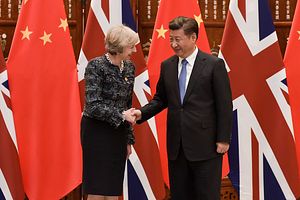

It has been a long time coming. British Prime Minister Theresa May did visit China, very briefly, just after her elevation (she was appointed unopposed as David Cameron’s successor when potential competitors pulled out of the leadership race for the ruling Conservative Party in mid-2016). But this was to attend the G20, which happened to be convened in Hangzhou that year. Her trip to China from January 31 to February 1 will be her first purely bilateral visit.

She will go under very unique circumstances. Brexit is proceeding, but with all of the complexity and frustration that was suspected when the shock result of the June 2016 referendum became clear. The visit to China therefore is the first stab at scoping out what a post-EU Sino-U.K. relationship might look like. She cannot, of course, talk about free trade deals; that can’t happen till the United Kingdom finally leaves the Union. But she can at least set out a vision to her Chinese interlocutors, making it clear that the so-called Golden Era between the U.K. and China, announced during Xi’s visit to Britain in 2015, is still ongoing — it might be about to get even more golden.

May has some big challenges to face in achieving this. The fact that it has taken so long to get to China in the first place suggests complacency, even if there were many good reasons back home for her being so slow to get on a plane to Beijing. The Xi leadership is in the market for flattery, and hungry for status. A visit weeks after May was appointed might have carried a lot of weight with them. As it was, she spent most of that time reconsidering the Chinese equity investment in the Hinkley Point nuclear power station, something that most had assumed was already approved.

That she is coming to China as a country about to walk away from the world’s best, and largest, free trade deal, will no doubt baffle the Xi leadership. For a country that at least says it believes resolutely in noninterference in the domestic affairs of others, Xi came as close as he could to saying in 2015 that he felt the U.K. was best staying in the EU. The fact that, according to a report in the Financial Times on January 26, May had been asked to formally recognize the Belt and Road Initiative and was reluctant to do so is ominous. China may well feel like they are dealing with a country that is now finally a plaintive, rather than a major force in its own right. And they are already applying the principle of “ask for the outrageous – they might just consider it.”

And the U.K. might just be more biddable with China than ever before. On Hong Kong, beyond issues of direct national concern, London has been told, by no less a person than Xi himself when he marked the 20th anniversary of the handover, to keep out. On human rights issues generally, the U.K. outside the EU will be exposed as never before, because it was through the 28 member state collection that most of these contentious issues were dealt with. On top of this, with access to the single market and the customs union for the U.K. due to stop on current terms in a few year’s time, suddenly a large, relatively undeveloped economy like China’s becomes increasingly interesting. The U.K. will need to increase investment, trade, and finance flows as never before with a country it has a long but complex history with, and still relatively small amounts of real economic engagement.

A good Brexit, as far as the U.K.’s relationship with China goes, will get rid of the complacency, and encourage British companies, institutions, and people to engage with the People’s Republic as never before. That will mean acquiring a large amount of cultural, linguistic, and political knowledge, which, outside of specialist elites, is not there in sufficient quantities at the moment. The Golden Age was the first strike to shift some of this complacency. Brexit will continue that need. The U.K. does have a basis for deeper and better engagement with China, and a relatively positive story. In 2017, for instance, it attracted half of the Chinese investment into Europe.

They key thing for May to convey to Chinese leaders is that in the areas where the relationship matters most, at least to their governments – investment, finance, and intellectual partnership – the U.K. will be as, if not more, attractive on leaving the EU. That will make China listen. It is not likely that there will be much space in this dialogue for the old style arguments about values and rights issues. That conversation will have to happen, and the U.K. will need to think hard about what values it wants to promote, but any temptation to lecture will be met with a much fiercer pushback than in the past. And there might be the perception of economic costs, even if in fact it is hard to prove if spats about these issues ever really do impact the bottom line of practical cooperation.

May is a conscientious and earnest politician. She is not a particularly subtle one. But the message she has to convey in Beijing is pretty multifaceted. It is that the U.K. has a vision for Brexit, that it means upgraded relations with China, but not that the U.K. will become a Chinese vassal in Europe, doing its bidding and cowed by its orders. She can’t be too forceful on rights issues, but she can’t appear heedless of them. As with so many other things, exiting the EU is proving to have created a deal of complexity. This has become almost Maoist in its confusion and disruptiveness. If May wishes to cheer herself up during the travails of being in Beijing in the next few days, however, she can always comfort herself with one of the Chairman’s most famous sayings: “There is chaos under Heaven. The situation is excellent.”