On July 3, the Cabinet of the Japanese government approved the country’s 5th Strategic Energy Plan after receiving the final draft the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). The plan is significant as it sets forth the government’s approach to energy policy for the future and is considered one of the key documents indicating the government’s direction with respect to national energy supply and energy markets. It is closely watched by the corporate and civil sectors alike both home and abroad.

The Japanese government is required by law to reevaluate and issue a strategic energy plan at least every three years and, while it is not a binding legal instrument, it has become a de facto policy tool that has been followed by the various government agencies and departments in each of its iterations. It also serves as a market signaler and seeks to provide long-term certainty to energy market participants and allay any fears of a sudden policy shift.

Future Energy Mix

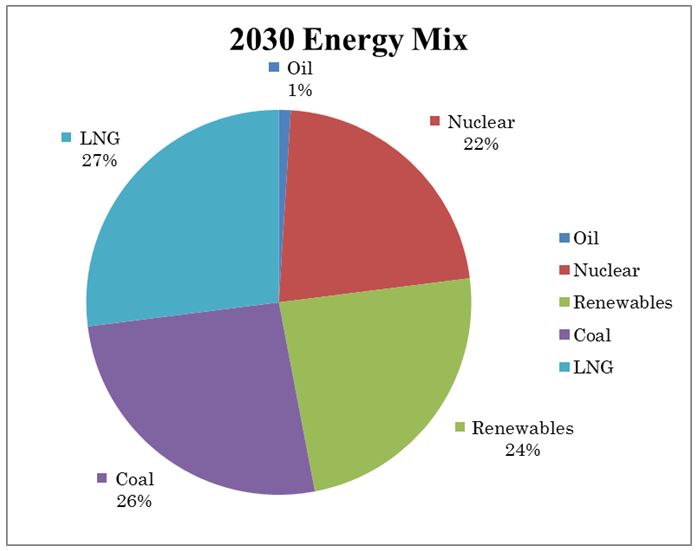

A key element of the strategic energy plan is the government’s future energy mix predictions, with the current benchmark date being 2030. In the plan, METI maintained the same energy source ratio for 2030 as it had outlined in the previous strategic energy plan in 2013 and in its long-term energy supply and demand outlook issued in 2015. The desired energy ratios set forth a balanced approach to the full range of power generation options, including both renewables (22 to 24 percent) and nuclear (20 to 22 percent).

Note: The percentages provided in the Plan for Renewable Energy and Nuclear Energy were 20-22 percent and 22-24 percent, respectively. For the purposes of this chart, the higher of the range of percentages has been used.

While the ratios have remained the same, what is new is that renewable energy sources were designated as a “main source of power generation” for the first time. Some see this as a major shift in government policy that recognizes that in the future renewable energy has a role to play as a baseload power source and not only as auxiliary power. As it currently stands, renewable energy in Japan accounted for 15 percent of the energy mix in 2017, up from 10.7 percent in 2010. Renewable energy proponents are encouraged by the upward trend in market penetration but also consider that Japan could do more to extend the 20-22 percent target for 2030, especially as the renewable energy target is significantly lower than similar targets set by other G7 countries.

The Future Challenge of Nuclear and Coal Power

The plan makes it abundantly clear that the Japanese government still sees nuclear power as playing a significant role in the energy market as well as being an important method of meeting its environmental commitments. However the resumption and expansion of the nuclear power industry in Japan remains controversial.

Following energy demand predictions, to reach the proposed level of nuclear generation in the overall energy mix, it becomes clear that new nuclear reactors will need to be constructed in addition to all of Japan’s existing nuclear reactors being restarted and having their operational life extended.

The stigma of nuclear power runs deep and strong as reconstruction efforts from 2011 are still underway and fearful local communities have successfully campaigned to block the restarting or construction of new reactors. Cases have been filed with respect to most nuclear power plants, with residents and citizen groups seeking injunctions from the courts to block any decision to restart the reactors. Multiple suits are underway across the country with appeals being heard on a regular basis but no conclusive position has yet been determined. In addition to grassroots movements, prefectural governors have openly come out in opposition to the national government’s plans to restart the reactors in a bid to gain public favor as local election season begins.

Clearly, this level of opposition puts the government’s proposed energy mix in jeopardy as questions are raised over whether the government will be able to implement the measures necessary to reach the proposed percentages.

In such a climate of uncertainty over the future of the nuclear industry, utility operators too are skeptical. In the wake of the Fukushima disaster, nuclear reactors were shut down and utility companies turned to large-scale thermal coal power plants to make up the shortfall. As a result, as the share of nuclear power fell from 28.6 percent in 2010 to nil in 2014, thermal coal power rose from 25 percent to 31 percent over the same timeframe. In the last two years to date, eight new power plants have come online and 36 new projects are scheduled to come online in the next decade, which will increase total coal power generation capacity by approximately 40 percent. The upward trend in coal generation is at direct odds with the Plan’s forecast of coal generation falling from its current share of approximately 30 percent to only 26 percent of total energy generation.

This too is out of step with other major economies around the world such as the U.K., which plans to shutter all coal-fired power plants by 2025, and France, a former nuclear power heavyweight, which plans to cease coal power generation by 2021.

With that in mind, similar to the nuclear industry, the feasibility of increased coal generation is being questioned. International and domestic pressure is mounting for a more balanced approach to be adopted. Environmental groups, using the Paris Agreement as justification for their opposition, and local citizen groups have been mobilizing against the construction of new coal power plants. Local citizen groups in Chiba and Hyogo Prefectures have recently successfully forced utility operators to completely abandon construction plans for several new large scale power plants. Three of Japan’s mega-banks, Mizuho, Mitsubishi-UFJ Bank, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, also released over the past two months new lending policies that will significantly restrict the amount of finance that they will make available for new and existing coal generation projects.

While the Strategic Energy Plan is designed to give energy market participants policy certainty, the latest iteration has thrown up more questions than answers. The feeling is that the pro-nuclear and pro-coal position of the ruling government is out of step with what is practically achievable given the changing community and business landscape. Maintaining the status quo of the 2014 and 2015 predictions is intended to give a sense of continuity but, given concerns over changes in context and evolving situations that may pose significant problems to the achievement of those targets, doing so may have instead only contributed to an already unpredictable outlook.

Peter Bungate is an Australian corporate lawyer working in Japan since 2014, specializing in energy markets and policy both domestic and international.