Trans-Pacific View author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Marcin Jaskuła – managing partner at Sino-Pol Group, a consultancy firm specializing in China-Poland projects, and partner at DealGlobe, a China Cross-Border M&A Advisory firm – is the 120th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Explain the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region’s trade and investment importance to China.

The CEE region had in recent years become increasingly important to China. The formation of the 16+1 framework in 2012 was a carefully designed maneuver to built a stronger presence of China both in a “soft diplomatic” aspect as well as providing a platform for extended economical cooperation. China was clearly a latecomer to the CEE region and is currently trying to build connections and learn the business environment of this [region] saturated predominantly by European and U.S. market players. Chinese efforts in the region already started to bear first fruits with trade and investment increasing year by year from $43.9 billion in 2010 to $58.7 billion in 2016. The main areas of the investment were infrastructure, machinery, chemical, telecom, and new energy projects. In the coming years the CEE region will gain even more significance as the Belt and Road Initiative – a massive Chinese state project – sees it as a crucial hub for its land and sea routes towards western Europe.

Describe the trajectory of China’s trade relations with Poland, Eastern Europe’s largest economy.

China is the biggest trade partner of Poland in Asia, and Poland is the largest trade partner of China in CEE. However, Poland is experiencing a trade deficit in the scale of 12.5 to 1. In 2016 the total trade value between the two countries was at nearly $26 billion, with an increase of 4.8 percent comparing to 2015. Poland’s imports from China rose by $1.2 billion and Polish exports fell by a $100 million, mostly due to the ban of exports of Polish poultry to China because of bird flu. The first two quarters of 2017 were better with a 14.6 percent increase of exports.

The Polish export structure to China is, however, still dominated by one company alone ̶ a state owned metal giant, KGHM Polska Miedź, with a net export of nearly $700 million in 2016. Other exports on the rise are in dairy, pork, furniture, and rubber products. The trend is steady – China increases its exports to Poland whereas Poland struggles to increase its exports to China mainly due to poor country branding efforts by the Polish government as well as very strict market regulations and red tape in China. Another problem is a shortage of Chinese-speaking diplomats and business advisers. Polish companies don’t understand the Chinese environment and struggle to break into the market.

What is the impact of China’s Belt Road Initiative (BRI) on Eastern Europe and Poland?

The BRI can play a vital role in Poland’s future as well as the region’s development. This historic project should, in my opinion, be received by the political and business establishment with open arms. Eleven of the 16 countries in the 16+1 framework are EU members and Chinese investments in infrastructure and energy projects will significantly ease the EU’s financial involvement and spending needs, especially with a shrinking budget after Brexit. At the same time, Chinese capital will improve the infrastructure needed to enhance the integration and economical development of CEE. It’s a win-win situation.

For instance, the government in Warsaw is currently in talks with the Chinese to get them to finance the new Central Airport for Poland, which will also be a huge logistics center with train lines and cargo facilities. Note that EU does not subsidize building new airports. However, the current EU, dominated by a Franco-German alliance, is not seeing the move as beneficiary, because it leads a way for the CEE to export more goods and services to China, which will threaten the current status quo of these aforementioned countries as leaders of EU-China cooperation.

Poland, as the largest country in the region, needs to do everything in its power to be at the center of the BRI to utilize its excellent geostrategic location as well as economical potential.

In what ways is Beijing expanding China’s influence across Eastern Europe?

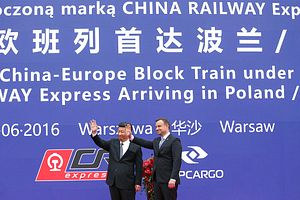

In the past few years we have seen increased marketing efforts from China to prepare the grounds for the BRI. The foundation of China-sponsored think-tanks, increased academic cooperation, a large influx of Chinese students to the region as well as growing tourist traffic are all clear signals of China’s efforts to build more influence in the region. In recent years major Chinese state-owned banks ̶ Bank of China, ICBC, China Construction Bank ̶ have all set-up shop in Warsaw, Budapest, Prague etc. Apart from receiving Chinese investments, the region is set to play a key role in the future internationalization process of the Chinese yuan (RMB). Last year Poland became the first European country to issue government debt into China’s mainland bond market. Several Chinese financed investment vehicles have been created to finance infrastructure and energy projects in the CEE (Budapest-Belgrade railroad, Montenegro-Serbia highway, etc.) We are also seeing the increased flow of M&A deals with China elements in the region, which will continue to grow in the coming years with China being the biggest player on the global M&A market. For example, HNA is the leading consortium bidding for Belgrade Airport as part of BRI and [in search of a] higher profile in the future EU member state.

Describe geostrategic dynamics in Warsaw-Brussels-Beijing relations and their importance for the EU relations with China.

It is not a secret that Chinese expansion into Poland is not seen by the EU bureaucrats as a favorable move because it can lead to lesser EU integration, which is a trend that we observe with Brexit and right-wing tendencies in countries like Poland and Hungary. The current euro-skeptic and pro-U.S. Polish administration, however, sends mixed messages to China. The presidential palace in Poland seems to favor the BRI initiative; however, the government clearly does not show that much enthusiasm. That was very clear when the current minister of national defense blocked a tender [that would have seen] a large piece of land belonging to the Military Property Agency ending up in the hands of a Chinese company and destined for development of a major logistics hub for the BRI. He cited national security reasons for that matter.

Another important geostrategic dynamic is that the EU structural funds for development will stop in 2020, and Poland needs to seek alternative investment vehicles to prolong its GDP growth. Huge investments are still needed in infrastructure (especially train lines and the energy sector). Therefore, Poland needs a long-term political strategy toward China and BRI in order to win the competition with countries like Hungary and the Czech Republic and secure its top spot on the BRI map.