Salisbury Cathedral in peaceful Wiltshire in the United Kingdom would seem to be an unlikely place to find a symbol of how trade relationships can turn nasty, and then violent.

But in a leisurely stroll through the magnificent 13th century building, boasting the tallest spire in Britain, one suddenly comes across an incongruous reminder of the truth that trade and war are often inextricably linked.

In Salisbury Cathedral are hung, in pride of place, two regimental flags of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Wiltshire Regiment. Beautifully embroidered into the flags are the place names in which the regiment served, memorializing the men and the campaigns they prosecuted. Sevastopol, South Africa, Sobraon, among others — and then, “Pekin 1860.”

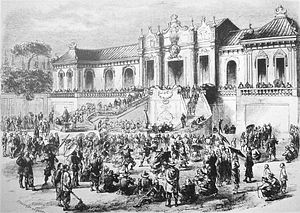

“Pekin 1860” refers to the end of the Second Opium War, which was decided very much in favor of the English and French forces of the day. The Chinese defeat resulted in the looting and burning of the Summer Palace outside of Beijing, and culminated in total capitulation by the beleaguered Qing Court to Western demands for trading rights and ports. Indeed, it can be argued that this event, and Britain’s overall complex relationship with China, has had more influence on China’s disillusionment with Western powers than that of any other single nation.

While the U.K. today does not openly crow about the treasures it took home from China, neither does it flinch. Indeed, Britain proudly displays, in some of its most landmark institutions, spoils and memorabilia of the wars and conflicts that expanded, extended, and enforced where necessary the rule and role of the trading relationships of the British Empire.

Writing in Oxford Today, Tiffany Jenkins states that “the Chinese government estimates that about 1.5 million items were taken” from the Summer Palace. The loot is housed across the United Kingdom, from the British Museum to Windsor Castle, from the Victoria & Albert to the Royal Engineers Museum at Chatham in Kent.

Such behavior is hardly isolated. Few nations that have sought assertive, even acquisitive, and often avaricious trade relationships with nations far-flung from their own shores have been able to maintain and sustain those relationships without the firm backing of military might. Along with the British, the examples of the Spanish, Ottoman, and Dutch empires come to mind; all used military force to varying degrees of success both to open trade and to secure it once established.

Trading relationships often begin benignly, and with good intentions. But relationships sour and can turn deadly, as the history behind the regimental flags in Salisbury Cathedral shows. The most dangerous flash points occur when trade, and often the ensuing investments, occurs between two nations of unequal power. Such was the case with Britain and China in the 19th century.

Will this be the case between China and the trading relationships it is building under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)?

China, unsurprisingly, adamantly claims no. In line with the deep cultural disgust which most Chinese today have toward the ideas of hegemony, imperialism, and the worst of all, colonialism, Xi Jinping and the Chinese government reiterate to all who will listen that China’s goals are peaceful and for the mutual and equal benefit of all partners in the relationships. And many are listening. As Shannon Tiezzi wrote recently in The Diplomat, China is making concerted “attempts to shed accusations of ‘neocolonialism’ once and for all.”

Chinese diplomatic representatives have been a little more grandiose about China’s expanding global role, however, perhaps in more unguarded moments. Upon the occasion of the first visit of Chinese warships to London in October of 2017, the Chinese ambassador to the U.K., Liu Xiaoming, not only quoted Churchill (“Continuous effort, not strength or intelligence, is the key to unlocking our potential.”), but added: “To meet the challenges and uphold peace, China proposes to build a community of shared future for mankind, [and] calls for a new type of international relations.”

Liu’s words, spoken on the occasion of a military first for China, offer a window into the degree of China’s current ambitions. “China” will build a community for all of mankind. “China” wants a new type of international relations.

China’s increased confidence and success in pursuing trade, investment, and military opportunities at great distance from its traditional comfort zone have all the hallmarks of the similar ambitions that drove nations of yore to reach beyond their sovereign territories for wealth and power. Logic would dictate that China’s experience as the victim of such overreach should restrain it from similar behavior. Sadly, and all too often, however, the abused become the abusers. It remains to be seen whether China can escape the traditional historical trap into which others have fallen.