Earlier this year, Strava, the mobile phone fitness app company, made headlines because their Global Heatmap revealed the movements of its app users from all over the world. This raised immediate concerns, with security analysts warning that the Global Heatmap “unwittingly revealed the locations and habits of military bases and personnel, including those of American forces in Iraq and Syria.”

However, one area of the world that did not receive much attention from the heatmap’s release was North Korea.

Strava’s heatmap of North Korea not only illuminated (literally and figuratively) one of the most opaque areas of the world, but it also provided more insight into the movement of foreign tourists and the possible segments of North Korean society they were exposed to. The data provided by Strava is most likely not from North Korean citizens since their cellular data access “is limited to very specific functions such as reading the state newspaper [and they] cannot access the internet via cellular data.” Additionally, North Korean mobile phones can only have applications that are approved by the North Korean government.

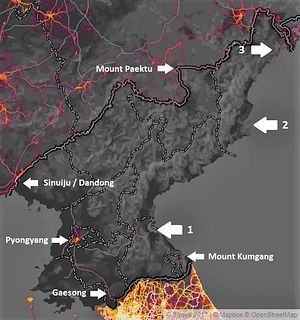

This article provides an analysis of patterns evident in the heatmap for North Korea and a discussion of what they may imply about Pyongyang’s policy toward foreigner interactions with its citizens. Pyongyang, Gaesong, and Mount Kumgang are not included in this analysis because they are well-known foreign tourist destinations.

Not Isolated to Pyongyang

The common belief about North Korea, among non-North Korean watchers, is that foreign visitors are strictly limited to touring the capital, Pyongyang. This belief is supported by the argument that North Korea does not wish outsiders to see the desolate conditions of the approximately 22 million people who reside outside of the nation’s capital. However, as Figure 1 shows, North Korea is willing to selectively expose potentially “wavering” and “hostile” class citizens to foreigners, thereby accepting the risk that such exposure could undermine the government’s posture that it is the “purest” self-sustaining nation on Earth. North Korean society is segregated into three tiers: core (loyal), wavering (50/50 loyalty), and hostile (no loyalty). Most, if not all, of the core class is believed to reside in Pyongyang, while the wavering and hostile classes live in the countryside.

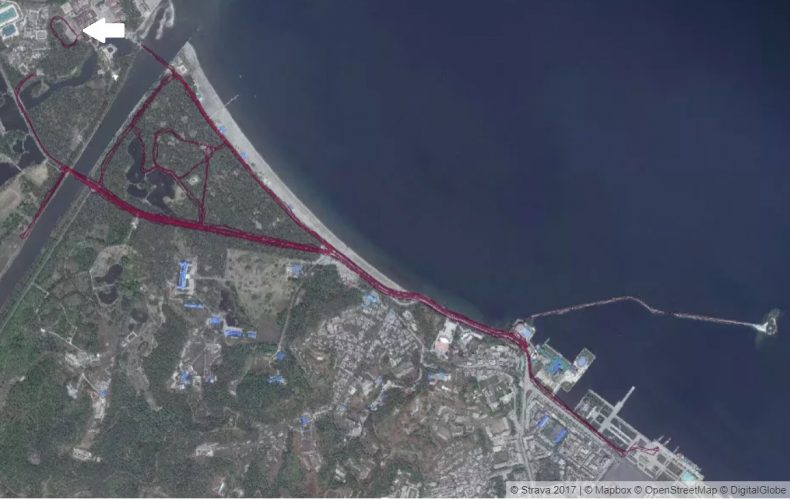

Figure 1 – Strava Heatmap of Wonsan

The first geographic area highlighted is the city of Wonsan. In the close-up image (Figure 1), the white arrow in the upper left points to the location of the Songdowon International Children’s Camp. Opened in the 1960s, the camp’s purpose is to expose foreigners to North Korean culture with the goal of “fostering ties” to other nations. Notably, the camp is a vehicle for North Korean children to interact with their peers from countries like Russia, China, Vietnam, Tanzania, and Ireland. There is little doubt, however, that the children are from the “core” class of North Korean society, which suggests the government is confident that exposing these individuals to foreigners will not affect their loyalty – thus posing no threat to regime stability. Additionally, as noted by Figure 1, the foreigners’ movements appear to be restricted to nearby parks. This may signify that the government is concerned about exposing foreigners to venues that could undermine its positive narrative, such as one of North Korea’s prisons, Kyo-Hwa-So No. 88, which is about three miles to the west of the children’s camp, and one of Kim Jong-un’s “palaces,” which is within eyesight, just a couple hundred feet to the north.

Figure 2 – Strava Heatmap near Mt. Chilbo

The second geographic area highlighted is near Mount Chilbo in the North Hamgyong Province. The close-up image (Figure 2), shows a village where foreigners may come for a “homestay.” Homestays are venues where tourists live with a host family. This is new for North Korea because usually foreigners are confined to designated hotels where their movements are under strict surveillance. Judging from the homestay video by Young Pioneer Tours, a group that provides low budget tours of North Korea, it is unclear if all of the North Koreans at the homestay are part of the “core” class due to their attire, which is dissimilar to the style typically worn by the core class, and tanned skin, which likely indicates they work in the fields. Therefore, these individuals may be part of the “wavering” class but receive the treatment of the “core” class.

This suggests that the government is willing, for political and economic reasons, to expose its wavering class to foreigners, and may indicate that the social class system within North Korea may be more fluid than previously assumed. Nonetheless, repeated North Korean citizen interaction with foreigners could potentially alter their views of North Korea and the outside world. Given that the homestay initiative is only a year old, it is an experiment that could be rescinded. Similar to the situation in Wonsan, foreigners’ movements appear to be restricted, perhaps because the homestay area is close to the nuclear test site at Punggye-ri and the political prison, Kwan-Li-So 16, which is located about 20 miles to the west.

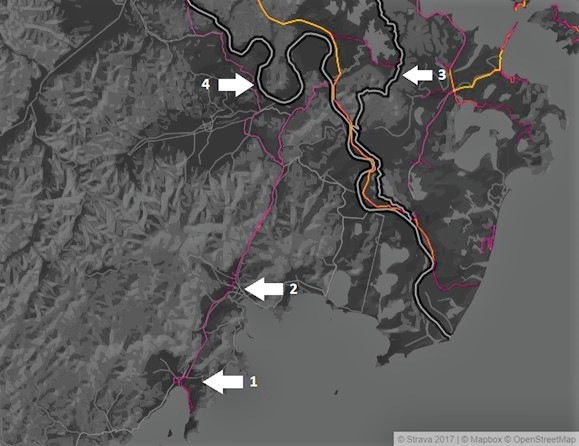

Figure 3 – Strava Heatmap of Rason

The third geographic area highlighted is an area known as “Rason,” which is a combination of the city names Rajin and Sonbong. In the close-up image (Figure 3), the first arrow points to Rajin, the second to Sonbong, the third to the North Korea-Russia border, and the fourth to the North Korea-China border. Rason, a Special Economic Zone (SEZ), was created in 1991 “to promote economic growth through foreign investment.” It is also an important nexus for North Korea, since it is the only city where foreign-owned businesses are allowed, and where North Koreans, Chinese, and Russians can interact on a daily basis. Therefore, it is likely that at least some of the North Koreans there are part of the “core” class.

Judging from photos released by CNN, in 2013, when 40 Western cyclists crossed into North Korea from China, they were greeted by “thousands of people” in Rason who were dressed similar to those from Pyongyang. Interestingly, the route the bikers took from the Tumen River crossing with China to Rason had them pass by many villages. This may suggest that the North Korean government was not concerned about exposing its “wavering” and “hostile” classes to foreigners, likely because they encounter them frequently due to the SEZ. However, given that 18,900 people have defected from this region, the most of any province in North Korea, the overall exposure to foreigners is probably a contributing factor, especially since it is clear that Pyongyang fears interactions with foreigners can affect North Korean citizens’ perceptions of foreigners.

Conclusion

Overall, the Global Heatmap suggests that North Koreans, specifically those residing outside of Pyongyang, have more exposure to foreigners than commonly believed. The willingness of the North Korean government to allow these types of interactions probably reflects several factors: a desire to portray an image of North Korea in softer terms as a modern, humane society; the need to allow some level of engagement, particularly with China, to support its economy; and confidence in its ability to mitigate the effects that these interactions will have on the North Korean population. Whatever the relative weight of these factors in Pyongyang’s calculus, it is clear that North Korea is moving past its status as a “Hermit Kingdom.”

Garrett J.R. Redfield is a researcher for the Institute for Defense Analyses specializing in Korean Peninsula affairs. He is a Korean-American adoptee who has spent extensive time working, living, and studying in Korea. He has a Master of International Affairs degree from the Pennsylvania State University, and is proficient in Korean.

The analysis and opinions presented in this article are the author’s own and are not intended to reflect the view of the Institute for Defense Analyses, the United States Department of Defense or the United States government.