“Who won and who lost in the great Tet Offensive against the cities?” Walter Cronkite asked his audience in February 1968. “The Viet Cong did not win by a knockout, but neither did we. The referees of history may make it a draw.”

Today, the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, a unanimous decision has not yet been reached. Even the very nature of the insurgent “Viet Cong” has eluded the referees of history. Instead, most remain locked in two competing camps of Orthodox and Revisionist scholars. Their opposing interpretations of the term “Viet Cong” are at once a symptom of the larger battle for the meaning of America’s war in Vietnam, but also a means to transcend that dead-end debate.

The War for Vietnam’s History

The Orthodox school is familiar to anyone who has taken a college course on the war or read Pulitzer Prize winners like Frances FitzGerald’s Fire in the Lake or Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie. In the years after the Tet Offensive, anti-war scholars believed they could mobilize history to oppose what they saw as s a misguided if not immoral war. General William Westmoreland was not fighting the Viet Cong, so the Orthodox argument went, but rather the march of history: an innate Vietnamese resistance to foreign occupation and peasant nationalism embodied in Ho Chi Minh. That North Vietnam or its leaders were communist didn’t feature all that prominently in such narratives, nor that their ambitions were opposed by a great many other Vietnamese.

In time, a Revisionist rebuttal emerged, using its own troublesome reading of Vietnamese history to rehabilitate the U.S. war effort. For many Revisionists, the U.S. war was a noble pursuit and sure of victory, if not for the incompetence of William Westmoreland or the meddling of Saigon’s press corps.

Like the war at large, the origins of the “Viet Cong” have been distorted by each school. From Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie to Christian Appy’s more recent American Reckoning, the term “Viet Cong” is portrayed as the result of American duplicity and arrogance, defining attributes that they would also diagnose in the Tet Offensive. These authors tell readers that “Viet Cong” — meaning “Vietnamese communist” — was a pejorative term invented by officers of the United States Information Agency. By so branding the broad nationalist insurgent forces in South Vietnam as communists, these Orthodox scholars argue, Washington was guilty of transforming a local colonial conflict into a Cold War battlefield. For Revisionists, Viet Cong is a fitting term that illustrates Russia, China, and North Vietnam’s control of the insurgency.

Viet Cong and the Chinese Origins of Vietnam’s Long Civil War

The origins of “Viet Cong,” like those of the Vietnam War, are not found in America’s Saigon embassy. They lie instead in the 1920s and 30s. Its true origin illustrates how Vietnamese internationalized and initiated their own civil war, long before the arrival of the U.S. military.

Vietnamese revolutionaries had often fled to southern China to escape the French colonial state. By the late 1920s, both Vietnamese communists and nationalists sought refuge and military training in Sun Yat Sen’s Republic of China and the famous Whampoa Military Academy. Ho Chi Minh, recently returned from the Soviet Union, was here alongside leaders of the Vietnamese Nationalist Party like Vu Hong Khanh. For a time, each group of Vietnamese cooperated among themselves, and with their respective Chinese ideological allies during this period of cooperation between Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of China and Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist Kuomintang.

Vietnamese accessed Chinese translations of European political theory and adopted new ideas from their neighbors. Imbued with the concept of nationality in the 1920s, Vietnamese revolutionaries also learned the concept of a hanjian to denote a “traitor to the Chinese Han race.” They likewise learned the term zhonggong, used by all as shorthand for the “Chinese communists.”

By the end of the decade, the fragile entente between the Chinese communists and Kuomintang had given way to the Chinese Civil War. Their Vietnamese compatriots took to respective sides, thereby giving rise to a low-scale Vietnamese civil war between members of the Stalinist Vietnamese Communist Party and the Vietnam Nationalist Party that would linger through the 1930s.

These rival Vietnamese factions would battle for influence in northern Vietnam and southern China, where each party spied upon the other and on occasion authorized assassinations of suspected infiltrators. Even the aged revolutionary Phan Boi Chau — remembered today in Vietnam as a hero second only to Ho Chi Minh — sided with the Vietnamese Nationalist Party in this civil war. “Those who exploit socialism,” Phan Boi Chau declared in the newspaper Trang An Bao in 1938, “do so to split the ranks of the nation, to destroy our unity, and to annihilate our peoples’ national spirit.” In response, the future General Vo Nguyen Giap and communist General Secretary Truong Chinh denounced Phan Boi Chau in their newspaper, Notre Voix, as a traitor.

The battle between the ICP and Nationalist Party was not at its fiercest in newspaper columns, but rather inside the colonial prison system. A copy of the Nationalist Party’s 12-point 1935 platform, discovered in Hanoi’s prison, listed the party’s first two goals as raising awareness of the Vietnamese nation and eliminating communism. On penal island Con Dao, this intense ideological conflict led to deadly fights. “The cool ocean breeze on Con Dao.” the future North Vietnamese leader Tran Huy Lieu recalled, “could not dissipate the smoldering atmosphere that enveloped the island.”

1945: Vietnam’s Civil War Reemerges

When the Vietnamese revolution began in August 1945, those tensions had not dissipated. For a time, Ho Chi Minh’s revolutionary Viet Minh state held together a unity cabinet with Stalinist members of the communist party and nationalist leaders like Vu Hong Khanh. Within months the entente collapsed. Both sides reprised the Chinese term hanjian to target ‘Viet gian’ (traitors to the Vietnamese race) and reverted to a bloody civil war, long before the official start of French Indochina War in December 1946. Troops loyal to Vo Nguyen Giap and the communist faction of the Viet Minh attacked units affiliated to the Vietnamese nationalist parties, forcing them to flee to China in defeat.

When war broke out later that year between Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh state and France, those exiled nationalists groups pledged to open their own negotiations with France. United under the former emperor Bao Dai — who had served as a counselor to the Viet Minh state before also fleeing into exile — they pledged to work with France to gradually obtain independence through peace and cooperation.

Their terms of cooperation included a Vietnamese government that was not beholden to the Stalinist leadership that had seized control of the Viet Minh state. As negotiations dragged on with France, these nationalist organizations grew worried about the Chinese Civil War. Mao Zedong’s communist forces were nearing the Vietnam border and would assist the Viet Minh state. Nationalist parties reprised zhonggong, the Chinese term they had learned in 1920s and literally translating to “Trung Cong” in Vietnamese — “Trung” meaning “Chinese,” and “Cong” meaning communist. By the 1940s, the term was already familiar to Vietnamese readers.

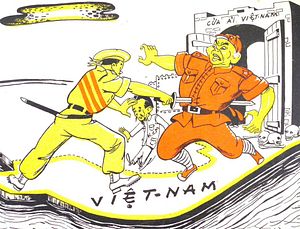

By 1948, nationalist newspapers like Tieng Goi began to speak of a new term: Viet Cong. Tieng Goi warned, “If this Viet-Cong army is able to joins hands with the Trung Cong at the Sino-Vietnamese border, then what more can prevent the communization of Vietnam?” In this way, the nationalist parties linguistically linked the Chinese communist Trung Cong to their Vietnamese counterparts the Viet Cong. If the term was pejorative at its origin, it was only insofar as it linked the Vietnamese to China. The nationalists, for their part, became known in the same convention as “Viet Quoc” — literally “Vietnamese nationalists.”

A Rival Non-Communist State

The following year, former emperor Bao Dai and the nationalist parties would agree to form the non-communist, French sponsored State of Vietnam. In the latter part of the French Indochina War, the State of Vietnam controlled roughly half the population and the urban centers from Hanoi south to Saigon. More Vietnamese died in service of this state than did Frenchmen for their empire. As Stalinists seized leadership of the Viet Minh and began to remake it into a party-state, implementing Mao Zedong’s prescribed style of land reform, the State of Vietnam increasingly used “Viet Cong” in official communications to denounce the communist leadership of the Viet Minh.

The 1954 Geneva Accords would soon divide Vietnam in two — the south administered by the State of Vietnam, soon renamed the Republic of Vietnam or South Vietnam, and the north by the Viet Minh state now known as North Vietnam. By the end of the 1950s, members of the Viet Minh and communist party began an uprising in the south and North Vietnam resolved to support and lead this southern uprising. South Vietnam, under the leadership of President Ngo Dinh Diem, denounced these “Viet Cong” insurgents. American special forces and journalists would soon arrive in Saigon, taking up the same term of reference for the southern insurgent forces in the countryside and their North Vietnamese supporters.

Contrary to some histories, the term “Viet Cong,” like the war itself, was not a byproduct of the American presence in Vietnam, even though the American presence greatly shaped events. Instead, it originated in a longer Vietnamese civil war between rival political parties vying over the control and character of Vietnam’s postcolonial state. It was Vietnamese themselves who began the internationalization of their war, by incorporating themselves literally and rhetorically into the Chinese Civil War and the early stages of Asia’s Cold War.

Brett Reilly is a PhD Candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison specializing in Southeast Asian history and the global Cold War. In 2016 he was a Fulbright-Hays Fellow in France and in 2015 a Boren Fellow in Vietnam.