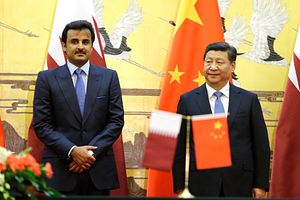

On September 27, 2017, Qatari Major General Saad Bin Jassim Al Khulaifi and Chinese Minister of Public Security Guo Shengkun met at the INTERPOL summit in Beijing to discuss counterterrorism cooperation. After the summit, both ministers signed a deal that formalized joint efforts between Doha and Beijing to curb funding to terrorist groups, and increased Qatar-China coordination against terrorism in the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific region.

Even though Doha-Beijing ties have strengthened considerably in recent years, the timing of China’s counterterrorism deal with Qatar is intriguing, as Beijing has recently expanded its security links with Qatar’s principal strategic rivals, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). China’s decision to upgrade its security partnership with Qatar during a period of turmoil in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) can be explained by four strategic factors.

First, China views Qatar as a lucrative destination for military technology exports. China’s decision to sell military technology to Qatar was underscored by Beijing’s active participation in the 2014 Doha International Maritime Defense Exhibition, which resulted in Qatar’s purchases of $23.89 billion worth of weaponry from various defense partners. Even though Qatar did not purchase any of China’s missile systems, Chinese ambassador to Qatar Gao Youzhen openly called for an expansion of trade links between Beijing and Doha after the exhibition.

As China is a major importer of Qatari liquefied natural gas (LNG), Beijing is keen to improve its balance of trade with Doha through military technology sales. The United States’ recent efforts to challenge Qatar’s position as a leading LNG exporter to China could convince Doha to acquiesce to Chinese pressure and deepen its military links with Beijing in hopes of out-competing American LNG.

In particular, Qatar could purchase stealth weaponry from China to neutralize the impact of Beijing’s March 2017 establishment of a drone manufacturing company in Saudi Arabia. As many countries have criticized Qatar’s shipments of weaponry to Islamist opposition forces in Libya and Syria, China’s non-interventionist approach to arms sales makes it an attractive security partner for Qatar during a period of unprecedented economic isolation.

Second, China possesses normative solidarity with Qatar in the security sphere, as Qatar is the Arab country that is most willing to negotiate with Islamist non-state actors without preconditions. As China believes that promoting all-inclusive diplomatic dialogue helps resolve international security crises, Beijing views Qatar as a highly useful partner in the Arab world.

The synergy between China and Qatar on diplomatic norms is evident in both countries’ responses to the crises in Palestine and Afghanistan. Since the election of Hamas in the Gaza Strip in 2006, China has refused to label the group as a terrorist organization and described Hamas as a legal entity that can legitimately represent the Palestinian people.

Qatar has embraced a similar position on Hamas. Since the mid-2000s, Qatar has insisted that its aid to the Palestinian organization is aimed at improving socioeconomic conditions in the Gaza Strip and that Doha does not endorse the violent objectives of Hamas’s military wing. China’s efforts to promote an all-inclusive settlement to the Israel-Palestine conflict will benefit greatly from Qatar’s assistance, as Qatar possesses considerable influence in the Palestinian territories.

The synergy between Qatar and China’s position on Palestine is mirrored by similarities between Beijing and Doha’s approaches to Afghanistan. In recent years, China has emerged as a leading advocate of a political settlement between the Afghan government and Taliban, and has held diplomatic dialogues with both major factions in the conflict.

Therefore, Chinese officials viewed the establishment of a Taliban office in Doha in 2013 as a positive development. China’s support for the legitimacy of Qatar’s Taliban office was underscored by the visit of Abbas Stanikzai, the head of Doha’s Taliban office, to Beijing in August 2015. These actions explain China’s tacit support for Qatar’s decision to keep its Taliban office open, in spite of rising international pressure, and Beijing’s rejection of Saudi allegations that Qatar’s Taliban links are a form of state-sponsored terrorism.

Third, the Chinese government believes that enhancing counterterrorism cooperation with Qatar will cause Doha to prevent its Islamist allies from threatening the security of China’s Muslim majority Xinjiang province. Even though Qatar has not been directly linked to Islamic extremist elements in Xinjiang, Beijing is circumspect about Doha’s links with Sunni Islamist movements in Syria and Iraq, as Uyghur forces have fought alongside Qatar-aligned factions in these conflicts.

If Qatar can reassure China that its activities will not cause violent unrest among Xinjiang’s Uyghur population, China will be able to cooperate with Qatar on security issues with little risk of backlash. Even though China had previously expressed concerns about Qatar’s links to Islamist movements during the Arab Spring, Beijing’s non-interventionist position during the Arab uprisings ensures that China can tolerate Qatar’s Islamic extremist connections in the Arab world with a greater degree of impunity than other great powers.

Fourth, China’s strengthened security partnership with Qatar bolsters its case to act as a mediator in the rapidly intensifying GCC security crisis. China’s official commitment to supporting the cohesion of the GCC has been a central tenet of Beijing’s Middle East strategy since Wen Jiabao’s 2012 visit to Qatar.

While China’s normative desire to preserve the GCC’s cohesion has contributed to its cautious approach to the Qatar crisis, Beijing’s interest in a peaceful resolution to the Saudi Arabia-Qatar standoff is also motivated by economic considerations. As China’s One Belt, One Road vision includes the promotion of trade across the Arabian Peninsula, instability in the GCC is a highly concerning prospect for Beijing.

Even though China has insisted that regional actors should resolve the Saudi Arabia-Qatar dispute, Beijing could attempt to facilitate dialogue between the two countries by emphasizing their shared interest in economic development and highlighting the pernicious implications of a long-term GCC schism on regional stability. While the dynamics of the Qatar crisis are unlikely to change drastically as a result of Chinese mediation, Beijing’s close relations with Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE give it exceptional arbitration leverage in a region marred by extensive polarization.

While China’s economic and security links with Qatar remain significantly smaller than those with Saudi Arabia, Beijing’s decision to strengthen its security links with Doha can be explained by normative synergies, threat containment desires, and China’s growing interest in extra-regional diplomacy. The rapid intensification of strains within the GCC will severely test China’s neutral position on the Qatar crisis, but it is likely that Beijing will continue to balance between Qatar and Saudi Arabia in the months to come.

Samuel Ramani is a DPhil candidate in International Relations at St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford. He is also a journalist who contributes regularly to the Washington Post and Huffington Post. He can be followed on Twitter at samramani2 and on Facebook at Samuel Ramani.