Xi Jinping has a global vision for China and has centralized foreign policy around himself and the CCP. In this six-part blog series, MERICS researchers take a closer look at the (new) setup of China’s foreign policy leadership, institutions, budget, and personnel – as well as on its policy approach to Europe. This is part 4; see part 1 of the series here.

To support their global ambitions, China’s leaders have stepped up resources for foreign affairs since the early 2000s, a domain previously underfunded and often overlooked by the highest party echelons. So how is China’s step-change on the world stage reflected in its financial accounts?

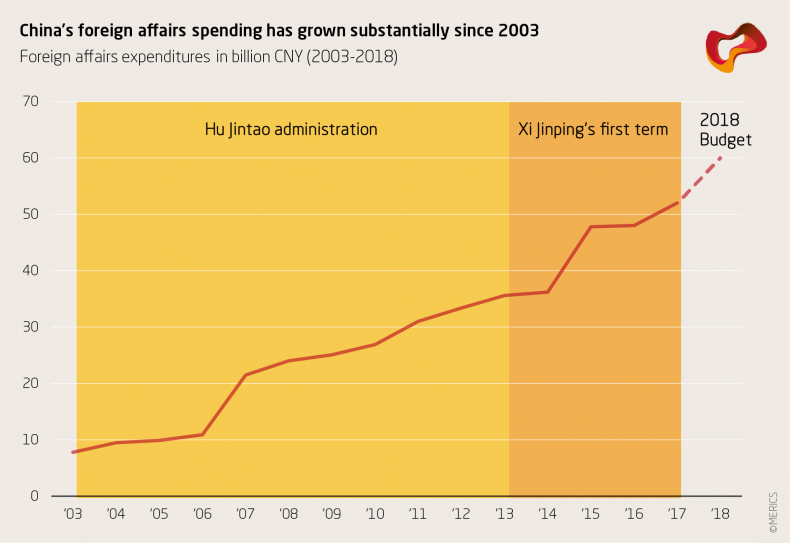

Over the course of the past 15 years, each year the Chinese government spent more on foreign affairs than the year before. Between 2003 and 2017, China’s foreign affairs expenditures rose at a 14.5 percent compounded annual growth rate (CAGR), hence almost at the level of China’s breakneck GDP growth rate of 15.3 percent CAGR over the same period.

Comparing the end of the Hu period in 2012 ($5.2 billion) and the end of the first term of Xi in 2017 ($8 billion), resources spent on foreign affairs almost increased by two-thirds. Despite a slowing down of GDP growth between 2016 and 2017, China’s 2018 budget envisages a spending increase of 15 percent.

The comparison of the Hu presidency (2003-2012) and Xi’s first term (2013-2017) reveals that spending growth had been more accelerated under Hu at a 17.5 percent CAGR (2003-2012), while spending growth under Xi slowed to 9.9 percent CAGR (2013-2017).

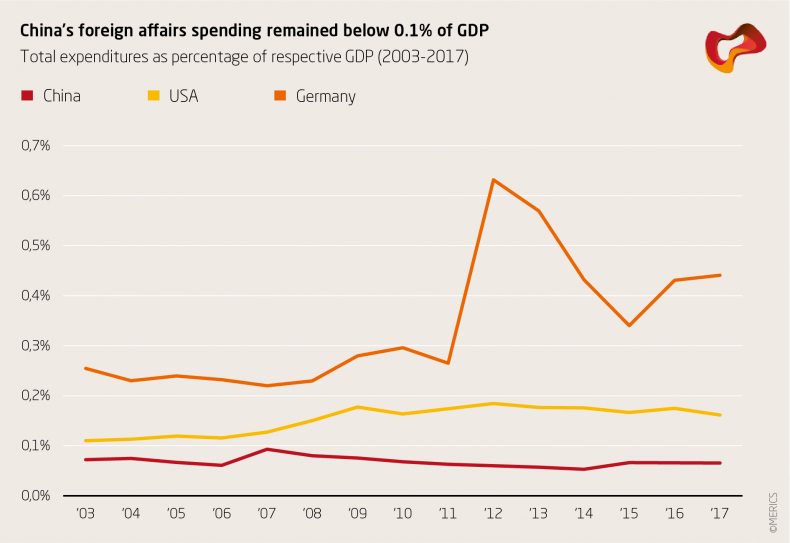

However, contrasting these growth figures with the GDP growth rates of the respective periods shows that the Chinese government’s resource allocation for foreign affairs under Hu was quite conservative in the face of the historically fast GDP growth (CAGR 20 percent). On the contrary, foreign affairs resource investment during Xi’s first term was maintained at a level substantially above GDP growth, with the latter slowing down to CAGR 6.2 percent.

Overall, the scaling up of foreign affairs resources under Hu arguably took place in a catch-up mode to enable China’s growing international participation, whereas Xi has been working on taking China’s foreign policy to the next level — as indicated by the newly created Central Foreign Affairs Commission (see part 2 of this series) and the promotions of Yang Jiechi and Wang Yi — with the intent of shaping international affairs according to China’s own visions and priorities.

China’s Foreign Affairs Spending Is Less Than Meets the Eye

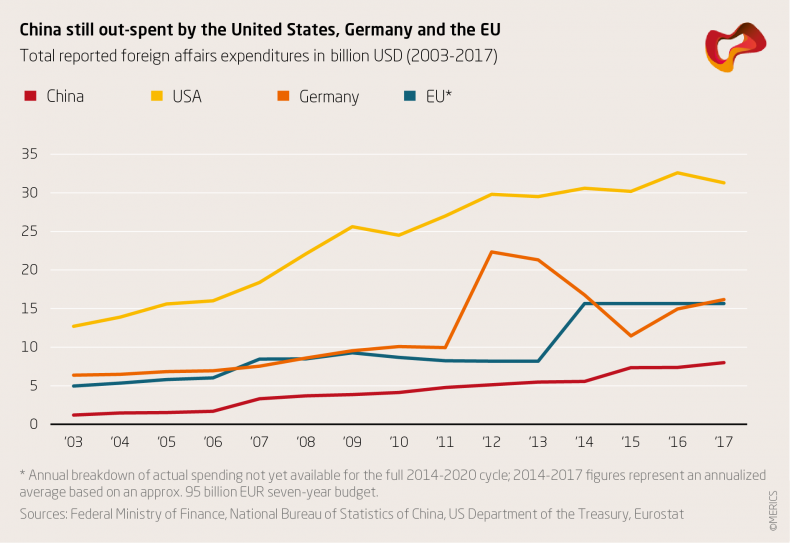

However, the rapid increase in China’s foreign affairs spending needs to be put into perspective. First, comparisons to other countries’ foreign affairs expenditures make China’s foreign affairs expenditures look more modest. Although the growth of China’s foreign affairs expenditure between 2003 and 2017 (CAGR 14.5 percent) was substantially higher than the respective growth in the United States (CAGR 6.7 percent) or Germany (CAGR 6.9 percent), China’s foreign affairs spending as a percentage of GDP still trails both those countries’.

Likewise, in absolute 2017 figures, China’s foreign affairs budget (approximately $8 billion) still lags both behind Germany’s ($16.2 billion) and the United States’ ($31.3 billion), and is also a wide margin behind that of the EU institutions (94.5 billion Euros for 2014-2020, corresponding to approximately $15.7 billion per year), which merely complements the individual activities of EU member states.

Second, despite the seemingly high expenditures, foreign affairs still were not high on the Chinese list of priorities. Foreign affairs spending growth for 2003-2017 (CAGR 14.5 percent) remained slower than overall government spending growth (CAGR 16.3 percent) over the same period.

As a consequence, the share allocated to foreign affairs in China’s total government spending actually declined from 0.32 percent in 2003 to 0.26 percent in 2017. In contrast, over the same period, key domestic spending buckets such as social security and employment (CAGR 23.7 percent), public health (CAGR 23.3 percent) or education (CAGR 18.1 percent) grew a lot faster.

In sum, these findings suggest there is still substantial room for China to catch up before it reaches the foreign affairs spending level of other countries. This catch-up is underway, with higher spending growth rates than those in the United States or Germany.

Difficult Trade-Offs Between Domestic and Foreign Priorities

Xi has started to demonstrate his foreign policy ambitions, but he also has to balance them with slowing growth and rising domestic spending obligations. In order to overcome the “middle income trap” and pursue continued economic development, China is required to sustain substantial funding for critical domestic policy goals (e.g. “moderately prosperous society by 2021,” “Made in China 2025,” “Healthy China 2030,” as well as PLA modernization, environmental protection, educational reforms) in the longer term. Decisions in favor of even more foreign affairs resources become particularly sensitive trade-offs.

However, in face of not only the Trump administration’s “America First” policy, but also the EU aspiration to become a more important global player (with its recently announced substantial 30 percent external action budget increase), the Chinese government is likely to continue scaling up its foreign affairs spending to use the geopolitical openings left by the United States’ retreat from multilateral formats – and to secure its influence in an increasingly multipolar world.

Markus Herrmann is a visiting academic fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) in Berlin, Germany. He is also the co-initiator of the Asia program by the Swiss foreign policy think-tank foraus.

Sabine Mokry is a research associate at MERICS.

Some caveats for the use of official Chinese data

This analysis relies on Chinese government sources, in particular on the annual accounts of the Chinese government expenditures published the by National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS).

To facilitate reading, this blog post uses the so-called Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) indicator, which focuses on the growth trend via annualized growth rates and eliminates growth fluctuations.

The following specific methodological points need to be flagged:

- Foreign affairs spending comparisons across countries are inherently problematic, as organizational, accounting, and political labeling practices vary.

- Accounting or budgeting methodologies may have changed over time.

- Currency conversions were made at a 6.5-to-1 USD to CNY rate and 1.16-to-1 EUR to USD.

- For 2018, earmarked budget figures were used.

Although a lot of China’s international activities, e.g. infrastructure funding, defense activities or party diplomacy, are not formal part of the published foreign affairs expenditures, looking into “classical” Chinese foreign policy government expenditures can still provide an important pointer for assessing the nature of China’s current and future global reach.