On an almost daily basis in China, the ruling Communist Party and state agencies issue detailed instructions to news outlets, websites, and social media administrators on whether and how to cover breaking news stories and manage related commentary. Although technically secret, hundreds of these directives have been leaked over several years by anonymous whistle-blowers in the media and elsewhere, offering observers unique insight into the party’s information control operations.

It is therefore worrying that the leaks are becoming less common even as the authorities’ censorship ambitions continue to grow.

Drawing on an archive compiled by the nonprofit California-based website China Digital Times (CDT), Freedom House has analyzed over 500 directives in the past four years. The vast majority of them call for “negative” actions, such as deleting an article, not sending reporters to cover an event, or closing a website’s comment sections. But some mandate “affirmative” actions to promote the party line, particularly republishing copy from official news sources.

Freedom House’s analysis of the directives from 2017 reveals five notable trends:

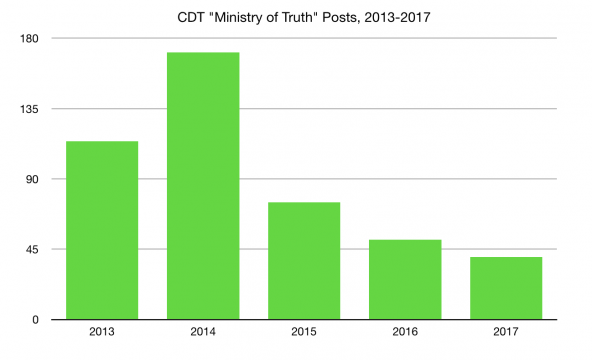

1. A sharp decline in number of leaked directives: In 2013–14, at the start of President Xi Jinping’s tenure, a total of 341 directives were leaked over two years. The figure shrank to 81 in 2015 and 95 in 2016. And in 2017, only 43 directives were leaked. According to CDT founder Xiao Qiang, the drop probably does not reflect a reduction in the number of directives being issued by relevant authorities. Instead, several sources have indicated that sharing them has become “far more dangerous than before.”

Relevant factors behind the increased risk to whistle-blowers — and their new tendency to refrain from citing the official agency that issued an instruction — include tighter newsroom controls on media workers, reduced anonymity in online communications, and punishments of journalists and bloggers believed to have shared confidential information with foreign audiences.

2. Shifting priority topics for leakers, party officials: With many fewer directives available, it is more difficult to draw conclusions from the frequency with which a given news topic appears in the documents. On the one hand, commonly targeted categories of emerging news could correspond to authorities’ greatest fears. On the other hand, as CDT’s Samuel Wade notes in a recent post, the leaked directives may simply reflect the whistle-blowers’ own judgment as to which items were interesting or important enough to risk leaking.

For example, the category that appeared by far the most often in 2017 was health and safety. A total of 15 directives restricted coverage and online discussion of topics including environmental pollution, natural disasters, child abuse, an HIV scandal, and allegedly shoddy high-speed rail construction. Whistle-blowers’ priorities may have also played a role in the frequent appearance of leaked directives in the category of media and censorship, as those working in the news industry would naturally be concerned about this topic. A total of six directives either restricted reporting on the censorship system itself or sought to protect official media initiatives — like the state broadcaster’s annual Spring Festival Gala or the World Internet Conference in Wuzhen — from criticism.

The other two most common categories in the 2017 sample — official wrongdoing and foreign affairs — are more likely to reflect party leaders’ priorities. Six directives restricted coverage of official wrongdoing, including two incidents in which government workers opened fire on others and reports of the abduction from Hong Kong of a billionaire financier with close ties to the ruling elite. Five directives restricted coverage related to foreign affairs, including China’s relations with North Korea, the Philippines, and the United States. In an unusual occurrence, several directives specifically sought to control coverage of U.S. President Donald Trump, with one stating that “unauthorized criticism of Trump’s words or actions is not allowed.”

Three other directives targeted reporting on the reputation of the party or individual officials, including coverage of the 19th Party Congress in October. The small figure represented a drop from 2016, when this was the most common topic in the sample of leaked directives. Also in contrast to 2016, no directives contained orders meant to protect Xi Jinping’s reputation specifically, but this could reflect leakers’ awareness of the heightened sensitivity surrounding his persona.

The remaining directives dealt with topics like sports (a new category that did not appear in past years), civil society, social unrest, Taiwan, and the economy. Only one directive focused on the economy; in 2015, when China’s stock market suffered a major reversal, this was the second most commonly targeted category.

3. Increased focus on mobile apps: The 2017 directives illustrate censors’ efforts to expand their instructions beyond traditional media, websites, and news portals to reach mobile-based news applications and related dissemination methods.

More directives specifically name mobile apps than in previous years, and several cite “self-media” — a term for public accounts on social media — as entities expected to implement the relevant instructions. Some also explicitly direct administrators not to issue “push notifications,” or news alerts sent to mobile phone users, for the relevant story. The terms “self-media” and “push notification” had not appeared in leaked directives in previous years.

This new focus is an adaptation to the growing popularity of mobile applications as a source of news, particularly for many young Chinese. It also reflects the censorship apparatus’s efforts to implement standing orders from Xi Jinping to ensure that the party’s controls reach all forms of media.

4. Emphasis on downplaying hot stories: As an alternative to outright deletion of content, a particularly common tactic — evident in nearly one-third of the directives analyzed — was to instruct editors, web portals, and other content administrators to downplay stories that might otherwise garner significant public attention, or whose popularity may have already exceeded party leaders’ tolerance levels. The methods included generic “don’t hype” orders, bans on special features, and highly specific instructions on the placement of stories.

One leaked directive from January 2017 regarding coverage of the U.S. presidential inauguration ordered that “mobile clients strictly prohibit display on front screens.” Others from the fall address abuse at a daycare center in Shanghai and require that related news “must be moved after websites’ third page” and “taken off front pages.” Compared with other censorship methods, like the deletion of individual users’ social media posts, this kind of behind-the-scenes manipulation is highly effective at killing a story, but also less obvious and less likely to generate resentment.

5. Restricting use of content from state-backed outlets: One of the most surprising trends evident from the 2017 sample is the extent to which the Chinese authorities are nervous even about the circulation of content from official news sources or other publications with close state support. In one stark example, an April 2017 directive regarding self-exiled billionaire and government critic Guo Wengui instructed websites not to forward news on the topic, “including domestic official media reports.” In addition, at least five directives ordered the deletion of stories or content initially reported by The Paper, a state-funded Shanghai-based digital news outlet that was created as part of an official push to win readers from more autonomous commercial media. Such instructions reflect the fact that even media with close official ties have difficulty navigating censors’ ever-shifting red lines.

Given the official investment in time, attention, and resources that these directives represent, it is worth asking how effective they are.

Their implementation is often visible in coverage changes and available research on social media censorship. For example, 2017 data from Weiboscope, a Hong Kong University project that maps censorship on the social media platform Sina Weibo, shows spikes in deletions and flagged keywords correlating to particular censorship orders, including those regarding the medical parole and subsequent death of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo in July, the Party Congress in October, and public outcries over a daycare scandal and mass evictions of internal migrants in Beijing in November.

Yet the content of the directives points to the challenges the party faces in suppressing news stories that are of particular public interest. The directive banning information sharing related to Guo Wengui notes with subtle exasperation that it is the third order on the same topic, indicating that some contingent of recipients were lax in implementing censorship on one of the hottest stories of the year. Similarly, the need in November to issue a second directive barring coverage of the daycare abuse scandal that erupted in September signifies that the story had not been entirely quashed.

The fact that dozens of directives continue to be leaked each year — particularly on news related to public health and safety — also demonstrates that some people within the system remain exceedingly uncomfortable with the party’s censorship efforts, and are willing to take great risks to expose them.

Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst at Freedom House, director of its China Media Bulletin, and author of the “Battle for China’s Spirit: Religious Revival, Repression, and Resistance under Xi Jinping.“ Alexander Lin provided research assistance.