Trans-Pacific View author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Jacopo Maria Pepe – Associate Fellow at the Robert Bosch Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia and adviser to the Italian Foreign Ministry – is the 129th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Explain the essential dynamics in the triangular relationship of China, Germany, and Central Europe.

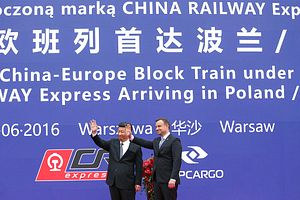

This unusual triangular relationship has essentially a geoeconomic character. It roots in long-term intra-European transformations, which predate China’s engagement in Central Europe. In the past 15 years the economic and manufacturing gravitation center of the EU shifted from Atlantic to Central/Continental Europe. Here, German companies have integrated at different levels many of the economies of Central Eastern European EU-members, especially the Visegrad (V4) countries [the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia], in their value and supply chains. Hence, a regional production network largely dominated by Germany has emerged. Against this backdrop, China’s more recent, active engagement in the Central European production and transport network in the framework of both the 16+1 forum and the BRI [Belt and Road Initiative] has geopolitical implications. Capitalizing on the political tensions between Germany, the EU, and the V4 countries, Beijing is in fact actively transforming this originally regional production network based on the German-V4 bilateral relationship into a transcontinental one, based on a triangular relationship. Germany and China, two major manufacturing powers, might end up both sharing and competing over this joint production space and over its geopolitical orientation.

Why is the China-Germany relationship integral to the EU Asia strategy?

Because the German-Chinese relationship can be considered paramount for EU-Asia relations. Germany and China are the economic powerhouses at the opposite ends of the continent. As pivotal powers in their respective regions, they are drivers of the Eurasian reconnection. When it comes to Asia, China’s rise and activism and the BRI monopolize the strategic discourse in Europe and in Germany. On the other side, given Germany’s preeminent role in the EU and its strong ties with Beijing, German-Chinese relations condense both risks and chances widely shared by most of the EU members, when it comes to China. This is the reason why China is singled out in the EU’s Asia strategy. The flip side of this is, however, that any Asia strategy risks ending up being too China-centered or too China-responsive and less focused on the role other crucial Asian powers like Japan and India can also play for Eurasia’s integration. Europe needs indeed a specific Eurasia strategy which goes beyond China.

How does China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) increase Chinese leadership across Eurasia?

The BRI indeed has the potential to increase Chinese influence across the continent. In fact, it is the only clear attempt to develop a global vision for the next 20-30 years. However, China has no historical experience outside its own region; its actions often cause distress and its ambitions are not always clear communicated. For the BRI to become a true instrument for China’s leadership across Eurasia, concrete trust building measures, better communication, reliability, and accepted, common standards are needed. This said, we should not forget that while China has been wise enough to formulate its own vision with a sound economic logic, the reconnection of Eurasia is historically not a task for one single power. And other Asian and Eurasian powers like Japan, India, and Iran will in the next decades play a crucial role in this process.

How might China leverage fault lines in the divergent views of Hungary and Poland vis-à-vis the EU?

China is not only taking advantage of the geoeconomic fault lines that have emerged in the past 10-15 years inside the EU, between Central Europe, including Germany and the Visegrad countries on the one side and the Atlantic and Mediterranean ”periphery” on the other side. China can now also capitalize from new political fault lines that have emerged since 2015 with the migration crisis. Politically the conservative-nationalist governments of countries like Hungary and Poland oppose Germany, France, and other Western European EU members as well as the EU institutions. Capitalizing on the promises of major investments and on its silent inroads into Central Europe, Beijing could present itself as a less complicated partner, acting as external balancer to both Germany and the EU and indeed leveraging this relation to influence the intra-EU decision making process. From the point of view of Germany, geoeconomic and geopolitical consideration should indeed lead to a normalization of the relations with the Visegrad countries and to a coordinated approach toward China, to avoid [the possibility] that Beijing or other external powers could further gain from these “double fault lines.”

Should the U.S. administration be concerned about China’s BRI as a potential platform for Eurasian integration?

The U.S. administration should come to terms with the BRI. Doubtless, the BRI bears both risks and chances for the U.S. But Washington should escape its “Eurasian dilemma” between disengagement or containment. It should find a way to proactively and pragmatically engage with China on some common issues like the fight against the terrorism and the radicalization of Central Asian societies, the stabilization of Afghanistan, trade facilitation, better connectivity, international investments in common goods like transport, power grids, social infrastructures. There is a sound logic behind all this. Meanwhile, Washington should actively participate and invest, along with other partners like Japan or India, in successfully developing alternative and complementary projects like the Southern Corridor. Moreover, the U.S. should look very carefully at any potential split in the Chinese-Russian relationship. Eurasia Integration is not an exclusively Chinese phenomenon and it is not only driven by the Russian-Chinese entente.