“China does not view its relations with North Korea as ‘lips and teeth’ anymore.” This kind of argument has been put forth by North Korea watchers for more than 10 years. In 2005, Anna Wu argued that “the traditional PRC-DPRK ‘lips and teeth’ relationship appears obsolete and self-destructive.” In 2013, Deng Yuwen wrote, “[B]asing China’s strategic security on North Korea’s value as a geopolitical ally is outdated.” In 2018, Zhang Feng believed that“the phrase of lips and teeth is just a geographic phrase for China” while Oriana Mastro also maintained, “China would not rescue North Korea if North Korea collapses.”

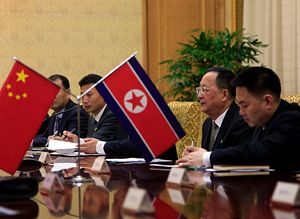

However, when Kim Jong Un made his first visit to China in March this year, China gave him far more prominence than any other visiting state leader, except for Donald Trump. The most senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials, including Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Qishan, and Wang Huning, all sat down and listened to Kim’s speech on the podium at the banquet. After the visit, one editorial of People’s Daily on March 29 highly praised the China-North Korean relationship as close “like lips and teeth.” The next two visits by Kim to China in the following two months further suggested that Beijing would never abandon this strategic ally.

So where did those earlier assessments go wrong?

The main problem is that deciphering China’s “lips and teeth” concept is not an easy task. The conventional interpretation is that China views North Korea as a junior brother and, due to this relationship, China would do whatever it could to assist North Korea economically, diplomatically, or even militarily. This interpretation, however, is misleading; the reality is that the “lips and teeth” relationship between the two sides has never worked this way.

The earliest record of China applying the phrase “lips and teeth” to describe its relations with North Korea was after the decision to intervene the Korean War. Chinese leaders decided to save North Korea in early October 1950. On October 24, Zhou Enlai first used this phrase to justify the geopolitical necessity of this military action at the Standing Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, stating that if the North Korean “lip” was gone, China (the “teeth”) would feel cold. Even back then, however, China did not support North Korea at any cost. The truth was China prioritized its own geopolitical imperative over North Korea’s wishes, which was reflected in the constant fights between the commander of Chinese forces, Peng Dehuai, and Kim Il Sung over the strategy and operations of the Sino-North Korean joint forces in the war. Joseph Stalin had to reconcile these arguments in person.

In other words, what really drove China’s behavior in the Korean War was Beijing’s own assessment of the connection between a degenerated geopolitical environment for China and the loss of a buffer against the United States — not a sense of brotherhood with North Korea. This is the key to understanding the “lips and teeth” relationship.

Normally, China does not use the phrase “lips and teeth” for every situation engaging with North Korea. The Chinese government has a set of default diplomatic rhetoric to characterize the Sino-North Korean relationship, such as “China and North Korea are connected by mountains and rivers,” “China and North Korea are intimate neighbors,” and “the parties, people, armies of both sides have a profound traditional relationship.” “Lips and teeth” is arguably the highest level of characterization. When China applies such a phrase, the context is often that North Korea is about to actively or passively deviate from China’s preferred trajectory. By emphasizing that “if the lips are gone, the teeth will feel cold,” China sends a message to outside audiences, as well as to North Korea, that North Korea is a buffer for China and that is something China will never compromise about.

Being a buffer for China means the existence of North Korea is China’s highest priority. From the end of the Korean War to the end of the Cold War, China seldom used the phrase “lips and teeth.” The lack of reference in this period was not because Chinese leaders had changed how they perceived the geopolitical value of North Korea, but mainly because they had not faced a situation where the survival of North Korea was endangered. The Sino-American rapprochement since the 1970s further concealed the China-U.S. strategic rivalry on the peninsula. When the Cold War ended, however, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and his successor Jiang Zemin were both very concerned that the rivalry would resume, and North Korea would likely be the next U.S. target of regime change. That was why, when the United States was ready to conduct a military strike on North Korea over the nuclear issue in June 1994, Jiang not only promised to send forces to defend North Korea but also emphasized in public when he met a visiting North Korean military delegation that “China and North Korea are cordial neighbors, like lips and teeth.” Andrew Scobell also demonstrated how maintaining the survival of North Korea drove China to initiate the Six-Party Talks in the second nuclear crisis 10 years later.

North Korea’s role as a buffer also implies China’s need to secure its ascendancy in North Korea. The 2000 visit between Kim Jong Il and then-U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was exemplary in this regard. Disregarding North Korea’s strong objection, China had decided to build diplomatic ties with South Korea in 1992. It did not provide much help to North Korea during the latter’s disastrous famine from 1994–98, either. However, the day before Albright and Kim Jong Il were about to hold their historic meeting, China suddenly sent a huge senior military delegation to North Korea for a high-profile celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Korean War. The meeting with Albright considerably paled in comparison. Chi Haotian, the vice chairman of the Central Military Committee, stated from Pyongyang that “China and North Korea are connected by mountains and rivers, like lips and teeth.”

Indeed, the chronic North Korean nuclear issue made Chinese deeply rethink the value of this North Korean buffer. The first North Korea policy debate in Chinese academic circles happened in 2006, the year that North Korea conducted its first nuclear test. The debate centered on the geopolitical value of North Korea — namely, is North Korea a strategic asset or burden to China? Scholars who believed North Korea was a strategic burden usually held a liberalist view, arguing China should make denuclearizing North Korea a priority to live up to the image of a responsible great power as well as protect the international nonproliferation regime. By contrast, those who saw the world through a realist lens still believed North Korea was a valuable buffer against the United States. This debate continues today, as shown by a furious exchange between Jia Qingguo, a professor at Peking University, and Zhu Zhihua, the vice chairman of the Zhejiang Association of Contemporary International Studies.

Over the years, more and more Chinese scholars have joined the liberalist camp, but leaders in Beijing seemingly remain in the realist camp. The best evidence is China’s long-held policy position on the North Korean nuclear issue that “no war” is prioritized over “no nukes.” China did agree with some United Nations Security Council resolutions on North Korea and did push North Korea harder than two decades ago. Nevertheless, this slight change is more from a prudent assessment that North Korea is economically strong enough to survive a little push than from a fundamental change in how China views North Korea.

Why is having a buffer so unshakable in the minds of leaders in Beijing? This buffer thinking is built on three critical factors:

1) The history of China and the Korean Peninsula — China’s stability has been inevitably influenced by wars occurring on the peninsula since the Tang Dynasty.

2) Geographical proximity — China’s capital Beijing is just few hundred kilometers away from the Sino-North Korean border.

3) The military reality that territorial conquest still determines the ultimate victor in modern warfare.

China’s discord with or even loathing of North Korea has not been much of a secret since day one. After all, China’s key concern with North Korea has never been whether it is a friendly neighbor or a vibrant economy, but that it is a buffer keeping the United States out of the peninsula. This buffer thinking, embodied in the phrase “lips and teeth,” would ultimately trump any other concerns from a tactical level, as long as the specter of a U.S. military presence lingers along the bank of the Yalu River.

That is how China’s “lips and teeth relationship” works.

Yu-Hua Chen is a Ph.D. scholar at the School of Culture, History, and Language at the Australian National University (ANU).