Editor’s Note: On August 25, 2017, Rohingya militants attacked police posts in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. Myanmar’s security forces responded with a brutal campaign of violence against the largely Muslim ethnic minority, including mass executions, rape, and the burning of villages. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, where many still linger in refugee camps.

A year after the crackdown began, Matthew Wells, a senior crisis advisor at Amnesty International, analyzes satellite imagery of one Rohingya village in Myanmar and one Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh. The changes visible on the ground hint at the uprooting and exile of a people.

Kan Kya (South): A Rohingya Village

Kan Kya (South) is a Rohingya village in the Myo Thu Gyi village tract, near Maungdaw Town. On 21 January 2017, satellite imagery shows the village intact, with a road running through its northern part and a canal along its southern edge.

Satellite imagery captured on September 16, 2017 corroborates witness testimony that most structures in the village were destroyed by fire. We know that, during this period, the Myanmar security forces burned at least several hundred Rohingya villages across northern Rakhine state. Led by the Myanmar Army, the security forces carried out widespread burning in a deliberate and targeted manner, razing Rohingya homes, mosques, and shops. In Kan Kya (South), only a few structures remained intact, mostly in the southeastern part of the village, near the canal.

By April 26, 2018, satellite imagery shows that Kan Kya (South) has been cleared; the structures that survived the initial burning have been removed, along with the burnt remains of homes and other buildings. We know, from the Myanmar government’s own statements and from satellite images and aerial photographs, that the authorities have overseen the bulldozing of dozens of Rohingya villages, particularly in Maungdaw Township.

The image from April 26, 2018 also confirms the presence of at least 19 new structures, most of them long rectangular buildings with red roofs. The new structures are surrounded by a perimeter fence, which is similar to the fencing found around known security force bases, and the layout and organization of the buildings is almost identical to those in known Border Guard Police (BGP) bases. A reliable source living in that area told Amnesty International that the construction was for a BGP base, which government officials acknowledged during a media tour, as reported by The Irrawaddy in April. The BGP base is being built directly on land where the Rohingya used to live.

What we see in Kan Kya (South) is happening in other Rohingya villages across northern Rakhine State. The Myanmar authorities have overseen frenetic change in recent months, bulldozing Rohingya villages and constructing new security and civilian infrastructure in their place. These actions contradict Myanmar’s commitment that Rohingya refugees will be able to return to their original places of residence. More generally, safe and voluntary returns will not be possible until there is justice for the security forces’ atrocities against the Rohingya and until the Myanmar authorities dismantle the system of discrimination and segregation that has existed for years in Rakhine state.

Kutupalong Refugee Camp

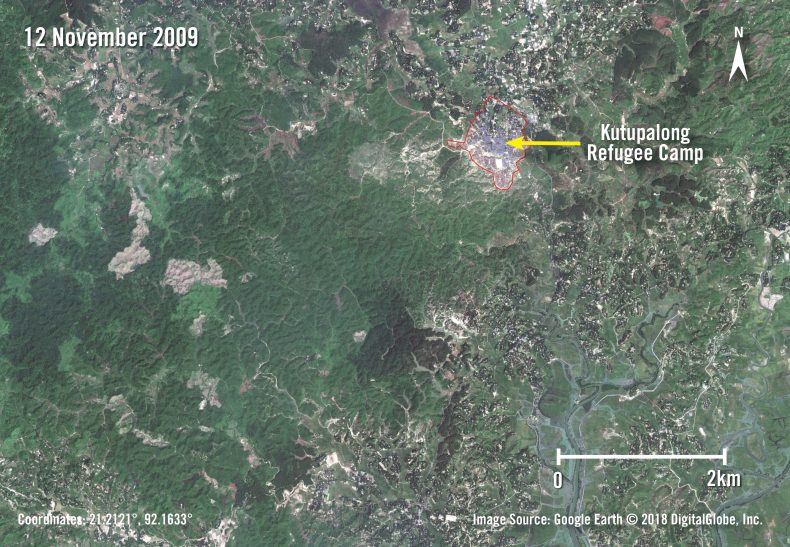

Satellite imagery from November 12, 2009 shows the oldest part of Kutupalong Refugee Camp — an area that has housed and continues to house Rohingya refugees who were forced to flee to Bangladesh long before the current crisis. It’s a reminder that the Myanmar military’s violent expulsion of Rohingya women, men, and children did not begin on August 25, 2017. Several hundred thousand Rohingya were pushed out of northern Rakhine state and into Bangladesh in both 1978 and in the early 1990s. Most eventually returned to Myanmar, many under conditions that raised concerns about how voluntary their decision was. The same mistakes must not be repeated this time.

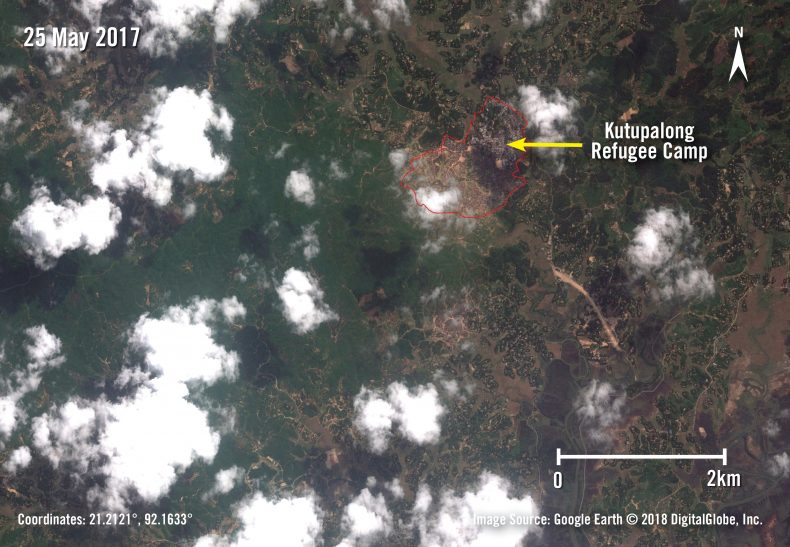

By May 25, 2017, we can see that Kutupalong has grown, mostly to the southwest. Tens of thousands of Rohingya were forced to flee Rakhine state starting in October 2016, after the Myanmar security forces launched brutal “clearance operations” following attacks on police posts by a Rohingya armed group now known as ARSA. The Myanmar military committed widespread and systematic human rights violations, including unlawful killings, rape and other forms of torture, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary detentions. Several investigative commissions established by the Myanmar authorities in effect whitewashed the crimes, leading to no accountability for crimes against the Rohingya. That impunity helped set the stage for the atrocities that the security forces have committed during the last year.

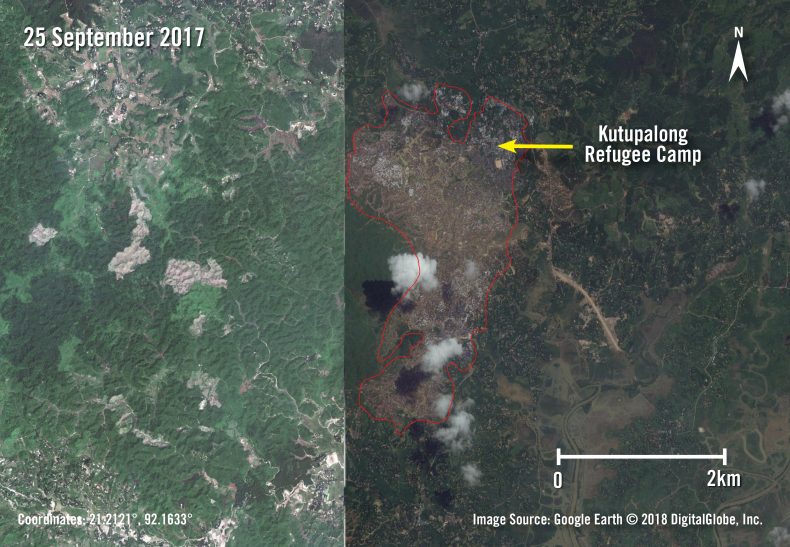

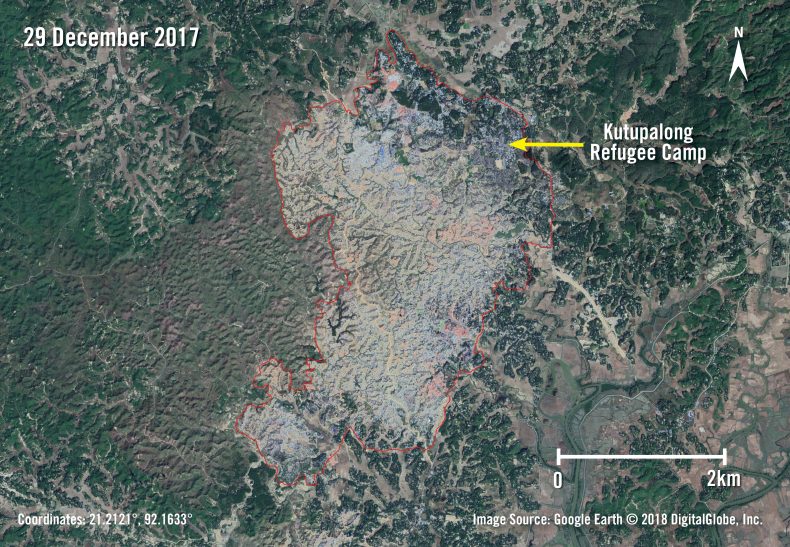

In the September 25, 2017 and December 29, 2017 images, we see the incredibly rapid expansion of Kutupalong as a result of the Myanmar military’s ethnic cleansing campaign. White, red, and blue tarpaulin roofs are densely packed across an area that stretches for kilometers. By September 25, only a month after coordinated ARSA attacks on security force posts, the Myanmar military’s killing, raping, and burning across northern Rakhine state had forced more than 480,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh. The most recent estimates indicate that more than 705,000 Rohingya women, men, and children have fled since August 25, 2017, joining several hundred thousand Rohingya refugees who were already in Bangladesh. Kutupalong Balukhali Expansion Site is now the largest refugee camp in the world, housing 626,000 people.