A Pew Research Center study found that China’s favorability is rising with other nations. One way China achieves this in Africa is through public medical aid.

Chinese medical support in Africa dates back half a century — in 1963, China sent 100 healthcare workers to assist Algeria after it gained independence from France. However, the level of involvement has been increasing in the past decade.

In 2006, at the third Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), held in Beijing, Chinese and African officials introduced measures to broaden bilateral cooperation, including medical care and public health. The Chinese spent an estimated $35 million on health-related projects in Africa in 2006. By 2014, they were disbursing an estimated $150 million annually. Chinese parties build health facilities, donate supplies, grant funds, and provide staff.

Although China’s federal government provides support, actual projects are carried out at local levels. China uses a “province to country” model – individual provinces provide aid to one or more sister African countries. Consequently, aid levels to African countries vary based on provincial interest. For example, many projects are undertaken in Uganda and Tanzania, covered by Yunnan and Shandong province, respectively. Meanwhile, no province is responsible for Egypt and few or no projects are carried out there.

One disease the Chinese are particularly trying to curtail is malaria. Although preventable and curable, 92 percent of global malaria deaths occur in Africa. A decade ago, Chinese established dozens of anti-malaria centers, a national strength. In fact, China’s first female Nobel Prize winner, Tu Youyou, used Traditional Chinese Medicine to discover a malaria treatment. Over the years, China has donated more than 200 million renminbi ($26 million) worth of anti-malaria drugs to 35 African countries.

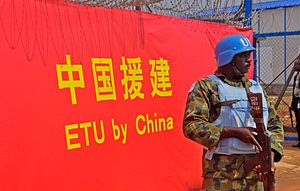

China has also responded to specific medical emergencies on the continent. Between 2013 and 2016, more than 11,000 people died when highly contagious Ebola struck. In response, China dispatched more than 1,000 medical professionals to West Africa, providing 750 million RMB ($120 million) in aid.

When providing aid, Chinese doctors inherently gravitate toward familiar, domestic companies. Chinese suppliers often specialize in distributing low-margin, generic medicines, which can be profitable on a continent with 1.25 billion persons.

Last year, it was announced that, for the first time ever, Ethiopia is constructing a privately-funded Chinese hospital. As part of the Silk Road initiative, Seychelles Afei Holding Co., Ltd. is backing the $30 million, 600 bed hospital. And Liaoning-based Neusoft Medical Systems Company Ltd signed a deal with the Tanzanian government to build a medical equipment manufacturing facility, the largest in Africa.

“China’s pharmaceutical companies and equipment enterprises are developing rapidly,” said Longjiang Shen, associate chief physician at Fourth Hospital of Changsha, who spent two years at Zimbabwe’s Harare Central Hospital.

Dr. Lauren Johnston, an economist at the University of Melbourne who did her Ph.D. at Peking University and worked for Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Planning and Development, said humanitarian support, not economics, drives China’s medical aid. She added, however, that higher health standards are conducive to economic development. And with China wanting to do business with African countries, “solving the public health issue is just an obvious win-win,” she said.

There are challenges when providing aid. Shen said he experienced disruptive employee strikes and a shortage of medical drugs, supplies, and equipment. Better-off patients can afford pain relievers and anti-bacterial bandages. The destitute accept pain and use saltwater as a disinfectant. “Many poor people cannot afford simple surgeries,” he said.

Remedies are not always cutting edge. Advanced medical systems, for example, often cure prostate cancer with drug treatments or minimally-invasive surgery. In Zimbabwe, Shen said, surgical castration is commonly performed.

Brain drain is also a problem. A 2011 study titled “The financial cost of doctors emigrating from sub-Saharan Africa,” found that sub-Saharan countries lost $2 billion by training doctors who immigrated to developed nations.

Skilled doctors who remain often go into private practice. Thus, public hospitals have a handful of high-level management executives, complimented by many entry-level nurses. There aren’t, however, many able, middle management professionals. There is limited resident training and, Shen said, “Because the network is undeveloped, knowledge spread occurs slowly.”

Additionally, Shen said, “The local government is corrupt.” He worries that grants will be funneled into public practices. In the Corruptions Perceptions Index 2016, Transparency International ranks Zimbabwe 154th out of 176 countries.

Foreigners encounter additional challenges, including unfamiliar ailments. Fournier gangrene is rare in China, but common in Zimbabwe. The spread of Ebola and other infectious diseases is also concerning.

Some 1,500-2,000 languages are spoken across Africa. Shen had limited English-language training and had particular difficult speaking with elderly patients, many of whom don’t speak English. To interpret, he relied on younger generations and his mobile phone.

He said cultural differences were also significant. Contrasting with the Chinese, many Zimbabweans viewed afflictions and outcomes as God’s will. Doctors were simply intermediaries providing assistance. Owing to traffic and security concerns, Shen rarely ventured far from Harare. The married father of one also missed his family and hometown.

But there were rewards as well. “[Patients] are very friendly to Chinese physicians. The doctor-patient relationship is much better than in China.” He recalled a touching experience of an impoverished family that came to him in tears, seeking treatment they couldn’t afford for their young son, which Shen provided.

Cynics have raised concerns, viewing Chinese aid as politically or financially motivated. Unlike U.S. aid, which stresses democratic governance and transparency, China explicitly takes a noninterference approach. At the 2015 China-Africa Summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “Africa belongs to the African people and African affairs should be handled by the African people.”

Additionally, Chinese parties on the ground in Africa can have detrimental impacts by scamming locals or building shoddy hospitals. In Uganda, for example, weak regulatory oversight has led to reports of quack Chinese doctors operating private clinics.

And in more than a dozen African nations, a Chinese multilevel marketing scheme sells devices and supplements that are advertised as cure-alls for conditions including hernias, diabetes, kidney deficiencies, and cancer. Given China’s long history with herbal medicine and that the products travel 6,000 miles from China, prospective buyers place additional faith in them.

Although there are risks and unscrupulous actors cause harm, Shen sees the overall mission as philanthropic. “As a large, powerful country, China has responsibility to assist lagging countries,” he said. “We need to improve their expertise level and improve lives for patients.”

Dr. Long Wang is Associate Professor in the Department of Urology at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. Joshua Bateman is based in Greater China and can be reached @joshdbateman.