On Wednesday, it was reported by Handelsblatt that 27 out of 28 EU ambassadors to China signed a report criticizing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Hungarian ambassador was the only exception. It is unclear when the report will get published, and whether Handelsblatt saw a draft of the report or a finished version. However, if Handelsblatt’s claims turn out to be true, it will mark one of the biggest setbacks the BRI has seen to date.

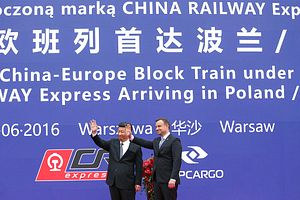

Europe is the final frontier of the land routes central to the BRI. Every day trains from the Chinese trading hubs of Yiwu, Chongqing, and elsewhere begin epic three-week journeys to Europe – ultimately arriving at distribution hubs in Duisburg, Madrid, and London. Moreover, the 16+1 Initiative between China and 16 Central and Eastern European countries is heavily linked to the BRI. Yet the success of further opening up of trade routes into Europe, Chinese infrastructure projects in the region, and the entirety of the 16+1 Initiative are threatened by Europe’s increasing reticence with Chinese involvement in the region. This latest report focusing on the BRI is merely the tip of the iceberg.

The report’s primary critique of the BRI is that it “runs counter to the EU agenda for liberalizing trade and pushes the balance of power in favor of subsidized Chinese companies.” This critique is not new; there has been concern for some time that the projects that make up the BRI, particularly in the infrastructure space, are often being discussed on a bilateral basis, while flouting international trade and investment rules. Indeed, China might be using its financial muscle to force smaller recipient countries to negotiate in this way.

Whilst this narrative undoubtedly hides a deeper insecurity that Western multinationals now fear Chinese competitors more than ever before, there still remains considerable truth to it. The Belgrade-Budapest Railway is a case in point; in the early discussions of the project, Chinese financiers and their Hungarian partners wanted to keep bidding closed and nontransparent, in doing so circumventing EU regulations. The project was ultimately stalled by EU authorities until a more transparent bidding process was adopted.

This approach is reflected in the fact that 89 percent of projects that are labeled as part of the BRI have been implemented by Chinese companies. Foreign companies complain about their lack of access to the BRI, and combined with China’s reluctance to welcome foreign investments, it casts doubt on whether the BRI is a two-way street. Even though Chinese rhetoric around the BRI has international aspirations and calls for enhanced international participation, it remains effectively a Chinese initiative. To become truly international, the BRI needs to be more than just a vehicle for Chinese investments overseas. It needs to promote idea sharing and evolve by adopting international best practices through an inclusive consultative process with partners, both Chinese and non-Chinese.

The positive for China is that the EU ambassador’s report is not an outright rejection of the BRI. Indeed, it still leaves open the prospect of European collaboration on the BRI – but if and only if Europe’s concerns are addressed. As one senior EU diplomat stated, “We shouldn’t refuse to cooperate but we should politely yet firmly state our terms.”

Chinese policymakers are doing their utmost to brand the BRI as epitomized by “win-win cooperation.” Clearly, this report shows that there is a marked disconnect between that rhetoric and the perception of policymakers in the world’s largest trading bloc. It should serve as a warning to Chinese policymakers as to what the consequences might be if the BRI continues to lack inclusiveness, fails to invite foreign participants, and does not act as a two-way street.

It’s not inconceivable that, following in the footsteps of Europe, other economic blocs could begin to band together to voice their concerns surrounding the BRI. For the sake of the BRI’s success, it would be better for Chinese policymakers to pre-emptively address those concerns, as opposed to continuing to create the impression that the initiative remains a panacea.

Ravi Prasad is a Yenching Scholar at Peking University and Co-Founder of www.beltandroad.blog