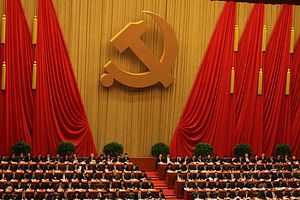

Perhaps we should be concerned. Going around China in the final week of the National People’s Congress, things seemed eerily orderly and calm. Years of heavy investment in high-speed trains mean you can travel like lightning between Beijing and Shanghai, Shanghai and Hangzhou, Xian and Kunming, in ways that were simply unimaginable in the past. The orderly sound of words in newspapers and the images on television supplement this sense of a country that has become a predictable machine. Xi Jinping’s election, unopposed, to the presidency for the second time was described in the People’s Daily in beatific terms, like the canonization of a saint. The images on CCTV supplement this – smiling attendees at the grand meeting in the capital, all looking like they are overwhelmed with happiness and contentment.

Is this the often scrappy, contentious, difficult place I used to travel around two decades ago, where even a 10-minute walk out of the hotel threw up a hundred images and different encounters suggesting a country rich in tensions, competing stories, and sometimes outright conflict?

Looming over everything is the Anniversary. Not that it is spoken about explicitly – yet. But the 100th year of the Communist Party’s existence in 2021 is going to be a big moment – perhaps the biggest ever for the People’s Republic. The 2008 Olympics in Beijing, or the 2016 G20 summit in Hangzhou, were marking points along the way. But 2021 is not just about celebrating a political organization for having existed for a certain amount of time. It is about the rejuvenation, the resurrection, the restoration to justice of a country after a modern history spent as a victim and underdog. In 2021, China will be able to proclaim that against all the odds, it won the battle of modernity on its own terms, in its own way. It will be an intoxicating moment.

The way things are gearing up to this vastly important event, though, has an eerie similarity to the situation that the novelist Robert Musil describes in parts of his great masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities, in which he describes the “Parallel Campaign” to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Franz Joseph as emperor of Austria by 1918. Part of this involves a plan for a Year of Peace and an Austrian Year. Readers of course know as they peruse the accounts of meetings, events, and preparations how this ended — tragically, with assassination, death, and the First World War, along with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire. That gives Musil’s work the quality of a lament, a celebration of an age which was highly optimistic and excited, even while containing the seeds of its own destruction.

It would be stretching things to say that China now occupies the same position as the Austro-Hungarian empire did in the first decade of the last century. Xi Jinping is no Franz Joseph. Even so, the Communist Party itself has been like a domestic empire and has become in some ways almost like an imperial figure in its own right. Under Xi, of course, it has been rejuvenated, and retooled. But if Chinese leaders are not complacent about the Party simply sitting on its laurels rather than seeking new sources of legitimacy and power, nor should we be. At the moment, the CCP is getting rich returns for mining the theme of nationalism, and emphasizing its complete necessity as an entity that will deliver to the Chinese people a great, powerful nation. But it is also haunted by the same intimations of mortality that other dynasties had to deal with. What, after all, will be the Party’s role when the great powerful country it promises actually exists? When the CCP has delivered what it promised it would, what then for it?

Up to 2021, the powerful forces of pride and national feeling will be allowed to flow. The Party will put on a performance of unity and success the like of which it, and the world outside, has never seen. It will make Musil’s “Parallel Campaign” look tame. That will present a misleading veneer. It will make people forget that the same deep structural challenges that we knew existed in China before this moment of confidence and rejuvenation — issues centered around sustainability, inequality, environmentalism and viable unity — are still there, and still need answers.

Among the toughest of these questions is the one that was simply not talked about at the National People’s Congress this year: the country’s political future. We have heard much about what Chinese leaders say they don’t want for their country – no parliamentary bicameral systems (too divisive), no divisions of powers (too fragmenting), no federal system (too risky). But for what they want, we have only heard that it will be “democracy with Chinese characteristics.” It is likely that this phrase above all others will be the one most urgently addressed in the coming few years. The simple fact is that, for all the celebrations that are being planned by 2021, the Chinese leaders will need to have political answers once the jubilation has ended. And even while planning the grand events and public parties, it is likely that this issue is on their minds more than anyone would ever suspect.