Though Vietnamese politics usually grabs international headlines during the country’s quinquennial Party Congresses, other important intervening political events often go unnoticed. A case in point is this month’s 7th Plenum of the Central Committee, where could be as many as three new faces entering the Politburo, the Vietnamese Communist Party’s top decision-making body.

Early last year, Dinh La Thang, the Ho Chi Minh City party secretary, was dismissed from the Politburo after he was accused of corruption as part of the grand PetroVietnam investigation. It was the first time a Politburo member had been fired in decades. He was subsequently jailed for 18 years. Earlier this year, Dinh The Huynh, a prominent official and head of the Party’s Secretariat, announced he would step down from the body because of ill-health. There are also suggestions that President Tran Dai Quang, who has been suffering from poor health for months, which saw him take an unusual month-long absence from public affairs in August, will be replaced at this month’s Plenum.

Two interesting articles have explored what could take place at the Plenum: one by Le Hong Hiep, of ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, and the other by David Brown, a former U.S. diplomat in Vietnam. As well as promotions to the Politburo, Hiep states that Nguyen Thien Nhan could be named the new State President at the Plenum. Nhan was made the new Ho Chi Minh City party chief following La Thang’s dismissal last year. He had headed the Fatherland Front, an umbrella organization that controls “people’s organizations,” or Party-endorsed civil society.

Nhan might be characterized as an unexceptional Politburo member who appeared to fall out of favor after performing poorly as education minister during the 2000s. One political analyst had told me previously that he expected passive leadership and mediocre performance from him. Indeed, he is widely regarded as a Party yes-man.

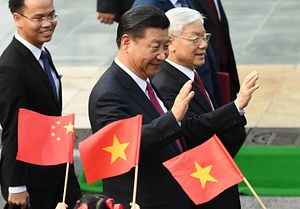

Nonetheless, this may be exactly the kind of person Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, the country’s leading party political figure, would favor. Since the last Party Congress, in early 2016, which saw Trong reelected and then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung relieved of his duties, Trong has ushered in an era of conservative political change. The Party, under his watch, has become more centralized, managed by “consensus” decision making; democratic centralism, if one is being kind.

As Brown notes, Trong wants to “restore party discipline and morality is his campaign to identify and punish ideologically corrupt party leaders.” This was recently codified in the list of 27 “heresies” that will be securitized by a new auditing team, which will report on the morals of Party officials. It also targets politicians considered too individualist and populist, as was Dung and La Thang.

Indeed, the replacement of La Thang for Nhan encapsulates how Trong now wants the Party to operate. La Thang, a politician from the Dung-mold, who was vocally anti-China and spoke from his own pulpit on social issues affecting the poor Vietnamese, was seen as a threat to the Party’s consensus decision-making ethos, once forged by Ho Chi Minh in the 1960s, whereas Nhan, an ardent yes-man with a history in the Party’s duller bodies, is the kind of apparatchik that Trong desires. Indeed, expect this month’s Plenum to see the rise of committed though insipid Party members, most cast in Trong’s image.

Hiep raises another prospect. If Nhan is made the new State President, this could put him in line to become the next Party General Secretary, given that Trong will almost certainly retire at the next Party Congress in 2021. Most analysts, including myself, however, reckon that the most likely candidate to take this role is Tran Quoc Vuong, head of the Central Committee’s Inspectorate Commission. In effect, Vietnam’s anti-corruption czar (though Trong holds equal, if not more, weight in the Party’s anti-graft campaign).

In March, Vuong was also named Executive Secretary of the Party’s Secretariat, a body tasked with implementing Party policy, following the early retirement of Dinh The Huynh, who had been tipped to become the next Party General Secretary. But Hiep notes that if Nhan becomes State President this month, he could mount a challenge for the top job in 2021.

Another political riser worth watching is Nguyen Xuan Thang, currently Secretary of the Central Committee and Director of the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics. Importantly, too, he was promoted to chairman of the Central Committee’s Theoretical Council in March. He had been occupying this position since December, also because of the absence of Huynh. Trong, one must remember, was also head of the Theoretical Council in the early 2000s. With ideology now aggrandized within the Communist Party hierarchy, the Theoretical Council matters – and so might Thang.

Most Vietnamese will no doubt regard the upcoming Plenum with the clichéd, but apt, response: “New boss, same as the old boss.” But what is decided at this gathering will be of importance for ordinary people. For starters, the Central Committee is expected to vote on whether to increase the national retirement age, after Minister of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs Dao Ngoc Dung put the motion before the National Assembly earlier this year.

One option is to increase the retirement age from 60 to 62 for men and from 55 to 60 for women. This would be increased incrementally, by three months each year until the new maximum age is reached. The second option is a more extreme increase; the age of retirement would increase by four months each year until it reaches 65 for men and 60 for women.

The Central Committee is also expected to decide on whether to lower the number of years Vietnamese workers have to pay into the social security fund before they can claim a pension. Currently, they must pay in for 20 years. But Party officials want this to be reduced to 15 years, and possibly to just 10 years in the future.

The reasons for both are clear: While Vietnam currently has a young population, within a decade or two it will have one of the world’s fastest aging populations, increasing the risk that it will grow old before it gets righ (See: “Will Vietnam Grow Old Before it Gets Rich?”). Wealth, here, also includes funds within the social insurance scheme, which economic observers say could begin running into deficits by 2020, and possibly be depleted by 2040.

That is unless things change. Chiefly, this would be done by reducing the numbers of people claiming pensions and increasing the number of workers who pay into the scheme; reducing the numbers of years of contributions, the Party thinks, would tempt more workers and businesses to pay into the scheme.

Given all this, what one might expect from this month’s Plenum, then, is political consolidation by Trong and the further deterioration of the rights of Vietnamese workers, who are already paying the high costs of poor financial management by the ruling Communist Party.