Australia now sits as a member of the UN Human Rights Council for the first time, sharing an enhanced responsibility to promote and protect human rights globally. This commitment must be robustly pursued in neighboring Southeast Asia, where human rights are under assault and states are reluctant to call each other out on international law violations.

The ASEAN-Australia Special Summit this past weekend brought regional leaders to Sydney, including Myanmar’s de facto civilian leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Alongside talks on business and counterterrorism, the Australian government is duty bound to vigorously raise human rights concerns. Australia should also re-evaluate defense cooperation in the region, particularly in Myanmar.

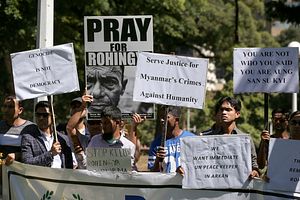

The scale and intensity of rights violations against Rohingya civilians, perpetrated by Myanmar’s military, rates among the worst ASEAN has seen in recent memory. The Rohingya plight has been of regional concern for some time, largely due to effects of refugee movements. The commission of acts constituting crimes under international law has escalated the situation to a global level.

On March 12, UN experts tasked with fact finding presented more horrific reports to the Human Rights Council. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights says acts of genocide may have occurred and that ethnic cleansing continues. Crimes against humanity of murder, forcible transfer, persecution, and rape are among those attributed to the military in Rakhine state and in the conflict-affected north.

Both the civilian and military branches of Myanmar’s government staunchly contest claims of widespread or systematic rights violations. They argue the military campaign is an appropriate response to attacks on police by Rohingya militants, who are voraciously labeled as terrorists. Humanitarian agencies, independent media, and UN investigators are denied access to areas of concern.

Disregarding the state’s obligation to duly investigate and prosecute crimes, Myanmar diplomats have asked for “concrete evidence” of violations. It’s an absurd request given the ongoing prosecution of two Reuters journalists for investigative work, and the substantial body of evidence collected by the UN and nongovernment organizations, despite restricted access.

Australia continues modest but symbolically significant defense cooperation with the Myanmar military, a stance at odds with European and North American allies, who have mostly cut these ties. Persistent military involvement in international crimes demands a re-evaluation of this support. The “quiet diplomacy” approach, by its nature hard to measure for efficacy, appears to have failed, as the ferocity of security operations is unchanged by recent years of renewed defense cooperation.

Given the scale and intensity of violations in Myanmar, Australian engagement that does not at its core address human rights violations will inevitably be self-defeating. At minimum, future assistance must address the policies and practices that encourage or enable rights violations at the operational and tactical levels. Myanmar’s invocation of its Counter Terrorism Law as cover for indiscriminate and unlawful killings gives further reason for caution (a counterterrorism conference accompanied the summit in Sydney).

Broad democratic gains and wider reforms are seriously threatened by military impunity and a lack of government accountability. Defense cooperation is now patently indefensible without addressing accountability and redress in line with international law.

Placing human rights at the center of engagement would better position the Australian government to implore neighbors to address the crisis caused by Myanmar’s military. An application of regional pressure would serve as a critical motivator for the Myanmar government to recognize the crimes and to address cyclical patterns of violations.

Myanmar’s state media regularly trumpets signs of regional support for its obstinacy. Take for instance the theatrical example of Senior General Min Aung Hlaing’s recent trip to Thailand, where he received the award, “Knight Grand Cross of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant.” Recently the military chief, unanswerable to the elected government under constitutional arrangements, was welcomed by ASEAN defense chiefs at another meeting in Singapore. But outside these overt public displays, there is discontent in ASEAN with Myanmar’s handling of the crisis and with the unwanted instability this brings.

While ASEAN is generally viewed as reticent on human rights, linked to a principle of “noninterference” in the affairs of its member states, divergence from this has occurred when rights concerns take an international dimension. This has particularly been the case for Myanmar: in 2006 the government abdicated its inaugural ASEAN chair in response to regional pressure on rights, and more recently Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak publicly contemplated intervention to protect Rohingyas (a significant move regardless of potential domestic motives). Yet regrettably the bloc has been mostly silent on the current crisis.

This lack of regional pressure, an existence of discontent, and the precedents for rights talk within ASEAN, open space for and demand Australian leadership. As a strategic partner of ASEAN but outside the bloc itself, and as a member of the Human Rights Council, Australia is both well positioned and duty bound to robustly engage on the human rights situation in Myanmar, with a view to convince ASEAN members and the responsible authorities to reign in the military and fulfill obligations under international human rights law.

The Australian government must speak forthrightly on human rights, and match this by reviewing defense assistance to states that flout international law. Failure to publicly address and push accountability for crimes of the scale seen in Myanmar would embolden perpetrators of human rights violations throughout the region.

Sean Bain is the Yangon-based legal adviser with the International Commission of Jurists.