The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led Indian government on Thursday presented the annual budget for the country, which is the political party’s last full-fledged budget ahead of the general elections next May.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley presented the budget, which is seen as focused on an agricultural economy while simultaneously seeking political mileage eyeing the polls. Jaitley rolled out highs and lows for each sector. But for people with disabilities, this budget seems to be delinked from laws, programs, and promises.

Every year, objections are raised over India’s disabled citizens having received a raw deal. But a confluence of convoluted factors leading up to the 2018-19 budget are making activists and the disabled indignant that this budget is the least inclusive in recent times. This is the first budget presented following the landmark Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 and not much headway can be reported since the passing of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, (RPDA) 2016. These laws were enacted to protect the rights of the disabled and meet international obligations, but the budget makes no mention of financial allocations to implement them.

In his two-hour budget speech, Jaitley emphasized a robust vision for transport infrastructure and healthcare, but he did not cover the differently-abled in this account. The budget spoke of persons with disabilities only in two references — as one of the target groups for a social protection program and while talking about a standard deduction on income tax for the salaried class in lieu of a travel allowance.

India has a long way to go to be a disabled-friendly country in terms of both infrastructure and the discriminatory mentality which its 27 million disabled people are subject to every day. So the budget plays a crucial role in improving their quality of life in availing their right to basic services.

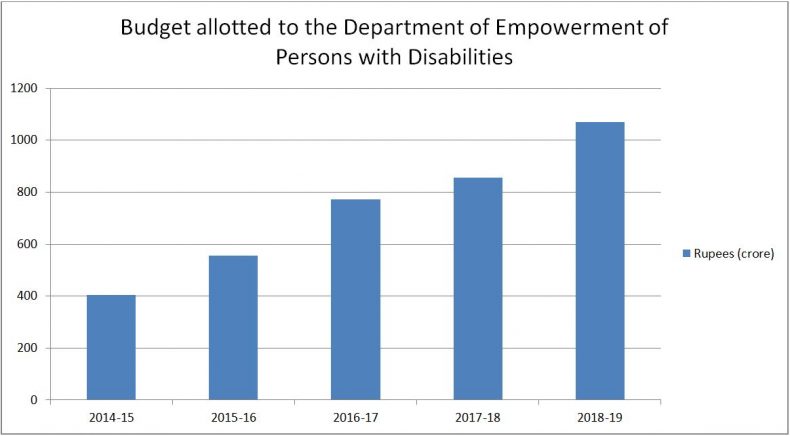

The overall allocation made to the department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment) is a marginal increase from 855 crore rupees ($132 million) last year to 1070 crore ($166 million) this year. “Where is the money to implement provisions in these legislations? It’s almost as if these two Acts were never passed,” says Amba Salelkar, a lawyer with Equals, Center for Promotion of Social Justice, an organization focusing on policy and budget advocacy toward furthering the rights of persons with disabilities.

After several years of advocacy, a key advancement pushed in the recent RPDA, 2016 (which replaced the erstwhile Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995) is an increase in the various types of disabilities officially recognized by the government from seven to 21. The list now includes those with a speech disability, autism, acid-attack victims, and more. “The budgetary allocations [aren’t] commensurate [with] the increase in categories, which is baffling,” adds Salelkar.

In the finance minister’s headline-making flagship scheme of the “world’s largest government funded healthcare program” for 100 million poor families or 500 million individuals and in allocations made for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, there are opportunities missed. According to an analysis by the Delhi-based Center for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), there is a lack of specific allocations toward the availability and accessibility of health services such as sexual and reproductive healthcare, prevention of secondary impairments, and health insurance, which is mandated by RPDA, 2016.

“The Mental Health Care Act mandates transition from institution to community living for persons with psychosocial disability. However, the analysis of the health budget presents a decreasing trend in allocation for persons with disabilities, not adhering to the prescribed norms of this Act,” their report added.

Jaitley also announced an “all-time high allocation to rail and road sectors,” but there is no clarity if these funds will be used to make transportation accessible. In previous budgets, 500 accessible railway stations and wheelchair-friendly toilets were announced. But there were no such specifics or updates tabled this time for those whom this government ostensibly renamed “divyaang,” meaning divine body. Following Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s suggestion, official documents and government bodies began changing the nomenclature in Hindi from “viklang” (disabled) to “divyaang,” causing an outcry among the community, which opposed the idea of human diversities being identified as divine.

The lack of disabled-friendly public infrastructure has left many of them dependent on their families or restricted their commute. Those who can afford the expense modify their cars and two-wheelers to suit their disabilities and are independent. However, this is a small number compared to the thousands of people with locomotor disabilities or visual and hearing impairments, who depend on buses or trains, where they are prone to minor accidents and falls, for their daily commute.

“Disabled people in this country are already segregated and discriminated. Without accessible transport facilities, we simply do not get to go out of our homes,” says Viral Modi, who started the #mytraintoo campaign, which marked a major impact in India. Her advocacy started as an online petition at Change.org after she was sexually molested while being carried on her wheelchair to board local trains. The Mumbai-based activist has since worked with railway officials for accessible transport and recently the Ernakulam Junction in the southern state of Kerala constructed disabled-friendly infrastructure following her campaign.

Viral Modi (no relation to India’s prime minister) is one of those disappointed with the recent budget. “This budget takes all our effort backwards,” she says. “People with disabilities need to be mainstreamed and deserve to live with dignity. We are tax payers too and there is nothing done for our benefit. The government also needs to realize that if they make transport and infrastructure accessible, there will be a significant increase among tourists with disabilities and medical tourism.”

The budget has made an additional allocation of 3 billion rupees ($46.6 million) to a Scheme for Implementation of the Persons with Disabilities Act (SIPDA), which was formulated under the old 1995 disability legislation for state governments to access grants to make public buildings barrier-free. The CBGA analysis observes that though this allocation sees an increase of 16.7 percent, the funds are also directed toward the Accessible India Campaign, launched by Prime Minister Modi in 2015. Activists say that this dilution of funds is problematic as this flagship campaign excludes a majority of rural areas where people with disabilities live. Data collected from this campaign pointed toward an infrastructure deficit but that information has not been made available.

Last year, the Press Information Bureau, a government agency, released a statement that by March 2018, under the campaign, all international and domestic airports will have ramps, accessible toilets, and lifts with braille and auditory signals, and that ten percent of government-run transport will be fully accessible. There was no mention of the progress made toward these targets. There is also no allocation made for the disability survey committed to in the government’s policy think tank NITI Aayog’s three year action agenda. Despite constant demands for raising pensions for the disabled, allocations made under the Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme remain unchanged.

“The campaigns are eyewash and this fiscal management is not being done as a right but merely as charity,” says Deepak Nathan, founder of December 3 Movement, a pan-India rights-based organization.

“It seems as though the disabled do not figure in the finance minister’s fast growth economy,” the Delhi-based National Platform for the Rights of the Disabled said in a statement. “The financial implications [are] not present in the Act and it is expected from the budget but there is lack of sincerity form the government to implement the provisions of the Acts which they passed,” says the organization’s general secretary, Muralidharan V. “These are miserly outlays for the disabled community who continue to live in the margins.”

“Since so many ministries are involved in rolling out initiatives for the disabled, we never know the quantum of how much is being allocated for the disabled community,” he says, urging a separate section in the budget. For instance, the department of school education, which functions under the Ministry of Human Resource Development, includes children with disabilities as their target group, but there is no disaggregated data of allocations made specifically for them.

Following the union budget, every state government also presents an annual budget, which makes detailed provisions for people with disabilities. “Though disability is a state subject, several of its schemes are primarily funded by the central government,” says Salelkar. Yet in this budget, she adds, “There was no mention of mental health, suicide prevention, rehabilitation, and accessibility for people with disabilities from rural areas. The budget should have also looked at strengthening existing programs. It was very disconcerting and without enough budgetary allocations, we do not know where we are headed.”

Divya Chandrababu is an independent journalist, based in Chennai, who is a recipient of the Press Institute of India-Schizophrenia Research Foundation’s (SCARF) award for outstanding reportage on mental health.