With continued international concern over the treatment of Rohingyas in Myanmar, some commentators have suggested the use of sanctions to varying degrees. This would not be the first time that Myanmar faced sanctions. The United States imposed sanctions on Myanmar in 2003 and revoked them only in 2016, and Washington has recently also begun imposing some targeted sanctions following the Rohingya crisis. In this article, we discuss the impacts and coping strategies related to the sanctions imposed on Myanmar, which lasted over a decade.

Sanctions aim to restrict the commercial relationship between the imposer country and the target country. Economic sanctions on Myanmar included cuts in financial aid, blocking access to assets, and reversing investment flows. The U.S. Treasury Department classifies sanctions as “selective” or “comprehensive.” Comprehensive sanctions include asset freezes, trade embargoes, and financial restrictions to inflict financial losses. Selective sanctions, on the other hand, are imposed on influential individuals in the target country.

In 2003, the United States and OECD countries imposed comprehensive sanctions on Myanmar. Now that the sanctions are lifted, it is an opportune time to conduct a forensic analysis of the fallout from these long-lasting restrictions on Myanmar, particularly as calls increase for renewing the sanctions regime.

There are several important takeaways.

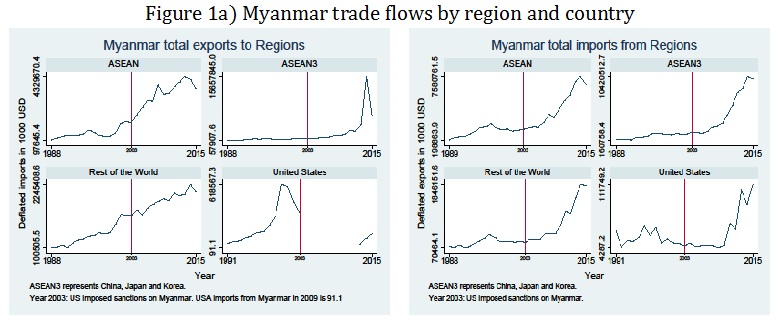

First, the sanctions enforced were highly asymmetric in nature. After enforcement, Myanmar’s exports to the United States dropped to zero, but the U.S. continued to export its products to Myanmar (see figure 1a).

Second, even though sanctions were wide-ranging, an IFPRI study shows that at the aggregate level, the impact of sanctions on Myanmar’s trade was insignificant. In 2001, before the sanctions, Myanmar’s total trade stood at $6.28 billion, which increased to $6.54 billion in 2003. The total trade of Myanmar increased without interruption even after the sanctions. In 2004, its overall trade rose to $7.1 billion and further increased to $8.57 billion in 2006.

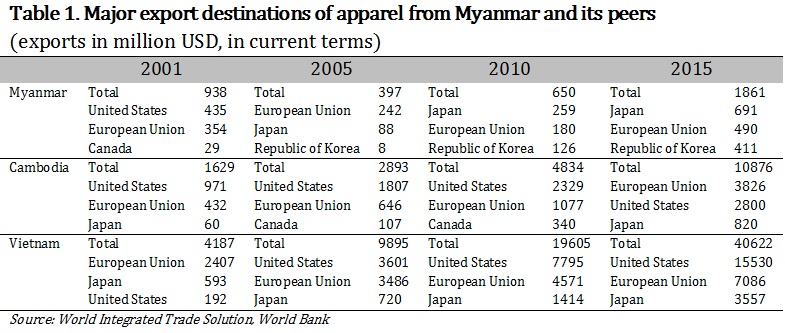

During sanctions, Myanmar diversified both its products and its trading partners. While data clearly shows that the textile industry of Myanmar (one of its principal exports) took a hit from sanctions, there was a substantive market reallocation effect. ASEAN+6 emerged as a significant shock absorber for textile exports. Table 1 shows a sizable readjustment just as exports to one of the main markets for Myanmar textiles — the United States — dried up. In 2001, before the sanctions, Myanmar exported around 46 percent of its apparel to United States. After the sanctions enforcement, total apparel exports of Myanmar fell by nearly 58 percent in 2005. At the same time, Myanmar diverted its exports to South Korea and Japan quite significantly.

Table 1 is inspired by Koji Kubo’s 2014 study, “Myanmar’s non-resource export potential after the lifting of economic sanctions: a gravity model analysis”

Unlike textiles, the export of jadeite and rubies from Myanmar was allowed on a condition of re-export from the United States to other countries. This tweak preserved one of Myanmar’s most important exports.

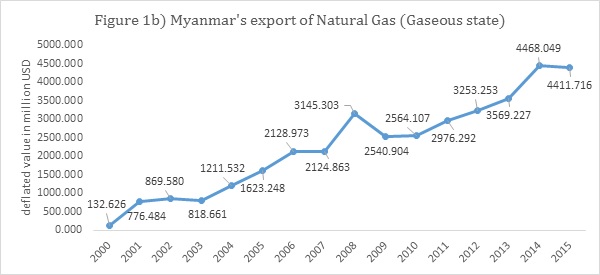

Further, one of the more remarkable impacts of sanctions was the structural break in natural gas exports. To what extent this spurt in gas exports was caused by the sanctions remains an important research question to address. Our analysis shows that during the period of sanctions, Myanmar increased the supply of its natural gas very significantly. In 2003, before sanctions were imposed, Myanmar exports of natural gas stood at $819 million. By 2015, it had risen to $4.4 billion (figure 1b). Moreover, it rose consistently, growing at a compound rate of over 26 percent, sterling growth by any yardstick. Myanmar exported natural gas mainly to Thailand, China, and Singapore, thus bypassing sanctions.

What are the main takeaways from the experience of sanctions in Myanmar? First, Myanmar would benefit from further export diversification. Sanctions are just one example of an economic shock; natural calamities and political rifts elsewhere in the world also underline the need for diversification. In 2015, 93 percent of Myanmar’s trade was with its top 10 trading partners, out of which China and Thailand together accounted for 65 to 67 percent.

Second, Myanmar must identify products in which it has a relative advantage over other exporters. Pulses might be one such commodity, which would allow for increased exports to India, a major importer of pulses. An excessive focus on rice, for example, is not likely to be beneficial in the long run.

Myanmar should consider ways to integrate itself better with the ASEAN+6 and South Asia in order to cope with such shocks in the future. In this regard, a focus on infrastructure development is key. Finally, Myanmar could encourage research based on hard data to understand economic changes and their impacts nationally, regionally, and globally.

Manmeet Ajmani is a Research Analyst. P. K. Joshi is Director of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) New Delhi office, Avinash Kishore is a Research Fellow at IFPRI, New Delhi. Devesh Roy is a Senior Research Fellow at IFPRI, Washington D.C.