In recent months, the Indian government has been eager to restore “normalcy” to the troubled Kashmir Valley. Hoping to stymie the latest wave of unrest, which began suddenly in the summer months of 2016, the central government has placed its faith in an interlocutor to pursue a “sustained dialogue” with local stakeholders. The appointee, former Intelligence Bureau Chief Dineshwar Sharma, now faces a dire situation: after last year’s protests broke out in response to the targeted killing of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani, Kashmiri disenchantment has deepened and the militancy has begun to attract new pockets of local support. Last month, thousands poured into the capital city’s streets to attend the funeral of the militant Mughees Ahmed Mir, despite curfew restrictions.

Still, officials have been eager to broadcast their belief that the valley will return to normalcy, with the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) police chief crediting the success of intensified counterinsurgency operations to a 90 percent drop in stone-pelting, a form of political resistance popular with Kashmiris since 2010. Statements like these expose a decisive flaw in India’s approach to political dissent in the valley, including the decades-old reservoir of separatist sentiment that has gained support in the past year. Unless the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) revises its law and order approach to the valley to acknowledge the depth of Kashmiri discontent, overtures toward dialogue will be ineffective and the situation in the state will only deteriorate.

Enduring Political Alienation in the Valley

The 2016 protest wave exposed the unresolved contours of Kashmiri discontent. Similar uprisings had unfolded over the summers of 2008, 2009, and 2010. But when the 2016 protests erupted, it became clear that Kashmiri disenchantment with the political establishment had reached new heights. The scale and persistence of the protests is evidence enough: in the immediate aftermath of Burhan’s death, 200,000 people attended his funeral prayers. Over the next few months, approximately 90 protesters would be killed and 17,000 injured due to the widespread use of non-lethal pellet guns by Indian security forces.

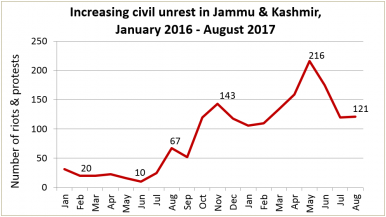

Ultimately, India must come to terms with the reality of political alienation in the valley. Contrary to the J&K police chief’s claim, the most recent data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (see Figure 1 below) suggests that civil unrest has not yet been restored to pre-Burhan Wani levels. Rather, the number of protests and riots in Kashmir rose on average between 2016 and 2017, concluding August 2017 at a level ten times higher than the month before Burhan Wani’s death. Notably, May 2017— the same month during which a Kashmiri man was used by Indian security forces as a human shield against a stone-pelting crowd — contained the highest degree of unrest of the time period analyzed. The data indicates that frequent political resistance activity has become commonplace as a “new normal” of unrest takes hold in Kashmir.

Figure 1. Civil unrest in Jammu & Kashmir. Source: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

In the face of such enduring alienation, dialogue is imperative. Though the interlocutor’s appointment is a positive step in the right direction, India could do more to assure skeptical locals — who have seen past interlocutors come and go and are skeptical this recent appointment will do much to alter the state’s patchy history of dialogue — that it is serious about pursuing a political solution. Most importantly, though Indian government officials often claim Pakistan is the primary reason for unrest in the valley, it is a mistake to discredit the homegrown nature of Kashmiri dissent. Instead, the central government should recognize that stone-pelting and other forms of protest can be attributed to its own decision to disregard telltale signs of discontent and carry on with a hardline security policy, which has fueled popular anger. To signal its seriousness, India could, at a minimum, direct the Central Reserve Police Force to abandon its use of high-lethality crowd control tactics, which have been under fire since 2008. Instead, it could deploy non-lethal riot control equipment, previously approved in 2012, and train police personnel to use this equipment appropriately to respond to uprisings without provoking further outrage.

Kashmir’s Revived Militancy Problem

India’s confidence surrounding the effectiveness of its harsh counterinsurgency operations is also misguided. An enemy-centric counterinsurgency strategy that focuses on rooting out known militants will be ineffective if renewed support for the insurgency ensures a steady flow of recruits to replace those who have perished. The most convincing evidence in favor of an alternative approach is India’s own history with counterinsurgency in Kashmir: according to political scientist Sumit Ganguly, India only began to defeat the insurgency that defined Kashmir in the 1990s after the government pivoted toward a strategy of “minimal force” with Operation Sadhbhavana (literally meaning “goodwill”). To treat Kashmir as a primarily law and order problem was, and remains, a strategy destined for failure.

The numbers paint an ominous picture of the conditions on the ground, substantiating reports that militancy has been on the rise since Burhan Wani’s death last year. In fact, data from the South Asia Terrorism Portal reveal a surge in terrorism-related casualties, from 267 in 2016 to 331 in 2017. The data also reveal the larger trend of rising casualties from terrorism since 2012, indicating that the central government has been confronting an invigorated militancy for some time. In particular, terrorist casualties have gradually risen, which is suggestive of an enhanced counterinsurgency campaign. However, given that this number has increased nearly every year since 2012, this is likely due to an expanded presence of militants in J&K as opposed to the success of a particular counterinsurgency strategy. Still, officials from the army, police, and central government continue to repeat the mantra that Kashmir will “soon return to normal,” failing to acknowledge that 2016 was not a spontaneous event. In reality, militancy in the valley has been on the rise for the past five years and has generated further momentum since the 2016 unrest.

Similarly, the dynamics of radicalization and militancy appear to be transforming in a disturbing way. Early this summer, al-Qaeda established an affiliate in the valley, Answar Ghazwat-Ul-Hind (AGUH), and the group has seemingly gained ground in Kashmir. According to local reports, the body of slain militant Mughees Ahmed Mir was draped in a black Islamic State (ISIS) flag during his funeral procession — with no green Pakistani flags in sight. Importantly, AGUH’s chief commander in Kashmir is Zakir Musa, a one-time local Hizbul Mujahideen commander who has advocated for Kashmiri jihad and criticized Pakistan for its “betrayal” of Kashmiri Muslims. These reports have ramifications on India’s Kashmir policy: if Pakistan were the primary reason for militancy, it is improbable that Musa’s jihadist ideology would gain traction, likely at the expense of pro-Pakistan sentiment. It also means that the militancy problem in the Kashmir Valley is on course to becoming increasingly tied to global jihadist movements such as ISIS, a threat that should compel India to seriously reexamine its posture toward the state.

A “War-Like” Situation

Local reports and open-source data suggest the situation in Kashmir is, as Finance Minister Arun Jaitley stated earlier this year, becoming progressively “war-like”: a once-dwindling militancy has been revived, unrest has yet to return to pre-2016 levels, radical jihadist ideology appears to be gaining ground, and funeral processions for militants continue to attract thousands. Though interlocutor Sharma has urged the central government to maintain an “open mind” in its approach to Kashmir, the central government’s hardline security strategy has taken precedence over the pursuit of dialogue. Even J&K’s centrist Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti recently advocated for a “humane approach” to the problem, stating “militancy cannot be wiped out by killing militants alone.” Still, a reversal of the BJP’s hawkish policies seems unlikely given that most Indians are in favor of an increasingly forceful approach to Kashmir. If New Delhi does not confront the realities of Kashmiri discontent, normalcy will remain out of reach for the Valley.

Emily Tallo is a graduate of Indiana University’s School of Global and International Studies and a researcher at the Stimson Center’s South Asia Program.