinese energy officials assured that China’s Paris Agreement targets would be met on, or before, the target date and delivered a presentation on the value of clean renewable energy sources over coal or natural gas.

Not only was Xi able to promote his support for global cooperation on environmental issues unabatedly; it also helped to position himself as the international community’s counterweight to Trump’s brash and toxic brand of leadership. China – the largest energy consumer and the world’s biggest polluter – has rebranded itself as the global steward of green initiatives.

While the United States relaxes restrictions on coal-fired power generation, China is betting big on the long-term benefits of solar power. After doubling the number of solar panels in 2016, China’s overall solar power capacity is now twice as large as that of the United States. In southern China, decommissioned coal mines are turned into solar farms. Meanwhile, in Anhui province, an enormous floating solar power installation was built atop a lake created by an abandoned mine.

Since 2014, the country has slashed its coal usage and dramatically reduced its carbon footprint. China’s CO2 emissions for 2017 will mark the fourth consecutive year of declining emissions. But China’s new role is also represented by the fact that Xi is not afraid to spend serious money on making “Green China” a long-term reality. China’s National Energy Agency (NEA) pledged a 2.5 trillion-yuan ($361 billion) investment into clean energy generation. While such investments are impressive, they also speak to mounting public pressures on the CCP leadership to transition to renewable technologies and enact more robust environmental regulations.

Further American action could strengthen China’s leadership position on climate change issues. By openly condemning the renewable energy sector and promising support for the coal industry, the Trump administration laid bare the stark divide between Washington and Beijing’s environmental stances. This rhetoric is dovetailed by fears that Trump will impose tariffs on Chinese solar cell batteries – a move that would devastate the United States’ solar panel industry, driving up consumer prices to unaffordable levels, threatening more than 16,000 jobs, and capping America’s carbon emission reductions at their current level.

Still, for all of its bravado in the face of Trump’s actions, the decision to fill the void in global environmental leadership put Beijing in a tight spot. Prematurely hailed as the global standard-bearer for climate actions, China suffers from a highly fractured power sector that remains a serious internal challenge to its de-carbonization plans. The sector is dominated by powerful coal-dependent heavy industries, particularly steel and aluminum producers, which continue to lobby for slowing down China’s climate actions.

Their ability to influence decision-making was laid bare when Beijing approved the construction of more than 100 new coal-fired power plants, despite falling coal use and mounting non-fossil capacities. Since coal is relatively cheap, it has enabled Chinese metal producers to maintain an edge over foreign competitors and has directly contributed to surging overcapacity in the production of steel and aluminum.

Plans to restructure the economy based on phasing out inefficient heavy industrial producers have been advancing slowly, severely threatening to derail China’s leadership ambitions. Heavy industries worldwide are changing tack under environmental pressures and are increasingly moving away from coal to renewables to cover their power requirements. Major metal companies, like Rusal and Norsk Hydro, have been big advocates of sustainably produced aluminum and make use of clean hydropower instead of coal to power the smelting process. By investing in cleaner energy and technologies, China’s heavy industry sector can contribute to reining in pollution and tackling the country’s overcapacity problems.

As consumers worldwide become much more climate conscious, it is essential for China, if it really wants to rein in the global economy, to bring down the environmental burden of its products from the beginning of the production phase. Otherwise, Chinese producers will be unable to compete with the less polluting aluminum producers in the long-run, including Rio Tinto, Rusal, Norsk Hydro and Alcoa – all of which emit significantly lower levels of CO2 per ton of aluminum, but have suffered due to Chinese overproduction.

But failure to act by Chinese firms means the current issue of overcapacity will continue to draw the ire of the West and those companies hit hardest. For example, the Trump administration has proposed invoking the rarely used clause Section 262 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which would allow the Department of Commerce to impose a global ban on the imports of steel and aluminum for national security reasons. Such a policy would only serve to further curtail America’s access to crucial imports – be they from China, Russia or elsewhere – and deal a deathblow to Washington’s credibility to lead.

And therein lies the rub – with Washington operating with probably the narrowest definition in history of what constitutes “national interest,” the world is losing the one country that managed to push Beijing into caring about climate change. Indeed, Beijing likes to breeze over the fact that the Paris Agreement was saved by a last-minute push to get India and China on board and continues to finance the construction of coal plants abroad. And without the United States to keep Xi in check, could the Great Helmsman take advantage of his newfound position to backtrack on those pledges?

Chris Zhang, originally from China, now works as a New York-based sustainability adviser. He studied international affairs at Fudan University in Shanghai and is a keen observer of political corruption and environmental standards in China.