When the World Health Organization recently named and shamed the world’s most polluted cities, it contained a notable surprise. Pasakha, a industrial town in the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, was ranked second behind Muzaffarpur in India. With around 150 micrograms per cubic meter of fine particle emissions found in the air, it was above the notoriously smoggy climates of Delhi and Cairo.

The incredibly high rank for the southern Bhutanese town cuts against the country’s pristine image as a particularly ardent environmental protector. Indeed Bhutan’s renowned Gross National Happiness (GNH) Index — the country’s preferred economic performance metric, formalized in its constitution — centralizes its four key pillars as good governance, sustainable socioeconomic development, preservation and promotion of culture, and environmental conservation.

Pasakha is Bhutan’s largest, and often described as its only, industrial hub. Ideally situated given its proximity to raw materials and trade routes via the nearby Indian border, it is home to various smoky ferrosilicon and steel factories. And, as a major employer and market for electricity, the industries have become an important source of revenue for the government in a predominantly subsistence agriculture, hydroelectricity, and forestry-based economy.

The town symbolizes the struggle at the heart of Bhutan’s development model. Without India’s grants, migrant labor, and hydroelectricity imports, the government would have few other nonindustrial income sources to support its sustainable development drive, including free and universal healthcare and education, supporting its high-end tourism industry, and cultural and environmental preservation. That makes Pasakha a somewhat necessary evil for Bhutanese Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay, a vocal environmentalist.

To his credit, he did announce in 2016 that Bhutan was the only country to have a negative carbon footprint, which means its forests are able to absorb more carbon dioxide than is emitted. That’s driven by the country’s own legislation to ensure a minimum of 60 percent of the country’s total land area must be forested at any one time. Any traveler to the country would reinforce that with descriptions of vast verdant mountain ranges, crystal clear glacial rivers and lakes, and in some places, nose-bleedingly-fresh air. But, it shouldn’t distract from Bhutan’s more granular growing pains. Indeed, Pasakha isn’t an outlier.

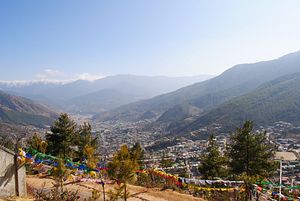

Thimphu, the world’s only capital city without traffic lights (cars are guided by a police officer stationed in a pagoda-like hut) is also struggling with air, noise, and sewage pollution. Rapid urbanization has seen its population swell to over 100,000. While that might seem small, its more than the city’s ancient road and housing infrastructure can cope with. Around half of the 92,000 vehicles registered in Bhutan, as of the end of 2017, are crammed into the capital’s 10 square miles.

With annual growth in gross domestic product (GDP) averaging 7.5 percent between 2006 and 2015, the country is one of the fastest growing in the world. While that should be viewed positively elsewhere, Bhutan’s leadership is likely to be viewing it with caution. Though a boon, the related drop in extreme poverty from 25 percent in 2003 to 2 percent in 2012 has created new demands upon the nation’s sustainable development model.

GNH was coined by the current king’s father, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in 1972 and gathered steam as the nation transitioned from absolute monarchy to parliamentary democracy in 2008. Wangchuck envisioned a Bhutan driven by Buddhist values, but also saw the crucial need for the remote, landlocked country to diversify and modernize to provide welfare, support high quality sustainability, and insure against the risk of natural disasters on agrarian livelihoods.

As such, the nation has had to play a difficult balancing act. Planting trees to maintain carbon negativity is just one of many examples: daily tourist visa rates at about $250 has kept money flowing in, without overrunning the country; hydropower projects, though a renewable energy source, have resulted in some environmental degradation. While the lifting of a ban on television in 1999 was carefully managed with embargoes on MTV, Fashion TV, and wrestling shows, to limit the spread of Western influences, the internet soon followed.

But the Bhutanese leadership can only control so much. With WiFi-ready coffee shops emerging in Thimphu, youngsters in particular are flocking in droves away from rural labor toward the brighter lights of the capital. But the supply of jobs are not satiating them; youth unemployment across the country stands at 13.2 percent in 2016. And that’s placing more pressure on policymakers to diversify the economy, and attract foreign direct investment beyond India. Meanwhile, elders have admonished the gradual dilution of traditional clothing and music, alongside a growing consumer culture.

Therein lies the paradox of the Bhutanese model. Even sustainable growth is a high maintenance endeavor, requiring growth in material wealth to efficiently manage it. But, as Bhutan’s GDP grows, raising “happiness” becomes that every bit harder. The last GNH survey in 2015 found that just under one in two Bhutanese people registered only as “narrowly happy.” Perhaps there is a middle way. For many the country’s growth and exposure to the world has a positive narrative of bringing new ideas, opportunities, and cultural fusions.

Fine-tuning the Bhutanese model will take some time. The nation’s mountainous fortress-like geography may have preserved its society for centuries from external influence, but now the pains of development are acting as an agent of change from within the kingdom.

Tej Parikh is a global policy analyst and journalist. His worked is archived at The Global Prism. He tweets @tejparikh90.