Afghanistan’s relationship with Pakistan has been marred by border disputes, proxy wars, and political disagreements ever since the country’s creation in 1947. But especially in recent years, the relationship has been on a downward spiral. Pakistan is accused of providing cover for the Taliban, which are relentlessly attacking Afghan and international targets. Similarly, Pakistan accuses Afghanistan of harboring anti-Pakistan insurgents and this has led the country to threaten Afghanistan with the expulsion of its sizable Afghan refugee population. Meanwhile, Afghans continue to call for international sanctions against Pakistan.

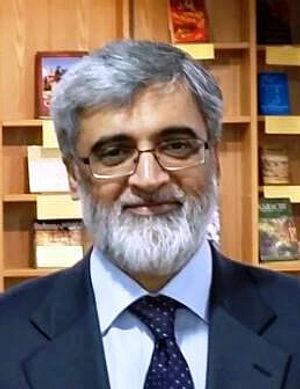

As violence grows, diplomatic efforts are underway to reconcile the two neighbors. Maija Liuhto spoke to Pakistan’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Zahid Nasrullah Khan, in Kabul, about recent trends in the Afghanistan-Pakistan relationship.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

When Ashraf Ghani first became president, relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan seemed to be on the mend, but then they quickly took a downturn. Last month, your prime minister visited Kabul – how would you assess the situation right now?

Right now there is a great willingness from the Afghan government to engage with Pakistan and to persevere against the ground realities which are bound to occur in a conflict situation. An indication of that is that during the prime minister’s visit we agreed on seven principles for the finalization of Afghanistan-Pakistan Action Plan for Peace and Solidarity (APAPPS). Under this plan we have five working groups, which will allow us to have a structured discussion on our bilateral relations. And these working groups are political and diplomatic, [focusing on] refugees, border management, the economy, military-to-military, intelligence-to-intelligence. The sixth working group is a review group, both under the deputy foreign minister level here and our foreign secretary. If there are any road blocks in these working groups, this review group will try to resolve them and find solutions.

So you are saying the relationship is improving – despite the fact that we have seen some border clashes between Pakistani and Afghan forces quite recently?

Yes, this is a good question — that is why I am mentioning there is a will now in the Afghan government. I’m saying “the Afghan government” because that will was always there on our side. Therefore they agreed on those seven principles, [one of which was] that there will be no blame game. And we also agreed that both countries would not allow any third country or group or network to use its soil against each other. And another important point was that both countries would also take action against the irreconcilables. So despite these border clashes, which may also happen in the future as long as the border remains undemarcated despite the best intentions of both sides, the two sides now have the determination to continue working toward the larger goal of peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan, Pakistan is blamed for harboring cross-border terrorists and Pakistan also blames Afghanistan for doing the same. What do you think needs to be done to resolve this issue?

This is an issue which is a major cause of distrust between the two countries and that is why we are having this structured discussion under APAPPS to devise the mechanisms, to end cross-accusations and recriminations, and have a mechanism in place where these allegations could be checked. [In practice, this would mean] the appointment of liaison officers who would have joint supervision, the coordination and checking of [tips]. For example, if they give us an information that there’s a certain madrassa in Pakistan which is preaching radicalism and extremism and, a common allegation, that [the students] are getting prepared to be sent to Afghanistan, so we will take action and we will have their liaison officer on board with us so he can see that on that particular [issue] coordinated action has been taken.

Another common accusation against Pakistan is that your country is not only providing safe havens to these terrorist groups but is in fact actively involved in supporting the insurgency. How do you respond to these allegations?

As you know, the United States entered Afghanistan in 2001 and then the Iraq war started in 2003. The U.S. strategy changed then and the internal conditions in Afghanistan were ripe for insurgency to take over, which it did. They had to find someone to accuse and, of course, the best thing was to accuse Pakistan.

Since the Afghan war, since 1979, we have taken in all types of people from Afghanistan in huge numbers. The entire Afghan leadership that is right now here in the National Unity Government (NUG) has at some time been living in Pakistan, [as has] the entire mujahideen leadership. We do not deny that there could be remnants of Afghan leadership in Pakistan but we ourselves are victims of terrorism and after the Peshawar [Army Public School] attack in 2014, we have wiped out all sort of organized terrorist support infrastructure. However, there are remnants over there; we accept that, but there is no organized presence, there is no support from Pakistan at all. We have made that very clear to the Afghan government in our interaction at the highest level – both our prime minister, and the chief of army staff was also here in October – that we have no love lost for the Taliban or for the Haqqanis at all. And that is why we are fencing the border. And we have deployed more than 200,000 troops on the Afghan border because it’s a very long border and we keep getting these accusations that [the terrorists] are coming across. We have more than 750 posts on the border as compared with 200 posts on the Afghan side. So we are not allowing either people to come from Afghanistan or from Pakistan. We are trying our best.

However, Pakistan will continue to be put under pressure because that is good politics. It sells in Afghanistan and it sells internationally as well.

There is quite a bit of opposition to this idea of a fence in Afghanistan, mainly among the Pashtuns. What has the government’s response been?

[The government is] not opposed to fencing as such. The only issue I would say is that there are claims and counter-claims as to where from this fence may run because the border still is undemarcated. So that is where the issue arises. However, Pakistan and Afghanistan at the level of director general, military operations have agreed to establish ground coordination centers at Torkham and Chaman. This will be manned by a colonel and a major from both sides and here they can then discuss on daily basis these border issues, including fencing.

I think the problem and the elephant in the room in Pakistani and Afghan relations is the formal recognition of the border. The Afghans have to come to terms with it and they have to recognize that what they call the Durand line is now a formal border between the two countries. It is internationally recognized as such and this problem will come to an end. However, both countries do need to work very closely together for the exact demarcation of that line on ground. So sometimes when we are fencing, they have their claims that “this is not your side, this is our side.”

But let me tell you that we have until now fenced only 100 kilometers out of 2,611 kilometers of border. And those are the areas from which the militants come in, the key districts [in the] provinces of Nuristan, Nangarhar, and now going down to Kunar. Because that’s the most difficult geographical terrain from which there are mountain passes and from which they have traditionally tried to come in. Our posts actually come under heavy attack from these places, from these militants, which are in ungoverned spaces in Afghanistan.

Pakistan has threatened to deport the entire Afghan refugee population residing in the country despite the fact that the security situation has been deteriorating in Afghanistan. But the deadline for the expulsion has been extended several times now, most recently until the end of June. What were the reasons behind this?

We are facing specific security and economic challenges due to the presence of refugees we are hosting for the last 40 years, so there is a concern that refugees must return. It’s very important to cut this umbilical cord which got created in 1979 between Afghanistan and Pakistan. We have 1.27 million refugees and around 1.5 million undocumented Afghans, out of which we have documented around 300,000 and we have issued them Afghan citizen cards on the arrangement that eventually Afghanistan would give them Afghan passports and they would return to their country. So that large mass of the population of Afghanistan has to return; however their return has to be voluntary, gradual, and dignified. Pakistan and Afghanistan will work out a practical plan which would ensure the safety and well-being of the refugees in Afghanistan and would take into consideration the capacity of the Afghan government to honorably resettle the refugees. Currently they have nothing to come [home] to in Afghanistan. This was the reason behind the deadline extensions.

In February, Ghani made a comprehensive peace offer to the Taliban, but so far we haven’t seen a clear response from the group. In the past Pakistan has been expected to use its influence over the Taliban to bring them to the negotiation table. How much influence does Pakistan have at the moment?

We have communicated this to the international community, including the U.S., that one thing needs to be understood: the Afghan character is very independent. Even when the Soviets withdrew in 1989, and we had a lot of influence with the mujahideen because we stood with them in that proxy war, they never listened to us and they were never able to reach any agreement. Then, the second instance was when Mullah Omar was in power and 9/11 happened. Pakistan was the [only] country that was recognizing that government, even the UAE and Saudi Arabia had stepped back, but he never listened to us.

So yes, we have influence, but limited influence. You cannot expect Pakistan to guarantee that they will listen to us – they may not listen to us. And also within the regional environment there are now also other countries with which Taliban have good contacts, their leadership especially.

Are there any signals that the Taliban would actually agree to negotiate directly with the Afghan government instead of the U.S.?

We don’t know – what I will say will be purely speculative. Let’s hope so, because we have also called on the Taliban to accept this peace offer. We fully support President Ghani’s offer, which we think is a genuine offer and has opened the door for the Taliban to come and participate politically as a political force in the country.

Pakistan has a very negative image in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s contribution to the country’s development is always overshadowed by security and political issues. What are your main projects here?

Actually you would also feel that there is a sort of a media blackout against Pakistan. So if I meet a minister or I meet somebody of significance it’s not in the newspapers. It’s not shown at all. Even if you go to the presidential website, you’ll be surprised there’s no mention of our prime minister’s visit. However, he was given a guard of honor and all so we are all right with that. We don’t mind that; we understand it absolutely.

But we have done a number of projects. We have opened a kidney center in Jalalabad, we have built a school and a hostel here in Kabul, and we have built another state-of-the-art hospital, Jinnah Hospital, which will soon be handed over. We have built a complete unit in Kabul University and in Mazar-i-Sharif we have built a university. But besides these, what we have added to the human capital of Afghanistan is tremendous. We have been giving them for the last three years 3,000 scholarships and from 2018, we have dedicated 200 specialized scholarships only for women. We have been giving them training in plant protection, in operating their kidney centers, and all besides that, a large number of Afghan students, around 100,000, are studying in Pakistan.

In Brussels we pledged $500 million to do other projects for socioeconomic development. We have invited the Afghan government to hold a meeting with us so there can be a need assessment and according to that we are willing to do other projects here.

Maija Liuhto is a freelance journalist based in Kabul, Afghanistan.