Back in 1776, Adam Smith observed that “all the inland parts” of Africa and Asia were the world’s least developed areas. Even today, well over two centuries later, most of these landlocked countries are still trapped in poverty. Countries without direct coastal access to the sea and to maritime trade face many challenges from the outset that limit their potential gains from trade in this globalized world compared to their coastal neighboring countries. The Human Development Index is a stark indication of how poorly landlocked countries are performing: low standards of living, high child mortality, high levels of poverty, low health care quality, and crippled education systems. In the Human Development Report of 2016, 10 out of the 32 countries with the lowest HDI scores are landlocked.

In today’s competitive world, it is an understatement, to say the least, that landlocked countries generally face a difficult situation. Although being landlocked is a challenge, it is not destiny. Afghanistan – a landlocked, underdeveloped country – is taking practical steps, discussed below, to turn the liability of being a landlocked country into an asset for the prosperity of this war-torn nation.

Afghanistan is one of 48 non-coastal counties in the world. It is surrounded by six countries: Iran in the west, Pakistan on the southeast, and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and China in the north. The two closest sea ports to Afghanistan are Karachi port in Pakistan, which is 1,406 kilometers away from Kabul, and Iran’s Chabahar, which is farther away — about 1,840 kilometers from Kabul. Pakistan and Iran are the top two sources of import for Afghanistan, representing total import market shares of 17.22 percent and 22.83 percent, respectively, in 2016. India, Pakistan, and Iran are the top three export destinations for Afghan products, with total amounts of $220 million, $199 million, and $15.1 million, respectively, in 2016.

Afghanistan not only faces the challenge of distance but also the challenges that result from dependence on a sovereign transit country, through which trade from Afghanistan must pass in order to access international shipping markets. In the post-Taliban era, Pakistan and Iran both have used their trade routes for political leverage over the Afghan government. In November 2011 when a U.S. unmanned drone killed 24 Pakistani soldiers, the government of Pakistan decided to block the supply route to Afghanistan in retaliation. Thousands of Afghan-bound containers loaded with commercial goods were stranded in the port city of Karachi. Perishable goods were spoiled and non-perishables were grounded for weeks, which resulted in massive losses for businesses.

Due to these challenges, Afghanistan had a 77 percent trade imbalance last year, with a $3.2 billion trade deficit. In order to address the lack of access to the sea, for the first time, the Afghan government has developed a five-year blueprint for infrastructure development that highlights structural challenges for this landlocked country and the way forward for transforming Afghanistan from a landlocked country into a land-connected country.

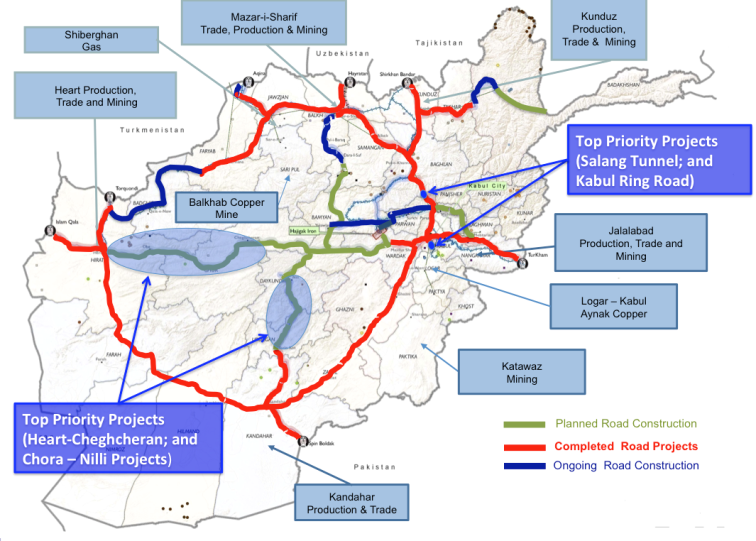

Infrastructure remains a critical constraint for Afghanistan. While significant infrastructure investments and improvements have been achieved since 2002, there are still major gaps constraining growth due to poor transport connectivity; barriers to regional market integration; incomplete policy and regulatory reforms; institutional capacity and human skill constraints; ongoing security conflicts; and limited operations and maintenance funding for existing infrastructure. The government strategy is to improve infrastructure investment efficiency. Infrastructure investments into an integrated transport network, systematically planned and implemented, are focused on facilitating the country’s economic growth and development through expanding access to domestic, regional, and international markets and social services; increasing employment; and spurring trade, transit, and logistics. This will involve rail linkages and road investments, including completing the Kabul ring road, border road connections, Salang Tunnel and access roads, and road operations and maintenance programs; urban transport; civil aviation; trade facilitation; dry ports; and transport logistics. In addition, the infrastructure plan outlines a roadmap for regional connectivity with efficient infrastructure delivery that creates jobs and connects goods to markets in Afghanistan and the region. This regional connectivity will be achieved through improved transport systems, freight, and logistics supply chains; energy supply; and high-speed telecommunications.

Given the enormous geopolitical shift in the region, Afghanistan is in a unique position to utilize its geographic dividends and serve as the regional hub connecting Central Asia and South Asia as well as China to Europe in an east-westerly direction. The Infrastructure Plan streamlines the following investments to support regional opportunities that have strong domestic returns and benefits.

Planned regional energy projects. Image courtesy of the Afghan Ministry of Finance.

Moving Energy

Afghanistan will serve as the utility corridor connecting the energy-rich Central Asian nations to energy-poor South Asia. There are three projects that are currently in the pipeline: the TAP transmission line that would initially move 2000 megawatts (MW) from Turkmenistan to Pakistan via western Afghanistan and could eventually carry up to 4000 MW; the TAPI gas pipeline that will transport natural gas from Turkmenistan to Pakistan and India via Afghanistan; and the CASA-1000 transmission lines that will move over 1000 MW of electricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Pakistan via Afghanistan. These three projects are building on earlier work, and are the next stage for bulk energy transfers regionally.

The three projects will require large investments, with TAP having an estimated cost of $500 million, TAPI $12.5 billion (with $7 billion to be sourced from the private sector), and CASA 1000 $1.17 billion.

As an example of the opportunities that may exist, Pakistan is expected to need more than 15,000 MW of additional electricity in the coming decade, and one of the most economically viable and environmentally sustainable sources of supply for this forecast demand would be such bulk power transfers from Central Asia via Afghanistan to Pakistan.

Afghanistan ring road map. Image courtesy of Afghan Ministry of Finance.

Moving Goods and Merchandise

Moving goods and merchandise across Afghanistan to the region is a top priority. The National Infrastructure Plan transport sector priorities reflect the importance of regional trade connectivity, and the national priority of completing the ring road. Three of the six Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) corridors have a major link in Afghanistan synchronous with the national highways. In addition, in the context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Afghanistan will be along the corridor connecting Tajikistan with Iran via Afghanistan’s border towns of Sher Khan Bandar and Bandar Islam Qala. Similarly, later this year the Turkmen railroad will reach Aqina on the Afghanistan border, paving the way for the Lapis Lazuli Corridor, which offers an alternate route for goods from China as well as imports and exports from Afghanistan to get to Europe via Turkmenistan and the Caspian Sea.

Afghanistan’s proposed railroad beltway will provide new opportunities.

The government has prioritized three regional rail investments. The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Iran line will include extensions of the Islam Qala line extension (from Joye Now) to Herat, and the Torghondi-Herat link, which connects into the Lapis Lazuli route. The Aqina to Andkhoy rail link has seen design work completed and construction will soon follow. Finally, the Northern Line (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Tajikistan) rail link connecting Andkhoy, Sheberghan, Mazir-e-Sharif, Kunduz, and Sher Khan Bandar, would link to China through Tajikistan.

The national railway plan has also identified opportunities that exist for railway spurs to Pakistan via Torkham and Spinboldak ports, which will facilitate the movement of goods to and from Pakistan to Central Asian countries. Similarly, with the development of Chabahar and Gwadar ports, Afghanistan can provide the most economical route for Central Asian countries to reach international markets and to connect with the Arabian Peninsula and beyond both for imports and exports.

Trade facilitation and transport logistics are a government priority, as outlined in the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANPDF) transport sector masterplan, and in the CAREC Transport and Trade Facilitation Strategy 2020. To improve the country’s trade competitiveness and lower the cost of transport logistics for regional connectivity, priority projects to support large infrastructure investments will include improvements to border crossing points and the development of multi-modal hubs, dry ports, and logistics centers. In addition, the government will improve standardization of procedures, and regulations, computerization, and address other constraints to market development and growth (lack of trade finance, cold storage facilities, and insurance). The high cost of transport logistics reduces the country’s trade competitiveness.

Moving Data

As currently roughly half of the world’s internet traffic is between Asia and Europe, the future is with data transfer opportunities. The current data transfer pathway can handle approximately 15 terrabytes per second using the maritime fiber that runs under the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal, and the Red Sea, passing through the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent and finally wrapping around Asian markets. This pathway has several problems. First, maritime cables are more prone to damage, and require more maintenance. Second, given the long pathway, it takes roughly 130 milliseconds for data to make the trip.

The digital CASA program and the fiber optics networks will increase internet connectivity by catalyzing private sector investment in infrastructure and modernizing relevant policies and regulatory frameworks. Currently, internet penetration remains low across the CASA countries, despite high levels of mobile cellular penetration, in part due to high costs. The government’s recent approval of an open access policy to remove the existing monopoly will enable telecommunication companies to actively invest and where necessary form public-private partnerships, which will result in lower costs and expanded user services and access.

As part of the TAPI gas pipeline, Afghanistan will be installing fiber that will connect India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan. Additionally, as part of the Trans-Eurasian Information Superhighway (TASIM) project, the above fiber will be connected under the Caspian Sea to the port of Baku and then to Italy. In other words, Afghanistan can be the most efficient pathway to provide a shorter and more reliable data communication route between Europe and Asia. This would potentially reduce transmission time by over 30 milliseconds. Moreover, the route will offer an alternate pathway to the Trans-Siberian fiber.

The connectivity projects outlined above have the potential to generate significant transit revenue for Afghanistan. This is particularly the case with regard to the proposed data movement (TASIM and Digital CASA), which could raise several hundred million dollars in the long-term. TAP could generate $200 million or more, while CASA-1000 transit fees are estimated to be $40 million.

In sum, Afghanistan is adopting a model that would transform this country into a regional hub for the movement of energy, goods, and data across the region in the near future. Given the enormous geopolitical shift in the region, Afghanistan is in a unique position to utilize its geographic dividends and serve as the regional hub connecting Central Asia and South Asia as well as China to Europe in an east-westerly direction. As a utility corridor, Afghanistan will connect the energy-rich Central Asian nations to energy-poor South Asia. In addition, three of the six Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) corridors have a major link in Afghanistan, which makes it easier to transfer goods to different countries. Finally, as currently roughly half of the world’s internet traffic is between Asia and Europe, Afghanistan is well positioned to provide a shorter and more reliable data communication route between Europe in Asia that can potentially reduce the transmission time.

Abid Amiri is the Director of Policy Analysis for Infrastructure, Urban, and Mining National Priority Programs at the Ministry of Finance in Afghanistan.