With its One Belt, One Road Initiative and other policies, China has unveiled its own vision for regional order in an effort to expand its political and economic influence. Meanwhile, the United States has decided to impose sweeping tariffs on major Asian trading partners, including China. This decision by the Trump administration has prompted significant resistance and concern from the affected countries, and has made the outlook for East Asia even murkier. With all this happening, Japan finds itself in an extremely difficult position as it strives to maintain a regional order that is favorable to its own interests.

That is not to say that Japan is standing idly by. In addition to the bilateral approach Japan has traditionally assumed in its Asia policies since the end of the Cold War, it has gradually placed a greater weight on multilateral initiatives. Given the even greater difficulties of today’s climate, Japan is arguably placing even more importance on multilateral diplomacy and pursuing a multi-layered, multilateral regional strategy.

In specific policy terms, the most obvious measure is promoting integration of the Asia-Pacific region based on TPP-11. It is widely known that from January 2017 onwards, after the Trump administration withdrew from the TPP, Japan took the initiative in forging a deal on TPP-11. This was not an attempt to achieve integration at the exclusion of the U.S.; rather, the aim was to bring the United States under the Trump administration back into the fold of Asia-Pacific regional integration. The ultimate goal of the TPP is also to preserve and reinforce a liberal international economic order that basically approves of globalization. From a long-term perspective, however, TPP-11 is simply a transitional framework. The fact that the United States is not part of the TPP is a major issue, but neither is China, the world’s second largest economy and one with a network of interdependencies throughout the regional economy. On top of that, the ASEAN economic community has already been established, and only four of the ASEAN nations working towards regional integration are TPP members.

The second issue is the promotion of regional economic integration in East Asia through RCEP. This framework approaches the economic integration of East Asia primarily through ASEAN nations, and with both China and India as members, while not perfect, it could forge a reciprocal relationship with the TPP. RCEP is the embodiment of the CEPEA (Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia) concept advocated by Japan, and is also an important framework that emphasizes ASEAN centricity, something Japan itself has long done. While RCEP negotiations are slated to conclude this year, they are yet to reach a critical juncture that will determine how the views of China, India and certain other ASEAN nations that do not always fully support the norms and rules of liberal international economic order are incorporated, and whether rules to further advance regional integration can be developed.

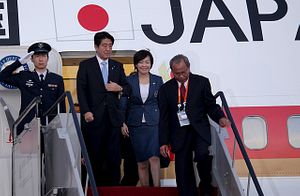

The “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” strategy Japan has pushed in recent years is another topic of debate. In an address delivered by then Minister for Foreign Affairs Fumio Kishida in India in 2015, a speech given by Shinzo Abe at TICADVI in August 2016 and a joint statement issued during Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s visit to Japan at the beginning of this year, Japan outlined its concept for achieving peace and prosperity by strengthening connectivity between the Indian and Pacific oceans, and between Asia and Africa. The Japanese government has currently positioned economic cooperation with a particular focus on infrastructure development along with strengthened connectivity as the centerpieces of this strategy. Maintaining a stable, rule-based maritime order in the Indo-Pacific and the preservation of international order grounded in values such as democracy and human rights are also key elements. In November last year, the diplomats of Japan, the United States, Australia and India met for a quadrilateral dialogue. Based on discussions concerning the Indo-Pacific region, we can surmise that stability of the region and stronger cooperation between major countries to maintain a desirable liberal international order have been incorporated as part of this concept.

It is too soon to say whether the Indo-Pacific strategy will be seen only as an effort led by Japan to tighten the noose around China. The Indo-Pacific strategy includes many elements, because for Japan, it is a concept to achieve broad-ranging, long-term goals such as finding a regional order that works not only for Japan but for other countries in the region as well. Still, one cannot deny that the Indo-Pacific strategy has elements that does permit the interpretation that Japan seeks to exert a measure of control over the rise of China, both economically and politically. Similarly, the concept emphasizes a strengthening of the liberal international order with an emphasis on values such as democracy and human resources, something that is clearly at odds with the direction of the policies China is currently pursuing. Moreover, from the perspective of ASEAN nations that emphasize ASEAN centrality, the fact that the positioning of ASEAN within this strategy was vague, at least initially, was a major cause for concern. Given all this, the challenge for Japan is to advance the Indo-Pacific strategy as something with inclusive qualities that also incorporate China. In that sense, the mention that Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made during his policy speech to the Diet at the start of this year of the possibility of cooperating with China in infrastructure development is a positive development.

The specific policies that make up the multi-layered, multilateral regional strategy being pursued by Japan each come with their share of possibilities and problems. How Japan deploys these policies moving forward will likely have a significant impact on the role of the future regional order in Asia.

Mie Oba is a Professor at the Tokyo University of Science.