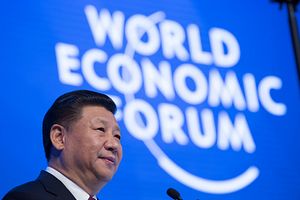

Speaking at the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress in October, President Xi Jinping rallied attendees around a grand pronouncement. China had “taken a driving seat in international cooperation to respond to climate change,” Xi declared.

To most onlookers, Xi’s messaging at the Congress couldn’t be clearer. The quinquennial event came against the backdrop of the United States’ retreat from international climate diplomacy, and its isolationist turn inward under the Trump administration. Without directly mentioning the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, its rollback of environmental regulations, or its planned coal subsidies and offshore drilling, Xi left little doubt that in the absence of U.S. leadership on climate change, he intended for China to step up.

Xi’s rhetoric was especially striking given China’s historic role as a pariah in climate negotiations. For decades before Xi, China’s leaders argued for their country’s right to industrialize the way developed countries before it had — with a period of emissions-heavy, resource-intensive growth followed by a gradual transition to sustainable development. This rationale helped China and other developing countries skirt strict regulation under agreements like the Kyoto Protocol.

Despite this checkered past, China’s record under Xi has been different. On a national level, China has methodically added renewable energy capacity, cut back on heavy industries, invested hundreds of billions in development of green tech and experimented with a host of novel ways to reduce air pollution. It has also positioned itself to become a leading global manufacturer of renewable technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, and cheap electric vehicles, which it exports to other developing countries, lowering carbon emissions abroad as well.

By any measure, China’s transition to a more sustainable future has already been exceptional. Its singular transformation from an economic backwater to a global industrial power that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty alone is remarkable. But using tight state control and the command economy, Beijing has also been able to enact environmental reforms far more rapidly and effectively than many other countries.

This year alone, the government shut down over 100 coal-fired power plants, and forced many that have already been built to sit idle. It has also planned the world’s largest carbon market that will use a cap-and-trade system and credits to further lower emissions in the future.

Although under the Paris Accord, China officially signed on to an agreement to let its carbon emissions inch upwards until 2030, by most measures, China appears far ahead of that target. According to most estimates, the country’s emissions may have already hit their peak in 2014, and are beginning to come down more than a decade ahead of schedule. Through this rapid progress, Beijing has been able to almost singlehandedly affect the trajectory of global carbon emissions. This month, for the first time since it began tracking global emissions in 2009, Climate Action Tracker revised its end of century temperature forecast downward due to unexpected cuts in carbon emissions from China and India.

Yet beyond the fanfare about its forward-thinking climate policy and newfound role as a global leader, China’s recent strides should be understood in a global context. As much as Beijing has done to get its own house in order and lay the foundation for a more sustainable future domestically, it hasn’t always let concern over climate change inform its trade policy or diplomacy.

Most of all, as China is beginning to shy away from coal, it is increasingly taking its excess coal capacity abroad. As of last year, China was involved in nearly 80 overseas coal plant projects around the world, making it far and away the largest exporter of coal power technology and equipment. Of course, this can also be seen as a strategy to ensure overseas demand for Chinese coal, which it can export abroad freely without increasing its own emissions statistics.

Beijing’s One Belt One Road initiative — a plan to finance major infrastructure projects throughout Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa — is a similar phenomenon. As the demand for steel, concrete, and other industrial products at home as slowed, China has increasingly sought to transfer overcapacity abroad. While endowing its neighbors with more roads, airports, factories, and warehouses certainly brings important economic benefits, it inevitably means that these countries will also see rising emissions of their own in years ahead. It also gives Chinese heavy industry reason to keep producing, and perhaps also incentivizes Chinese corporations to find overseas sites for new factories and steel mills, closer to these new construction projects.

Finally, as effective as China has been at reducing its own emissions in a meaningful way over all, this has often come at the expense of some of its own citizens. Though a growing percentage of China’s more than 1.3 billion people are moving to more efficient, modern urban areas, and taking jobs in an expanding services sector, those left behind have typically shouldered the burden of China’s transition. According to a 2013 study, a small subset of industrial provinces is contributing more and more to the country’s emissions from manufacturing.

While China isn’t unique in having a few industrial pockets that manufacture the lion’s share of products consumed elsewhere in the country, the study found that the divide is growing. So while China is becoming a cleaner, lower-emissions country on a national scale, provinces such as Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and Guangdong have become sites of concentrated air and water pollution. And though the concept of environmental justice has yet to inform social debate in China in a significant way, it is clear that Beijing’s efforts to over-perform on reducing emissions have disproportionately impacted Chinese citizens living in poorer, more industrial areas.

China’s leaders are clearly justified in taking some pride in the headway made in recent years. Rather than lumber on as the world’s largest carbon emitter through 2030, the country as a whole has been proactive: sharply cutting emissions and pouring huge sums into sustainable energy and other green technology. China shares many of the same concerns about climate change as other countries, including rising sea levels, desertification, and water scarcity, given its large coastline and relatively little arable land. In that sense, there are real reasons for its leaders to take earnest steps toward getting global emissions in check.

But it is also fair to question what China’s real objectives are in making these changes, and whether it has been willing to prioritize climate goals over business thus far. Xi’s remarks suggest that Beijing’s primary interest is winning China the image of global climate leadership, without necessarily leading other countries toward a sustainable future. China can and should continue its laudable efforts to lower its own emissions. But as long as Chinese corporations continue to lead other countries into the same carbon-intensive development model that China followed over the past several decades, any of its own contributions to lowering global emissions may well be offset.

Zach Montague is a news assistant at The New York Times and a graduate of the China and Asia Pacific Studies program at Cornell. He has previously worked in Abu Dhabi, Beijing, and Shaanxi. Follow him on Twitter at @zjmontague. This article was originally published on China-US Focus, an initiative of the China-United States Exchange Foundation (CUSEF). The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and do not necessarily reflect the views of China-US Focus.