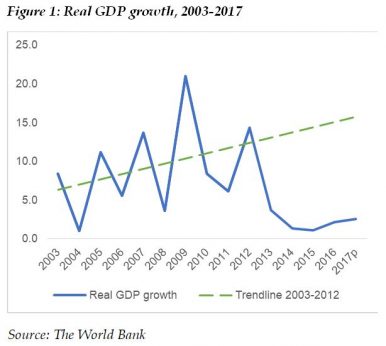

Afghanistan experienced remarkable economic growth for about 10 years leading up to 2012. Average economic growth was recorded at 9.4 percent annually in the period from 2003 to 2012. Per capita income increased more than threefold over the same period, growing from a mere $200 to $670. Since 2012, however, economic growth has dropped to an average yearly rate of 2.6 percent, with per capita income falling to an estimated $590 in 2017. As a result of this economic slowdown, the poverty rate increased from 36 percent in 2011-12 to 39.1 percent in 2013-14. The World Bank expects that poverty will prove to have further sharply increased through 2017, though the results of the latest household survey (2016-17) are yet to be released by the government.

The period from 2012 to 2014, which marked a turnaround in the economic performance of the country, coincided with a number of important developments. First, security responsibilities were transferred from international security troops to Afghan forces. This security transition started in 2012 and concluded in 2014. Second, as a result of the security transition, overall foreign aid is estimated to have declined from an annual average of $ 12.5 billion over 2009-2012 to around $8.8 billion in 2015. Third, a political transition also took place in 2014, where the election process leading to the establishment of the National Unity Government lasted for about six months.

While the decline in foreign aid since 2012 may have well contributed to the slowdown in economic growth, it’s not the only factor. The low economic recovery since the conclusion of the security and political transition in 2014 seems to be suggesting that political developments are exerting a substantial impact on the economy.

Indeed, the political environment influences economic decisions and outcomes through different channels, one of which is the channel of political uncertainty and instability. Political instability makes future economic outcomes uncertain, and therefore businesses reduce their investment in light of uncertain returns and high risks and consumers increase their precautionary savings to seek insurance against future risks leading to lower consumption. As a result of lower investment and lower consumption in the aggregate economy, domestic demand weakens and economic growth may decline.

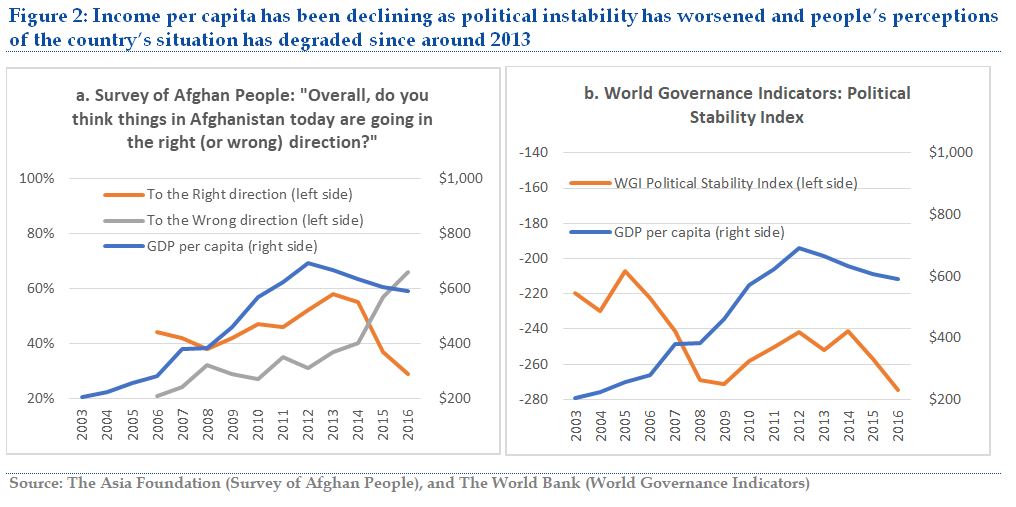

Perception and composite indicators show that political instability and uncertainty have heightened in Afghanistan since around 2013. The Survey of Afghan People indicates that the percentage share of people who are optimistic about the country’s situation has fallen since its peak in 2013 to a record low in 2016 (see Figure 2a). Likewise, the percentage share of people who think that things in the country are going in the wrong direction has increased since 2013 reaching a record high in 2016. Though these two indicators show the public’s perception of the current state of affairs, they also reflect the public’s confidence in future outcomes. A decrease in public optimism (or increase in public pessimism) reflects increased uncertainty in the country. Further, the Political Stability Index of the World Governance Indicators has fallen to the lowest level since 2003 (Figure 2b).

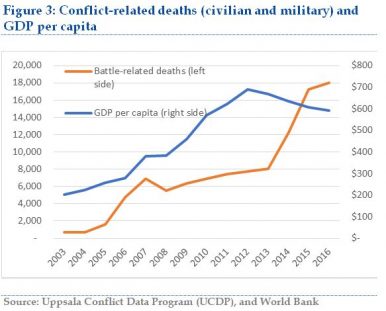

Increased perceptions of political uncertainty have persisted as the security environment has deteriorated since 2014. The number of conflict-related deaths, including both civilians and military personnel, has rapidly risen since 2013, reaching a record level in 2016 (Figure 3). A deteriorating security environment has prevented business and consumer confidence from being restored since the conclusion of the transition process in 2014. Recent political disputes do not help, instead fueling uncertainty. Moreover, as the public forms expectations based on their experience with past similar events, the upcoming presidential elections will keep the fire burning until then. Uncertainty will likely persist until a successful and swift conclusion of the next presidential elections in 2019, which could lead to a turnaround in the security environment. It will take a single, strong positive shock to end the public’s persistent pessimistic expectations.

Against this ongoing uncertainty, what should realistic expectations about economic growth look like? And would it be possible for Afghanistan to retain the levels of economic growth experienced in the pre-transition era?

How Does Uncertainty Affect Economic Growth?

Uncertainty affects aggregate economic performance through changes in people’s confidence and behavior. Going as far back as the 1920s, the renowned economist Arthur Cecil Pigou suggested that business cycles (i.e. booms and busts in economic growth) are driven by people’s expectations, which result from psychological causes. John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, rhetorically used the word “animal spirits” to refer to the decisions of people at times of uncertainty. He argued that “animal spirits” guide the confidence, fear, and pessimism of people, which affect their decisions of consumption, investment, and saving. Waves of optimistic or pessimistic expectations about the future influence the behavior of individuals. Confidence or lack of it can therefore drive or hamper economic growth.

Uncertainty may refer to political and/or macroeconomic uncertainty. “Uncertainty” is defined as people’s inability to forecast the likelihood of events happening. Thus, it may refer to both uncertainty around political events and uncertainty around macroeconomic outcomes. Uncertainty almost always comes about with “bad news.” Empirical studies have identified that uncertainty shocks are almost always associated with news that is perceived to lower expected growth or to exacerbate political instability. For instance, the agreement on the international troops’ withdrawal from Afghanistan was perceived as “bad news” by the people, which seem to have increased uncertainty in the country.

The economic literature confirms that uncertainty adversely affects economic growth. A number of empirical studies have found that the impact of uncertainty on growth is quite substantial. For instance, one study estimates that in the year leading up to an election, when political uncertainty heightens, firms reduce investment by an average of 4.8 percent relative to non-election years. Another study found that increased political instability – proxied by turnover in 50 percent of cabinet posts – reduces the annual real GDP per capita growth rate by 2.4 percentage points. Another study distinguished between those regime changes which are followed by mass protests and those that are not, and found that regime crises accompanied by mass civil protest cause an immediate drop in output, which, on average, is not recovered in the following five years. These studies also found that the impact of uncertainty and/or instability on economic outcomes is more pronounced in countries with less stable political systems and weak institutions.

Uncertainty is more pronounced and more frequent in developing and poor countries, where political instability is much higher due to higher frequency of political shocks like coups and wars, and the quality of institutions is poor. Further, macroeconomic uncertainty also seems to be more pronounced in poor countries due to their higher vulnerability to shocks.

Uncertainty affects economic growth through three main channels. First, uncertainty around future returns to investment may delay investment decisions by firms. Uncertainty makes firms cautious about investment and hiring decisions, which are usually difficult to reverse due to high adjustment costs. Uncertainty also increases risk premiums, which in turn increases the cost of finance and discourages new investments. This is particularly important in countries that are financially underdeveloped and where firms do not have easy access to finance.

Second, uncertainty leads to postponed consumption. When uncertainty around consumer income or market conditions is higher, consumers delay their consumption decisions and instead increase their precautionary savings. Consumers can delay their decisions of purchasing durable goods such as housing, cars, and equipment relatively easily. In the short-run, the effects of lower consumption is contractionary for an economy. In the long run, however, the effects of lower consumption and higher savings is less clear, depending on the extent to which savings are intermediated domestically to support private investment and on the weight of household consumption in the economy.

Third, uncertainty may lead to increased rent-seeking behaviors, particularly in institutionally weak countries. Rent seeking, corruption, and capture of resources intensify when uncertainty associated with an unstable political environment heightens. As perceptions of political instability increase and individuals see uncertain income in the future, incentives for capturing rents increase. Rent seizing leads to misappropriation of resources and therefore reduces economic growth.

The first two theoretical channels explained above not only suggest that uncertainty reduces the levels of investment, hiring, and consumption, but it also makes economic actors less sensitive to changes in business conditions. This makes countercyclical economic policy less effective. For instance, some empirical studies have found that the impact of fiscal spending on output (i.e. the size of fiscal multipliers) is larger in periods of tranquility than in periods with higher uncertainty. They explain that “confidence” plays an important role in explaining this differential impact. Further, higher uncertainty makes consumers’ spending on durable goods less sensitive not only to demand and price changes but also to tax cuts.

Therefore, higher uncertainty makes fiscal and monetary stabilization instruments less effective. While in low-income countries, the monetary policy transmission channels are already weak, and fiscal policy is the only instrument at the hands of governments, the effectiveness of government expenditures also declines when uncertainty is higher. The effectiveness of economic policy is further reduced if “policy instability” – meaning frequent reversals in government policies – emerges with increased political instability. If the public lose their trust in the messages and signals they get from the government as a result of frequent reversals of policy measures, then the effectiveness of public policy is significantly reduced.

How Has Uncertainty Affected Investor Confidence and Rent-Seeking Behavior in Afghanistan?

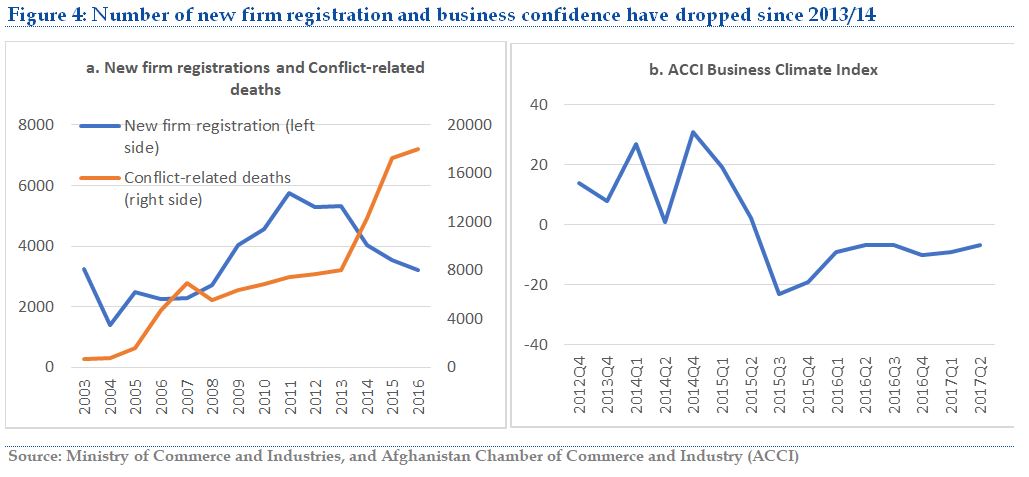

As political uncertainty and instability heightened in Afghanistan around 2014, both household consumption and private investment declined, leading to lower domestic demand. The average annual growth rate of domestic demand declined from 11.5 percent in 2009-2012 to 1.8 percent in 2013-2016. Proxy indicators for private investment, such as the number of new firm registrations, showed a drop in new investment activities after 2013. Business confidence collapsed, with no signs of recovering so far to pre-2014 levels. In sum, uncertainty has substantially limited private investments. Though it is difficult to differentiate the impact of uncertainty on investment from the effects of lower growth in a vicious investment-growth cycle, one can comfortably say that increased uncertainty around 2014 did put significant pressure on investment in the country.

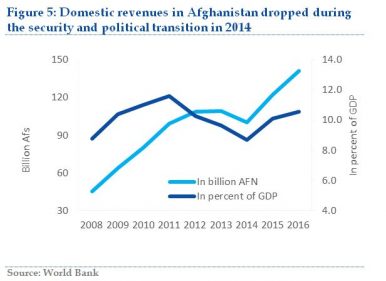

Uncertainty may also lead to increased levels of corruption and higher risks of rent-seeking by vested interests in the government. This effect of uncertainty on corruption and rent-seeking in Afghanistan can be substantiated through the revenue collection performance of the government during the transition period. Domestic revenues declined by around 9 percent (in “nominal” values) or equivalent to around 1 percentage point of GDP in 2014 as uncertainty around the security and political transition heightened in the country. Weaker economic activities or lower imports in 2014 could not fully explain the 9 percent decline in fiscal revenues; some part of the revenue decline was likely due to capture by those with vested interests in the government.

Uncertainty may also lead to increased levels of corruption and higher risks of rent-seeking by vested interests in the government. This effect of uncertainty on corruption and rent-seeking in Afghanistan can be substantiated through the revenue collection performance of the government during the transition period. Domestic revenues declined by around 9 percent (in “nominal” values) or equivalent to around 1 percentage point of GDP in 2014 as uncertainty around the security and political transition heightened in the country. Weaker economic activities or lower imports in 2014 could not fully explain the 9 percent decline in fiscal revenues; some part of the revenue decline was likely due to capture by those with vested interests in the government.

Conclusion

Uncertainty suppresses business sentiments and affects consumer confidence. The uncertainty that has been built up since the start of the security and transition process in 2012 and has subsequently been fueled by growing insecurity has significantly lowered economic growth in Afghanistan. It seems that the high growth experienced prior to 2014 will likely be difficult to achieve, unless the security environment improves and political stability is strengthened.

Economic policy at times of political uncertainty is often ineffective, and does not lead to desired outcomes. Thus, a policy response in dire economic situations does not remain limited to only pure economic policy measures but should also include political resolutions and initiatives. Decisions which lead to exacerbating political instability must be avoided. Rather than investing political capital into decisions that weaken political stability and increase uncertainty, it should be invested into policy initiatives that help restore confidence in the economy.

Further, it is important that the government maintain realistic expectations around what and how much it can do to bring about growth, generate employment, and reduce poverty. The government needs to ensure that policy measures are designed based on realistic projections for economic growth, rather than overly optimistic growth forecasts. This helps policy measures achieve their expected results, and ensures that economic management remains sound and effective. It may also help avoid unintended adverse distributional impacts of policy measures. Finally, communicating realistic growth expectations and delivering achievable promises to the public would help build credibility for public policy. Credibility is found to be the single most important factor for the effectiveness of economic policy.

However, recent political decisions and initiatives undertaken by the government, unfortunately, defy these principles. If the aim is to strengthen economic recovery and reduce poverty, it would not be possible to achieve these as long as the government sees economic and political spheres in a dichotomy, and political decisions are made while ignoring their repercussions on the economy through the channel of political uncertainty and instability. In this case, any promise to get the economy back to high levels of growth will be nothing but elusive.

Dr. Omar Joya is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the American University of Afghanistan.