In 2014, Taiwan saw a massive protest against the economic integration policies of former President Ma Ying-jeou and the ruling Kuomintang (KMT). The KMT had torn down trade barriers with China in 2010 under the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) in an attempt to revive Taiwan’s struggling economy. The results of ECFA proved instead to create a hollowing-out of Taiwan’s small- and medium-sized enterprise manufacturing, hitting the economy even harder, and pushing Taiwan down a path of no return in its dependence on China.

The 2014 negotiation of trade services conducted between the Ma administration and China was the straw that broke the camel’s back. On March 18 of that year, in an act of desperation, protesters occupied the legislature. Their list of grievances was long, and their origins were many. Protesters were not from any single camp. The movement came from an organic dissatisfaction with the ruling party’s policies. When police arrived to barricade the building, a second wave of protesters surrounded the barricades and occupied grounds. Protests grew. Occupiers halted traffic near Taipei Main Station, others managed to storm the Executive offices before being forced out.

The protests were dubbed the “Sunflower Movement.”

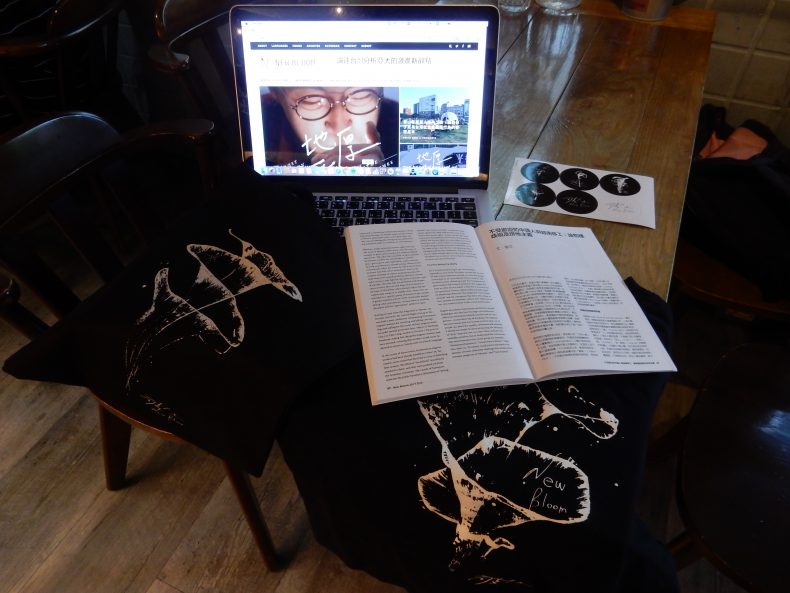

New Bloom, an online magazine, was established in 2014 by participants of the Sunflower Movement as venue to continue the discourse created by Taiwan’s discontented populace. Its focus is on Taiwan’s social issues from a left-independence perspective.

Brian Hioe is one of New Bloom’s founders. He arrived at the protests with the second wave of occupiers in the Legislative Yuan’s parking lot and witnessed the movement’s attempts to occupy the Executive Yuan. The movement grew to its height on March 30, when 500,000 Taiwanese were occupying Taipei’s central government district, supported by untold numbers more donating money, food, and water to the protesters. The occupation lasted until April 10.

New Bloom was established by Hioe and fellow Sunflower protesters with an understanding the dialogue created by the protest needed to continue. Within three months, by July of 2014, the site was up and running.

New Bloom recently celebrated its fourth anniversary. I attended and proposed an interview with Hioe. Below is our discussion on New Bloom, the spirit of the Sunflower Movement, and the Taiwan narrative four years later.

How does New Bloom fit into this post-Sunflower Movement narrative?

Some see us as continuing the attempt to spread the message of the Sunflower Movement to the international world[.] Although, again, we only represent one element of the movement. We have ourselves experienced ups and downs with regards to the broader trends of Taiwanese social movements. [For example,] many members became inactive after 2016 elections. In part, this was probably out of exhaustion, but this was also probably in part because keeping up the work of the publication seemed less urgent after a KMT defeat.

However, personally, I see the role of New Bloom as more necessary than ever in the present moment. A sign of how desperate Taiwan is for international acknowledgement is that, after the Trump-Tsai [phone call in 2016], there are those in Taiwan who have convinced themselves that the Trump administration genuinely has Taiwan’s best interests in minds, rather than hopes to use Taiwan as a potential card to play against China. There are also those [who believe], despite the obvious instability of the Trump administration, long-standing friends of Taiwan within the administration will keep destabilizing forces in check. This is a dangerous belief, one founded on conflating wishful thinking for what is geopolitical reality at present. As such, pushing for a left path to independence, one not solely reliant on the geopolitical might of America, seems paramount.

Similarly, we continue to try and uphold a left political stance which pushes for equality and justice for all, rather than discards this because of prioritizing the independence issue. One notes that the Tsai administration has, for example, adopted a strategy of emphasizing the progressive values of Taiwanese society. Yet confronted with the stark conservatism of the Trump administration, progressive values could actually become a liability for Taiwan. On the other hand, for us, such values are why Taiwan is worth defending.

Four years on, what is New Bloom’s contribution to the “Taiwan narrative?”

I wonder that myself often. I think it is primarily in terms of attempting to carve out a space for “left Taiwanese independence” in English and Chinese discourse.

In English, this has primarily been through engagements with and against those who claim that America genuinely has Taiwan’s best interests in mind in terms of foreign policy, something that has become a particularly heated debate since the Trump-Tsai phone call. I generally point to America’s being perfectly happy to suspend Taiwan in diplomatic limbo for decades in the interests of strategic ambiguity. I also raise the decades in which America backed the KMT to counter China in order to point to how America being anti-China is not necessarily the same as being pro-Taiwan. In Chinese, this has usually been through critiques of the pro-unification Left, those who argue for unification with China on left grounds, although I find that such positions increasingly end up dependent on “blood and soil” Chinese nationalism, and apologism for Chinese expansionism.

Were the elections of 2014 a rejection of the KMT? Were the elections of 2016 an endorsement of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)? Will 2018 be a rejection of the status quo?

The defeats of the KMT in [the] 2014 and 2016 elections generally do point to how the party has lost a great deal of ground and no longer has the hold on the Taiwanese public it once did. However, while the DPP performed well in 2016 elections as a result of the KMT’s weakness, I am not sure that the results of 2016 elections indicate the Taiwanese public supports the DPP uncritically either, as it comes increasingly under fire for deviating from its electoral platform and becoming increasingly conservative.

The KMT may be able to be recoup some of its lost ground in 2018 elections, but I don’t see it managing to turn things around for itself anytime soon, given numerous self-inflicted blunders. The DPP will likely maintain its overall position due to the absence of alternatives. While new third parties did emerge after the Sunflower Movement — termed the “Third Force” — and they differ from the DPP because they are are more politically progressive and lean more openly in favor of independence, they may still lack the resources to compete with the DPP head on and carve out a space for themselves. This still remains to be seen and this is another way in which the ultimate results of the Sunflower Movement are still up in the air.

Did the Sunflower Movement change the national political debate?

I think the Sunflower Movement did change the national political debate, but this is very hard to measure quantitatively, such as by pointing to who was elected and who wasn’t. Instead, this is something that can only be done qualitatively.

Something which is sometimes forgotten is that there was a strong sense of hopelessness among many in Taiwanese society before the Sunflower Movement, as though China could swallow up Taiwan at any time. This has faded, with there being greater confidence in that China could not swallow up Taiwan without resistance.

The Sunflower Movement can also be seen as having reframed the conversation regarding independence/unification. Many also point to the Sunflower Movement as a movement which demonstrated that young people overwhelmingly do not identify as Chinese, as their parents might have, illustrating that they are the “natural independence” generation of those who have no emotional attachment to China, which is to them a foreign land.

Some people say, given Taiwan’s domestic and international problems, another movement is necessary. There’s a lot of romanticization of 2014.

Ironically enough, I think that many Sunflower Movement participants would hope that another movement is not necessary. The movement was an emergency response to what was perceived as a political crisis and it is generally hoped that another crisis necessitating another mass mobilization of society would not be necessary. That being said, at the same time, many of the salient issues at stake during the Sunflower Movement are not yet resolved, particularly regarding independence and unification issues, and so there may be view among some that another movement is needed to permanently resolve these issues.

Do you believe another student movement may spring up?

Personally, I think that this is rather unlikely. High intensity protests from youth activists have taken place since the Tsai administration took office, particularly with regards to changes to the Labor Standards Act. Nevertheless, there has been a marked decline in activist participation since the Tsai administration took office.

This reflects that much of the Sunflower Movement was, in fact, simply a reaction against the KMT and it will take more time for anger against the DPP to concretize into any social movement. Similarly, this illustrates to what extent that the manifestation or disintegration of social movements in Taiwan is dependent on what takes place regarding electoral politics.

I find that unfortunate myself, but that also fits with broader political patterns of behavior in Taiwan.

At the same time, there is a general political pattern of large-scale movements emerging shortly before changes in the presidency take place, as observed with the Sunflower Movement itself, the Redshirt movement that preceded Ma Ying-Jeou taking power, or mobilizations before Chen Shui-bian became president. As such, I am not sure what the stimulus would be, but if it were to happen, a large-scale movement taking place may be more likely to occur at the end of a projected second term by Tsai Ing-wen.

What are New Bloom’s politics?

New Bloom has no set politics, in the sense that we’re not a political organization with a party line or anything like that. However, we’re broadly unified by a “left independence” political perspective, which means that we hope for Taiwanese independence on left, rather than right, political grounds, which means not relying on American power to counteract Chinese power, and call for broader social change on a left political basis. We would see both America and China as infringing on the right of the Taiwanese people to self-determination, for example, which is obvious when it comes to China, but also with regards to America using Taiwan as a chess piece in geopolitical stratagems against China for decades.

How does this left-independence identity compare to say, an average Taiwanese who identifies as a DPP voter?

I think it would be far easier, in fact, for an average DPP voter to associate with a form of “right independence,” which is reliant on America as Taiwan’s security guarantor from Chinese threats. On the other hand, we take the view that America can also prove a threat to the Taiwanese people, and that being opposed to China does not necessarily mean being pro-Taiwan — for example, America was perfectly happy to back the dictatorial rule of Chiang Kai-shek for decades because he opposed China.

Similarly, although the DPP may have “progressive” in its name, the DPP has proven far from progressive with regards to many of its actions since the Tsai administration took office. This includes backing away from pledges during its campaign that it would seek to legalize marriage equality, or passing changes to labor laws that will force Taiwanese workers to work even more hours when the Taiwanese workforce already has the world’s fourth highest working hours and the changes will decrease the ability of Taiwanese workers to collectively bargain with their employers for better conditions.

The DPP sometimes justifies such measures as necessary to safeguard Taiwan’s standing in the world, such as claiming that lengthy work hours are necessary to maintain competitiveness vis-a-vis China. However, we wish to push for another path.

In the context of the Sunflower Movement, how important was independence to the protesters? At its core, was this a domestic movement, or an international movement?

The interesting thing is that, while the key issues of the movement were obviously deeply related to questions of independence and unification, and the movement was readily interpreted as such internationally, such issues did not overtly appear in the movement until very late. The leadership within the Legislative Yuan probably were generally in favor of independence, but they did not express such views openly until the tail end of the movement, for fear of alienating segments of the public through open independence advocacy, or causing the movement to be written off as an incident instigated by independence activists. Such views became clearer after an event was held to commemorate the death of Cheng Nan-jung in the Legislative Yuan on April 7, 2014 and after “Big Bowel Blossom Forums” began to be held to vent steam about the movement.

The movement took place, of course, primarily in Taiwan, although international solidarity activities were organized by Taiwanese around the world. Many new networks were formed internationally after the movement, which could probably allow for quicker mobilizations abroad in the future, if something like the Sunflower Movement should happen again. Both domestic and international issues were at stake — internationally with regards to China, of course, but also with regards to domestic dissatisfaction with the actions of the KMT, rising anger against undemocratic actions against the KMT that seemed to hearken back to the martial law period, and general lack of government transparency. This does not always directly connect back to the external “China factor,” either; it is important to note anger against the KMT was its own motivator for demonstrations even without bringing the KMT’s pro-China policies into the picture — though that, of course, may have been the straw which broke the camel’s back in this case.

Is New Bloom a continuation of the Sunflower Movement, or more of a spiritual successor?

I think it’s truer to say that we emerged out of the movement and we see ourselves in direct connection to the movement’s events, seeing as many of us are people that met during the course of the movement or shortly afterwards. But even then, we’re not representative of the movement, we’re a group of people who were a small part of the movement, although we may be among those who shared certain perspectives during the movement.

Why the name “New Bloom?” Is New Bloom a successor to other, earlier movements?

We picked the name “New Bloom” because many student movements in Taiwan have taken their name from flora. First and most obviously, you have the 1990 Wild Lily movement. As mentioned, we are more directly products of the Sunflower Movement. But preceding the Sunflower Movement was also the 2008 Wild Strawberry Movement, which was about many of the same issues that the Sunflower Movement was.

As such, because we see ourselves as part of this broader tradition of activism in Taiwan and we hope to continue to future waves of activism in Taiwan, we chose the name “New Bloom” — not only to suggest that we were something new that emerged out of the Sunflower Movement, but to allow for future movements to occur afterwards.

Who are New Bloom’s writers?

We’re open to any submissions! Staff-wise, we have anyone from college students to photographers, professors, house husbands, grad students, and freelancers, and our writer pool also varies greatly in terms of what people’s backgrounds are, their ages, etc.

Most often, though, our writers are people who have one foot in academia. I sometimes joke that we are somewhere between “journalism” and something more like an academic “journal.”

***

Today, Hioe has undertaken an ambitious oral history and archival project of the Sunflower Movement entitled “Daybreak,” hosted on New Bloom. His next project is to expand into the history of the KMT’s White Terror period in Taiwan.

Taiwan’s next round of midterm elections will be held later this year.