The “fluid” nature of the contemporary global order has been discussed for quite some time. However, the new U.S. administration has been adding significant depth and speed to this fluidity, combining a withdrawn, isolationist approach to global governance with – more recently – what many commentators have referred to as an outright disruptive (and potentially destructive) one. As the “traditional” steering power veers toward disengagement, the possibility of a “power vacuum” in global governance becomes more and more likely, and this presents major players such as the EU and China with both opportunities and challenges to step up their role.

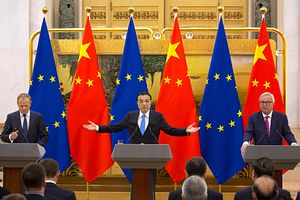

In this light, despite the many still-unresolved bilateral issues, it should not come as a surprise to see Brussels and Beijing edging toward closer cooperation. The recently concluded 20th EU-China Summit appeared to confirm an acceleration of the rapprochement, which was especially evident in its main outcome: the Joint Statement.

The statement, while obviously nonbinding, offers nevertheless important indications with regard to the impact that recent changes in global dynamics have been having on EU-China relations. Especially when compared with its 2015 predecessor, the 2018 statement is noteworthy for its discursive strength. Throughout the document, there is significant emphasis on the need for both sides to “reinforce” their partnership and to make “strong” commitments to improving it.

Among said commitments, it is striking to see how those pertaining to the “global dimension” of the partnership take up approximately 50 percent of the statement, thereby highlighting both sides’ keen awareness of the need to proactively and cooperatively manage what is a highly interdependent international system, including in traditionally very “national” domains such as security and defense. Accordingly, the statement emphasises the importance of promoting multilateralism and a rules-based international order, with an almost overwhelming stress on the need to concretely join forces to combat nontraditional, transnational issues. If we compare this with the dominant U.S. discursive stance (for example, in the 2017 National Security Strategy), the contrast could hardly be starker.

Direct, and in many ways unprecedentedly so, EU and Chinese opposition to the current U.S. approach to global governance emerges in at least three specific areas. First and foremost, the global economy. In addition to stating that the EU and China are “strongly committed to fostering an open world economy, improving trade and investment liberalization and facilitation,” the joint statement adds that both Brussels and Beijing will be “resisting protectionism and unilateralism” in order to make globalization “more open, balanced, inclusive, and beneficial to all.” It would be beyond naïve to not identify the United States as the primary target of this “resistance,” since both the EU and China have been hit with sweeping new tariffs which have ignited a veritable global trade war.

Looking at the joint statement, as well as at declarations made by senior officials on both the EU and the Chinese side prior to the summit, Washington’s protectionist offensive appears to have provided Brussels and Beijing with a common enemy, the fight against which could potentially help speed up the solution to several of the outstanding bilateral hurdles. Indeed, given the urgent need to prevent a complete collapse of the existing international trade framework (both the EU and China have repeatedly pledged their commitment to upholding yet reforming the WTO), it is likely that both sides will see that issues such as China’s management of its overcapacity and broader market access matters could be dealt with more efficiently.

The second area of EU-China agreement – and opposition to the U.S. administration – is climate change. Already in June 2017, in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s decision to pull the United States out of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the EU and China had leaked a joint communiqué vowing to deepen their cooperation, confirming their commitment to the Agreement, and effectively presenting themselves as the only viable diplomatic alternative to deal with such a critical issue. Now, that statement (the “Leaders’ Statement on Climate Change and Clean Energy”) has been officially adopted and annexed to the 2018 joint statement, hence formalizing Brussels’ and Beijing’s firm upholding of the global scientific consensus and hostility to the skepticism that prevails in large swathes of the current U.S. administration.

The third area is nonproliferation. In the joint statement, the EU and China confirm their support for the “continued, full and effective implementation” of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA – also known as the Iran Nuclear Deal), and praise the “continued adherence by Iran to its nuclear-related commitments.” Once again, this is in stark contrast with the current U.S. approach: not only has Trump been constantly ramping up its hostile rhetoric against Iran, but he also backed it up on May 8, 2018 by announcing the U.S. withdrawal from the “horrible” JCPOA – a decision that was openly criticized by the vast majority of the international community, including the EU and China, two of the key brokers of the agreement itself.

Thus, the 2018 joint statement confirms that, at least on paper, the EU and China are making decisive steps forward with regard to tackling the growing global governance void created by the United States, and that they have gained enough confidence to openly (and jointly) oppose Washington in a number of key domains. Of course, their relationship remains fraught with normative and policy hurdles, and it remains to be seen whether they will actually be able to capitalize on this largely U.S.-generated “negative momentum” to build up concrete (co-)leadership.

Francesco S. Montesano is Research Assistant to the Baillet-Latour Chair of EU-China Relations in the Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies at the College of Europe, Bruges