The next year, 2018, will be a special one for Singapore’s engagement in ASEAN. The city-state has taken over the chairmanship of ASEAN from the Philippines. At the same time, Singapore is acting as country coordinator of ASEAN-China relations until the end of 2018.

To some extent, assuming such important roles at the same time is a tough task for Singapore. It has to represent and lead ASEAN to engage China, especially on the thorny South China Sea (SCS) issue. But this is also a strategic opportunity for Singapore to showcase its statecraft, further bolstering its national reputation, strength, and influence if the city-state can make significant contributions to fostering ASEAN-China cooperation on the matter. Here are five recommendations for Singapore as it takes over the ASEAN chair.

Further ASEAN’s Interests

First, while seeking the sound development of bilateral ties with China, Singapore must focus on enhancing the interests of ASEAN. Singapore has made considerable efforts to reassure China that it is acting as a scrupulously honest broker, rather than taking sides with the United States or ASEAN in the SCS disputes. To that end, Singapore downplayed the SCS issue in its interactions with Washington and within ASEAN.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s visit to the United States in October 2017 went soft on the SCS issue. The joint statement of the visit did not mention the “militarization of outposts,” which was a key phrase included after his 2016 visit. Also, Singapore neglected to push the SCS issue at ASEAN meetings, allegedly exacerbating the division within the bloc.

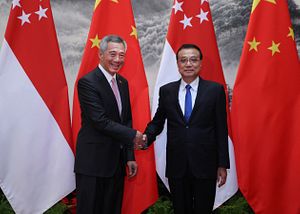

To some extent, these moves help Singapore restore mutual trust with China, with Lee confirming their relations are “on track.” However, Singapore should be aware that enhancing the interests of ASEAN is a statutory obligation of both the ASEAN chair and the country coordinator of relations with dialogue partners, as stipulated in ASEAN Charter. Articles 31-32 provide that any member state holding the ASEAN chair has to “actively promote and enhance the interests and well-being of ASEAN” and “ensure the centrality of ASEAN.” Meanwhile, Article 42 states that a country coordinator has to “coordinat[e] and promot[e] the interests of ASEAN in its relations with the relevant Dialogue Partners… [and] represent ASEAN and enhance relations on the basis of mutual respect and equality.”

Put the SCS on the Agenda

Second, and accordingly, Singapore has to place the SCS on top of the ASEAN-led fora’s agenda, particularly the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting (AMM), ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS), ASEAN Defense Minister Meeting (ADMM) and ADMM-Plus. The reason is simply that these multilateral fora play an important role in reinforcing international law and practice and building practical cooperation among member states. At these gatherings, ASEAN member countries, together with China and other relevant countries, have an opportunity to exchange views, create a better understanding, build more trust, and introduce innovative initiatives to effectively co-manage the tensions in the SCS, and build a good order at sea for peace, security, stability, and prosperity in the region.

In addition, Singapore can ensure that the SCS-related language in ASEAN meetings’ final documents is both unanimous and strong enough to promote the building of a united, coherent, and self-reliant ASEAN. There are two options to achieve this end. First, Singapore can take the lead to employ strong words and phrases that imply Chinese assertive actions in the SCS, then wield its influence to forge a consensus within the association. In this case, Singapore must be strong enough to withstand China’s pressure (drawing lessons from the seizure of Terrex armored vehicles and the Belt and Road Forum spat). Second, Singapore could consider applying the SCS formula devised in the AMM-50 joint communiqué, which perfectly matched the real case in the SCS. This way is safer and more efficient, since ASEAN meetings are inheritable.

Prioritize a Legally-Binding Code of Conduct

Third, Singapore should prioritize the formulation of an effective and legally binding Code of Conduct (COC). ASEAN and China have adopted a Draft Framework, providing the basis for subsequent negotiations on a COC. As scheduled, the leaders of ASEAN member states and China, at their 20th Summit in Manila, announced that negotiations would officially commence. The Senior Official’s Meeting and Joint Working Group on the Implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct were entrusted with drafting the text.

Unquestionably, these developments create positive momentum toward the conclusion of a long-delayed COC. But we need not hold high expectation on this, because it is impossible to finish the COC overnight. What Singapore and ASEAN member states should do is to design an effective and legally binding COC. Professor Carlyle Thayer has given useful insight on this. He suggested that the code must include: “(1) a precise definition of the geographical scope of coverage; it could take the definition of the SCS by the International Hydrographic Organization for example (from north of Taiwan to the entrance to the Straits of Malacca etc.), (2) mechanisms to resolve differences of interpretation of the COC, (3) a binding and enforceable dispute settlement mechanism, and (4) was legally binding through ratification by national legislatures and deposited with the United Nations.” Among these, the COC being “legally binding” must be heavily emphasized, and this point must be determined as early as possible in order to set the direction for subsequent negotiations.

Moreover, the COC must be negotiated as part of the ASEAN-China process, not an 11-party process (meaning the 10 ASEAN member states and China). Recent research on ASEAN’s external relations shows that 62 percent of documents between ASEAN and its dialogue partners have been signed in this way over the last 50 years. Reasonably, ASEAN can engage China on the COC as a sole legal entity.

The reason for doing so is that the developments in the SCS affect the political and security environment in Southeast Asia, the development of the entire ASEAN community, and the interest of individual member states. The arbitration ruling of July 2016 narrowed down the overlaping area in the SCS with the judgment that none of the land features in the SCS is entitled to a maritime zone under international law, especially the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). As a result, there appears a vast high sea in the SCS, on which all ASEAN member states — including coastal states and land-locked ones alike — enjoy rights stipulated in UNCLOS.

In parallel with the negotiations of the COC, the parties concerned need to fully and effectively implement the DOC in its entirety, especially Article 5. China has created a new fait accompli in the SCS by massively converting seven features in the Spratly Island group into concrete artificial islands, namely Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef, Gaven Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Johnson South Reef, and Hughes Reef. Ironically, Chinese President Xi Jinping, in his somnolent speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th National Congress, hailed this unilateral action as one of the “major achievements” in Chinese economic development over the last five years. As such, convincing China to destroy these artificial islands and turn back to the pre-2002 status quo is a vain effort. It is important for ASEAN member states to urge China to earnestly adhere to the DOC and refrain from any new unilateral action that may further militarize the outposts in the SCS.

Improve Communication

Fourth, Singapore can spearhead efforts to improve interactions and communications, both within ASEAN and between ASEAN and China. Hotlines among Ministries of Foreign Affairs and among Ministries of Defense must be operationalized effectively. Adopted at the 19th ASEAN-China Summit held in 2016 in Laos, the ASEAN-China MoFA-MoFA hotline guidelines suggest that once informed about a maritime emergency, the “requested party shall take appropriate action immediately to ensure effective and timely response.” The “appropriate action” has not been defined in detail, but all parties concerned must respond in good faith. Similarly, ASEAN MoD-MoD hotline, adopted at the 11th ADMM meeting in Manila, will help diffuse possible misunderstandings among ASEAN member states. These hotlines have been successfully tried and tested. The next step is to put them into practice in order to prevent untoward incidents that might occur in the SCS due to miscalculation.

At sea, Singapore can take the lead in improving communications among maritime forces. The ASEAN-China joint statement on the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) as applied to the SCS, adopted in 2016 in Laos, must be operationalized as soon as possible. At the same time, communications at sea between relevant law enforcement agencies must be improved. CUES may be expanded for coast guard vessels, but it needs further inputs in order to suit the distinct activities of coast guards.

Support ASEAN-China Maritime Cooperation

Fifth, Singapore can play an active role in fostering ASEAN-China maritime cooperation, particularly on the least sensitive issues, such as marine resources, environmental protection, and humane treatment of fishermen.

On marine resources, Singapopre may suggest the importance of establishing an ASEAN-China agreement on fishery management. Fishery resources in the SCS are important because the area contributes about 12 percent of the global fish supply (according to 2015 statistics). But overfishing as well as the use of dynamite and cyanide fishing are depleting marine resources in the region. A recent study undertaken by the University of British Columbia based in Canada predicted that fish catches in the SCS could decline by approximately 50 percent by 2045. In order to improve this bleak prospect, ASEAN and China must swiftly reach an agreement on the sustainable management of fishery resources in the SCS.

On environmental protection, Singapore may encourage ASEAN and China to draw up a treaty conducive to safeguarding the marine environment in the SCS. ASEAN member states and China at the 31st ASEAN Summit adopted a joint declaration on the decade of marine environmental protection in the SCS until 2027. Pessimistically, the declaration is symbolic as it reflects China’s effort to deflect international criticism and the arbitral ruling in regards to marine environment destruction caused by Chinese land reclamation. Optimistically, the declaration indicates that China may want to make significant progress on this matter. If so, ASEAN and China need to start to think of an ASEAN-China treaty on marine environment protection in the SCS. The treaty can incorporate important elements contained in related international frameworks like UNEP, COBSEA, and PEMSEA, among others. More importantly, the treaty should be more institutionalized and more binding in order to ensure effective implementation thereafter.

At the same time, Singapore may voice generous support for the humane treatment of fishermen, and opposition to the use or threat of force against fishermen. Fishermen are more sinned against than sinning, as most of them come from indigent coastal regions. They endure many hardships at sea and often follow fish shoals with slight apprehension of the limits of the seas under international law or maritime regulations of other states. Thus, the local authorities of states concerned should not shoot, beat, or imprison, but treat them humanely, give them a hand if possible, and swiftly repatriate them if captured. Their boats should not be sunk and their fishing equipment should not be seized or destroyed because those are the biggest assets that they possess.

In conclusion, in assuming the twin roles as ASEAN chair and country coordinator of ASEAN-China dialogue relations, there is a strategic opportunity for Singapore to promote ASEAN-China cooperation on the SCS issue. Singapore should take full advantage of this, and use great tact and diplomacy in order to preserve peace, stability, and prosperity in the SCS, further advancing its national reputation, strength, and influence.

Thuc D. Pham is a research fellow at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. The opinions expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of institutions to which the author is attached.