One Bollywood movie made by a filmmaker known for opulence in his movies has drawn the attention of India for all of November. Except, this movie hasn’t yet been released. Padmavati, a period drama from 16th century Western India, has been accused of distorting “historical facts” by Shri Rajput Karni Sena. This violent right-wing vigilante group of the Rajput community has been known to disrupt law and order whenever the arts push the envelope with perspectives of history.

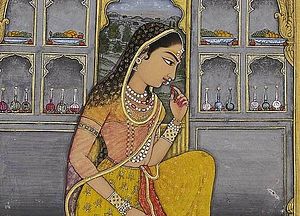

The movie is an adaptation of Padmavat, an epic poem penned in 1540, that describes the conquest of parts of the Rajput kingdom by the Muslim Turko-Afghan ruler Alauddin Khilji, who also sought to capture Queen Padmini. The queen is said to have immolated herself, in a practice known as “jauhar,” to protect her honor. However, the bone of violent contention for the Karni Sena is a supposed love scene in the movie, between Khilji (played by actor Ranveer Singh) and Rani Padmini (actor Deepika Padukone) as a dream sequence.

Earlier this year, the Karni Sena beat up the filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali and vandalized the set where the movie was being shot in Rajasthan. They then burnt down the movie set when it was moved to another location. Earlier in November, a group of people vandalized a mall in Rajasthan’s Kota town when the movie’s trailer was screened.

As the date of the movie’s release neared – December 1 – the movie turned into a political puppet, as the heads of various states called for a ban on the movie, and chose silence regarding the violence meted out by Karni Sena. Mahipal Singh Makrana, one of the leaders of the Karni Sena, threatened to chop off Padukone’s nose for her role in the film: the nose being associated with honor. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) chief media coordinator for the northern state of Haryana announced a massive reward for anyone who beheads Padukone and Bhansali. Padukone and her family were given police protection.

Two petitions reached the country’s Supreme Court challenging the release of the movie and criminal prosecution of the movie’s makers, but the pleas were dismissed by the Court on the grounds that the movie had not yet been certified by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC).

Filmmakers and workers in the movie industry across India protested the violation of the right to freedom of expression by halting their work for 15 minutes. Viacom18 Motion Pictures – the co-producers of the movie – “voluntarily deferred” its release.

What’s surprising is that even as Rajasthan continues to suffer among the worst sex ratio in the country, the Karni Sena choose to valorize a questionably-historical-part-fictitious person from history, for her death by fire, as proof of her devotion to her husband: an act that reduces women to mere sacrificial lambs in the name of honor.

“Sati” or “jauhar” – widow immolation – was largely practiced in Rajasthan among Rajput women. According to a few accounts, the earliest instances of jauhar resulted from Rajput internecine warfare. Raiding neighboring Rajput kingdoms to steal princesses was a common practice among the Rajputs.

The practice was abolished in 1829. However, it reared its ugly head sporadically thereafter. In 1987, the news of a young Roop Kanwar who jumped into her husband’s funeral pyre flashed across the country. It was the 38th such incident in independent India. The news sparked controversy: there were contrasting views on whether she jumped into the pyre on her own, or was dragged into it. A fact-finding investigation undertaken by the Network of Women in Media, India (NWMI) found that the location of the incident was deified; a large section of the Rajput community saw it as a courageous act, intrinsic to the Rajput culture. It was believed that a lower caste woman could attain salvation and be born a Rajput male in their next birth if she attains the death through sati. The state president of the BJP in Rajasthan at the time actively opposed the ‘interference’ of the government in what he considered a religious rite.

But the recent attacks by Karni Sena is a blatant display of patriarchal masculinity, wherein any deviation from the deified idea of a historical woman is meted with violent rebuttals. Apart from the discussion about the trampling of the freedom of creative expression and cinema that offers a possibly hitherto unheard of perspective of history through imagination, Karni Sena is not among the first to cause a violent uproar. Myths seem more convenient to revere than the reality: that Padukone has been threatened with dire violence for portraying a valorized mythical woman is the obvious irony. But critics also question whether this ire is directed towards depicting a Rajput woman in a love sequence – that too, a dream one – with a Muslim man.

This isn’t the first such instance of a movie raking up wild anger that goes unpunished. In the 1970s, a play titled Sakharam Binder by Marathi theater doyen Vijay Tendulkar was banned: it told the story of a man who brings home the castaway wives of others.

Amrit Nahta’s Kissa Kursi Ka, a political satire on the Emergency imposed in 1975 by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was destroyed on the order of Gandhi’s son and Indian Youth Congress leader Sanjay Gandhi. The prints and the original negative were confiscated and burnt. The movie was remade in 1978 when the Janata Party came to power.

In 1995, ace filmmaker Mani Ratnam’s Bombay explored the romance between a Hindu man and a Muslim woman, with the 1992 communal riots in Mumbai as a backdrop. Ratnam was forced to edit out scenes which showed a character – based on Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray – inciting rioters. Muslim groups also demanded a ban for the inter-religious romance.

In 1998, Deepa Mehta’s Fire which depicted a lesbian relationship between sisters-in-law, faced the wrath of members of Shiv Sena and Bajrang Dal who vandalized property at cinema halls across Indian cities and frightened away audiences. The movie was released uncut. Later, in 2000, Mehta’s detractors stalled the shooting of Water in Varanasi. The movie is set in British India and depicts the exploitation of widows. After severe violence at the ghats in Varanasi and threats to the actors and Mehta, the movie was filmed in Sri Lanka and was completed five years later.

Anil Sharma’s Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001) was a love story between a Sikh man and a Muslim woman, set in Partition. A sequence in which the woman is shown offering namaaz (prayer offered by Muslims) while wearing vermilion on her forehead (a symbol of matrimony among Hindu women) sparked a series of protests, including a cinema hall in Bhopal being attacked by men with swords, petrol bombs, stones and rods.

In 2008, the Karni Sena accused filmmaker Ashutosh Gowariker of distorting history and misrepresenting the Rajput community in his 2008 movie Jodhaa Akbar. The movie was not released in several states, but this arbitrary ban was lifted after the Supreme Court’s intervention.

Bhansali, who has made Padmavati, had adapted Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in 2013 and titled it Ram Leela. Some Hindu groups objected to the fact that the protagonist Ram, depicted as an alcohol-swilling womanizer, shared his name with the Hindu god. The movie was subsequently titled Goliyon Ki Rasleela.

More recently, two movies were not allowed to be screened at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) 2017: Sexy Durga follows the journey of a Muslim man and his Hindu girlfriend on a road trip across India, while Nude is the story of a poor woman who works as a nude model for art students.

At a time in India where secularism has become congruent to only a selective acceptance of religious identities, and gender equality has become synonymous with women taking pride in proscribed stereotypes from a patriarchal gaze, the events associated with a movie speaks volumes of the lows of intolerance. One could brush away these incidents as just a controversy that could generate more interest for the movie among the non-concerned public, and that it may not be a case of basic needs being stripped away. But in the absence of freedom of speech – one in which the actors and makers of Padmavati have been threatened with dire consequences – the silence of the state governments and their words of condonement are truly worrisome.

Never mind that gender equity continues to ail every village and town and city in India. Never mind that a woman’s choice of what she chooses to honor in her life is gutted in the name of the honor of the society at large. Never mind that precious hours of the judiciary could be better spent in hearing cases of atrocities against women and those in lower rungs of the society. Each time a movie is opposed with violent bursts, the larger problem of an allergy towards religious sensibilities manifested in the machismo in India is magnified.