China just made a scientific breakthrough in biomedicine and cloning technology.

On January 24, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) — China’s national academy for the natural sciences — announced that it has successfully cloned not only one but two monkeys by optimizing the method that created Dolly the sheep clone 22 years ago.

Cell, the premier journal of the life sciences, published the full research paper on its website on the same day.

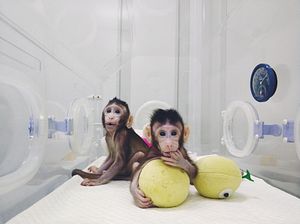

The two cloned long-tailed macaques were born in the Institute of Neuroscience of CAS in Shanghai. They were named by Chinese scientists as Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua; the combination “Zhonghua” means Chinese nation or people.

Xinhua reported that a third genetically-identical monkey will be due this month.

In 1999, U.S. Professor Gerald Schatten of the Oregon National Primate Research Center created the first cloned primate through a cloning technique called “embryo splitting.” This technique’s limit is that it can only generate up to four offspring at a time.

In comparison, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the technique used to create Dolly the sheep in the 1990s, allows researchers to create clones without such limitations. In this process, scientists remove “the nucleus from an egg cell and replace it with another nucleus from differentiated body cells.” The researchers can then develop this reconstructed egg into “a clone of whatever donated the replacement nucleus,” according to CAS.

Ever since Dolly the sheep was cloned by Scottish researchers, many other mammalian species, including mice, cattle, pigs, cats, rats, and dogs, have been cloned with the same technique. But compared to these mammals, nonhuman primates’ cell nuclei have proven resistant to SCNT, CAS said.

China’s researchers have overcome this challenge now. The first author, Liu Zhen, a postdoctoral fellow, spent three years practicing and optimizing the SCNT procedure and tested various methods to quickly and precisely remove the nuclear materials from the egg cell.

“The SCNT procedure is rather delicate, so the faster you do it the less damage to the egg you have, and Dr. Liu has a green thumb for doing this,” says Muming Poo, a co-author on the study, who directs the Institute of Neuroscience of CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology.

Sun Qiang, director of the Nonhuman Primate Research Facility at the CAS Institute of Neuroscience, believes that this breakthrough will contribute to research on genetic brain diseases, cancer, immune or metabolic disorders, and will “allow us to test the efficacy of the drugs for these conditions before clinical use.”

However, some scientists have also raised concern over ethics risks.

For example, NPR quoted Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University, as saying, “People have always been worried about the possibility of human cloning. And this is just yet another step in that direction.”

Noting the risks as well, Muming Poo said: “We are very aware that future research using nonhuman primates anywhere in the world depends on scientists following very strict ethical standards. ”

“That’s why cloned monkey models are valuable, but production also needs monitoring. Any abusive use could cause trouble,” he added, according to Xinhua.