Dark clouds have been hanging over Thailand’s politics for more than a decade now, unleashing a series of crises that have seriously impaired the future of Thai democracy. In 2005, the yellow-shirt People Alliance for Democracy (PAD) launched its months-long protests against Thaksin Shinawatra, then-prime minister of the Thai Rak Thai Party. The PAD accused Thaksin of corruption, and more damagingly, of disrespecting the revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej. At the crux of the problem lay the apprehension among the royal political network concerning the rise of Thaksin, who threatened to replace the old political order with his own. Finally, a coup took place in 2006 overthrowing Thaksin and ultimately driving him out of the country. Thaksin is now living in self-exile in Dubai.

On the surface, it appears that the royal political network had won this political tussle. But the return of the Shinawatras to politics in 2011 showed that the war between the old and the new political classes was far from over. In 2011, Yingluck, Thaksin’s sister, triumphed in a landslide election, becoming the first female prime minister of Thailand. The Shinawatras had impressively succeeded in every election from 2001 to 2011. The repeated successes of Thaksin and Yingluck coincided with the flagging power of the Thai monarchy. Thus, as the royal transition approached, the royal political network sought to eliminate its enemies once more in a coup. Removing Yingluck from power in 2014 was a part of the elites’ effort to manage the royal succession to maintain their political advantages. Evidently, the Shinawatras continued to be perceived as a threat to the royal political network’s privileged position in power.

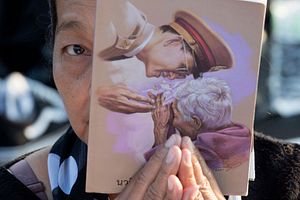

For decades, the royal political network had firmly exercised its domination of Thai politics. The abolition of absolute monarchy in Siam – which would later be renamed Thailand – in 1932, at first weakened the political status of the king. But with the enthronement of Bhumibol in 1946, the glory days of the Thai monarchy were gradually resurrected, made possible through the construction of a new political alliance between the monarchy and the military. Bhumibol worked with military despots to re-establish the political legitimacy of the monarchy. In return, defending the monarchy became a paramount undertaking for the military, as well as a crutch to justify its role in politics.