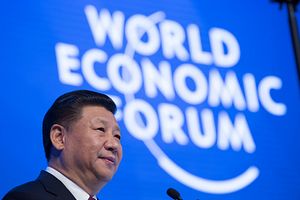

Speaking at the 19th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping outlined his overarching foreign policy objective of moving China “closer to center stage” of world affairs. A few months later in March 2018, addressing the National People’s Congress delegates, Xi further spelled out his vision for the world.

“The Chinese people have always paid close attention and provided unselfish assistance to people who still live in war, turmoil, hunger, and poverty… China advocates that all issues in the world should be settled through consultation,” Xi said. In order to facilitate these efforts, he added, “China will contribute more Chinese wisdom, Chinese solutions, and Chinese strength to the world.”

Since the 1980s, China’s engagement with the wider world has largely been in the context of its core national interests: maintaining the primacy of the CCP in domestic affairs, safeguarding territorial integrity and sovereignty, and ensuring economic development. Under Xi, there has been a shift with Beijing’s global actions now increasingly defined by — although not limited to — the Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to build infrastructure and trading connections linking Asia, Europe, and Africa.

This has meant a greater emphasis on China’s role as a defender of the global commons, as evident by its contribution to UN peacekeeping operations, expanded role in combating piracy in the Gulf of Aden and commitment to preserving multilateralism, globalization, and the international nonproliferation regime. These actions, the argument goes, underscore China’s emergence as a credible voice for peace on the world stage.

However, with developing countries, many of which are suffering from political instability, ethnic unrest, and even armed conflict, comprising a large majority of BRI partner nations, that contention is likely to face greater scrutiny. As Chinese engagement with and interests in these countries deepen, it is invariably leading to a gradual jettisoning of the doctrine of noninterference in favor of greater involvement to ensure stability for and security of Chinese investments, projects, and personnel.

The question, therefore, emerges: how is China looking to address political and ethnic strife across a diverse set of states in order to secure its interests? Answering this requires an examination of the Chinese model of governance, which Xi in effect is proposing as an alternative to the Western-led liberal economic and democratic model.

At its core, the Chinese model prioritizes political stability via control measures coupled with largely state-driven economic, developmental, and poverty alleviation efforts. That has been the grand bargain or underlying social contract that the CPC has offered Chinese citizens.

It is a model that has yielded reasonable social stability while providing strong economic returns for a large majority of Chinese citizens, as evident by the country’s infrastructure expansion, near elimination of absolute poverty, and emergence of a booming middle class. This success has been contingent on a number of factors, such as the sociopolitical dominance of the CCP and its control over the armed forces, expanding state capacity, the ethnic and social make-up of the population, and China’s history and culture. However, the byproduct of this model has been concerns over corruption, regional developmental disparities, deepening inequality, industrial overcapacity, and increasing environmental pollution. In addition, the control measures have meant greater domestic security expenditure, clamping down on religious, social and political freedoms, and deepening ethnic discord.

This is the approach that Beijing is now seeking to offer at the international level. Unfortunately, it is deeply flawed, from its philosophical foundations to its disregard for ground realities. For instance, discussing the issue of peace in the Middle East in June 2017, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi explained that turmoil in the region “is rooted in development, and the way out ultimately lies in development.” Similarly, while proposing a three-phase solution to the Rohingya crisis between Myanmar and Bangladesh in November 2017, Wang was categorical in saying that “China believes that poverty is the root cause of turbulence and conflicts.”

Development and economic growth, in as much as they expand opportunities, improve services, raise standards of living, and ensure efficient allocation of resources, are indeed key components of the conflict-resolution matrix. However, viewing social and political conflicts merely from a economic prism is strategic myopia. Such a perspective glosses over historical divides, deep-seated ethnic, religious and even linguistic fissures, along with stakeholder grievances over lack of participation in governance. These are crucial components of peacemaking, particularly in the context of multiethnic and multireligious postcolonial states.

Moreover, it appears that Beijing is disregarding capacity limitations with regard to other states along with the political costs that some of these governments or leaders are likely to incur in imposing control measures that are even remotely akin to those imposed by the Chinese state. Failure to incorporate the above in its peacemaking strategies will rapidly erode Beijing’s political capital as a potential broker and undermine the Chinese model’s viability as a competitor to the liberal democracy model.

It also provides greater credence to those who view Beijing’s rhetoric of peace as insincere and contend that its actions are driven merely by its limited interests, pointing to China’s role as a peace broker in Myanmar’s long-running civil war. China’s recently reported talks with Baloch separatists in Pakistan are also likely to be viewed in the same vein. Such a perspective gaining steam will bring fresh risks for Beijing.

The fact that Xi chose to represent an ethnic minority region at the NPC this time around indicates a tacit, yet limited, acknowledgement of the above. Perhaps such thinking will in time percolate into its diplomacy, given that the Chinese model for export is largely an extension of domestic strategies. Until then, it is unlikely that Beijing will be able to resolve the fundamental dilemma stymieing its global peacemaking ambitions: can a state that practices stringent repression and restriction on sociopolitical participation within its borders credibly advocate the sharing of economic and political power in other societies?

Manoj Kewalramani is a research analyst studying Chinese foreign policy with the Bangalore-based Takshashila Institution. He also curates a weekly brief, Eye on China, which tracks developments in China from an Indian perspective.