When we speak, write, or even tweet about gender equality and the challenge in achieving it, many men often claim that it is they who are suffering, that their challenges and concerns are being disregarded. Often, these men – particularly in Mongolia – cite the life-expectancy gap as evidence of gender inequality impacting men.

While it is true that the life-expectancy gap is quite large in Mongolia, there is more to this than meets the eye.

When we look at the life-expectancy gap between men and women in least developed countries (LDCs) it is relatively small, but as development sets in, the gap widens. This is due, in large part, to women living longer.

When we look at the life-expectancy gap between men and women in least developed countries (LDCs) it is relatively small, but as development sets in, the gap widens. This is due, in large part, to women living longer.

Women’s access to quality health care is limited in LDCs, and as such, the gap is smaller. So partly, Mongolia’s development over the past decades has subsequently led to the widening of the life- expectancy gap between men and women.

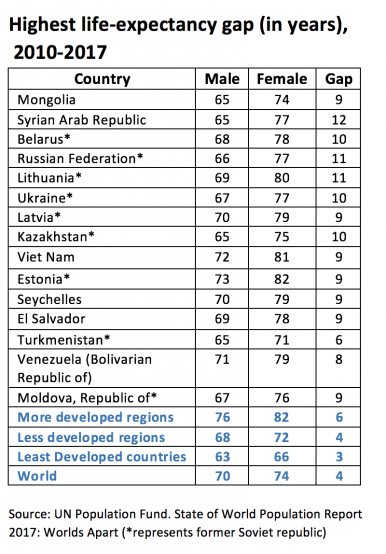

Still, the nine-year life-expectancy gap between men and women in Mongolia is a bit too large as the world average is four years. Such a significant life-expectancy gap seems to be found mostly in formerly socialist countries.

Taking Charge of Your Health

In Mongolia, if we look at the life tables, the death rate for men is higher at all ages, which can indicate not only biological factors but also environmental and behavioral factors are involved.

Take for instance, unhealthy life choices. One study found that 56.1 percent of adult men in Mongolia smoke tobacco, placing Mongolia among the countries with the highest prevalence of male smokers in the world. This contrasts with only 7.8 percent of Mongolian women of corresponding ages smoking tobacco in Mongolia.

Tobacco, as well as alcohol, are considered to be the main risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and strokes – the number one killer in Mongolia – with men dying of these diseases much younger than women.

A study done in the Scandinavian countries has shown that smoking can contribute up to 2.4 years of difference in the life expectancy between men and women.

Similar to former socialist countries, alcoholism remains a serious problem in Mongolia, predominantly among men. The prevalence of binge drinking in Mongolia was 39.7 percent in men and 15.1 percent in women — making it 2.5 times more common in men compared to women.

As well, the number of incidental deaths, including suicide (387 men versus 63 women) and alcohol-related incidences (352 men versus 58 women), were far more frequent among men compared to women in 2016.

Deaths attributed to alcohol, tobacco, traffic accidents, and even suicide are all preventable and point to men living unhealthy lifestyles.

Men need to change their health-seeking behavior as well. For instance, in Mongolia, in 2016, the average number of outpatient visits to health facilities was 4.6 visits for men versus six visits for women (excluding antenatal care visits).

A reduction of unhealthy behaviors would have an almost immediate impact on the life-expectancy of Mongolian men. For sure, we need to do more to encourage men to adopt health-seeking attitudes and behaviors, both in terms of physical and psychosocial health.

Frustratingly, it is not quite that easy.

Overcoming Toxic Masculinities

Many of these behaviors are interwoven into the fabric of Mongolian society as a result of “toxic masculinities” – the adherence to traditional male gender roles that restrict the kinds of emotions and behaviors allowable for boys and men to express themselves.

Toxic masculinities are attitudes and behaviors that are socially constructed — no one is born with these. They stem from stories told in society about how boys and men should behave in order to define their manliness. Anything less is viewed as unacceptable, leading to emasculation.

We see this everywhere we go. We hear our friends tell their boys things like, “Don’t be a girl, because boys don’t cry.” When boys or men get into fights, we say, “boys will be boys” or “men will be men.” We have the expectation that men must provide for their families and be high-earning breadwinners.

Toxic masculinity encourages boys and men to hide their emotions and toughen up: “Don’t be a sissy.” Looking and acting tough is perceived to demonstrate strength, and it defines masculinity. It is considered that muscle equals strength, and feelings (being too emotional) equals weakness. The fear of looking weak has profound impacts on men’s attitudes toward embracing health-seeking behavior and preventing high-risk behaviors detrimental to their health.

Hence, it is no surprise or mystery that compared with women, men are almost everywhere more exposed to alcoholism, drug addiction, serious accidents, and cardiovascular disease. These negatively affect health and as a result men have significantly lower life expectancies.

Gender inequality, and rigid gender roles and the stories that our societies tell us about how men and women ought to behave, are not only toxic for women, but also toxic for men. The roles and stories that are constructed tell us what is acceptable and what is not, thereby confining and restricting all of us in reaching our full potential.

These gender-biased expectations are not helpful for the development of society, and we must all, men and women alike, work to change our attitudes.

Changing and challenging toxic masculinities and encouraging health-seeking behavior through targeted health education programs and campaigns is a positive step to redefining expectations. For instance, UNFPA Mongolia is working with NGOs that can bring awareness to the importance of men being involved in caregiving, and is integrating comprehensive sexuality education into secondary school curriculum to address gender stereotypes at a young age. UNFPA Mongolia has also launched the safe school initiative, which works with teachers and students to eliminate harmful gender norms.

These interventions, as well as others, open up a dialogue to include the importance of our health and well-being, which is important to living a longer and healthier life, applicable particularly to Mongolian men.

Naomi Kitahara, the current UN Population Fund Representative in Mongolia, has spent more than 25 years in the development field.

Ariunzaya Ayush, the current Chairwoman of the National Statistics Office of Mongolia, has more than 10 years of experience in local and national governance.