Six major interlocking themes coincided this week: China, Afghanistan, Xinjiang, Russia, the September 11 attacks in the United States, and the U.S. -China trade war.

The first of these themes is the China-Afghanistan relationship. There are few ironies of international relations to match the unlikely collection of actors that, every generation or so, find themselves supporting the same side in Afghanistan’s sad and unceasing turmoil.

Now that it is confirmed by Reuters that China is indeed planning to train Afghan soldiers on Chinese soil, China finds itself once again more firmly on the same side as the United States, NATO, and other nations attempting to tackle the problem of terrorism emanating out of Afghanistan.

Once again?

It is worth recalling that the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union prompted an international response to support the indigenous mujahideen groups that formed to fight the Soviets. Chief among the nations supplying money and arms by 1980 were the United States, Pakistan, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and, secretly, the U.K.

To put the relationships among those countries into context, in 1980, China and the United States had only just established full diplomatic relations after a schism of 40 years. China and Saudi Arabia did not have diplomatic relations at all, and wouldn’t until 1990. In 1980, Iran had captured and was holding 52 Americans hostage at the American Embassy in Tehran, and Iran and Saudi Arabia were barely speaking, on the heels of Iran’s verbal attacks on the very essence of the legitimacy of Saudi Arabia’s ruling family.

Yet all of these nations, each for its own purposes, supported fighters who would one day become the Taliban, who in turn would later foster and provide support to al-Qaeda.

China, though, was perhaps the most surprising of the major supporters of the Afghan mujahideen. In 1980, China was poor, with an economy ravaged by decades of mismanagement and incompetence. Economic reforms had only nominally begun, and had had no discernible effect yet. The effects of the Cultural Revolution were still being felt at all levels of Chinese society. And China was still very much a closed society, and country.

Yet, over the next several years, China would train anti-Soviet Afghan mujahideen forces, and provide millions of dollars of weaponry to them.

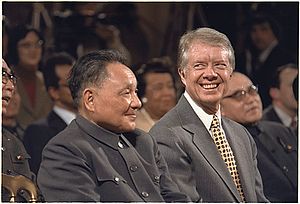

And, also in 1980, China would, incredibly, receive military support from the United States to combat the threat from both the Soviet Union and Afghan Communists. In a move designed to bolster the new diplomatic relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China both for its own value, as well as to counter the Soviet Union, the Carter administration not only sold China military equipment, it also extended Communist China most-favored nation trading status.

That status led to yearly U.S. congressional reviews of China’s human rights record, and eventually, to U.S. support for China’s successful bid to join the World Trade Organization. Today, the United States and China are in ever-widening trade war.

What were the threats to China that led it to support the Afghan mujahideen, and to buy military equipment from the United States? The first was nothing less than the installation of a Soviet communist government in Afghanistan, precisely the same Soviet communism that had inspired, molded, and nurtured China’s own Communist Party and revolution in the first place.

The path from China’s embrace and acceptance of Soviet communism from the 1920s forward, to its complete repudiation of the Soviets themselves in the 1950s, is an oft and well-told story. The key takeaway, however, is that the split was so decisive, and so final (one thought), that China could turn its back on its former mentor, accept assistance from its former nemesis, the United States, instead, and actively oppose the installation of a communist government in another of its border neighbors that by logic it should have welcomed.

So much for communist brethren and the Internationale.

China’s greatest fears and motivation, though, in 1980 and now, all center on unrest and a perceived threat to overall national security arising out of Xinjiang. The traditionally majority-Muslim province has been a source of pronounced concern for Beijing for decades. The Chinese Communist Party’s response has been multipronged. From saturating populated areas with Han Chinese migrants, to restricting and repressing the practice of Islam, Beijing is clearly on a mission to de-Islamify Xinjiang.

And now, from Human Rights Watch to a major New York Times story, reports are flooding in that China and its Communist Party are engaged the forced re-education of up to a million Uyghurs of Islamic faith in detention camps in Xinjiang– a practice eerily reminiscent of concentration camps and ethnic cleansing.

The news of China’s renewed and upgraded military support for Afghanistan, combined with the revelations of its increasingly draconian policies in Xinjiang, all occur under the backdrop of the remembrances of the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, carried out by Islamic terrorists with links to Afghanistan. Thousands of ordinary Chinese flocked to the American Embassy in Beijing, leaving flowers and notes of condolence. That attack launched the U.S. Global War on Terror – and China eagerly reframed its Xinjiang policy in those terms, as it has ever since.

The denouement to this story is that this week sees a return to dramatically heightened Chinese- Russian relations. Not only are Chinese troops participating in Russia’s largest-ever military exercises but President Xi Jinping of China joined Russia’s Vladimir Putin at the Vladivostok Eastern Economic Forum, as well. They flipped pancakes and presumably had some substantive discussions, too.

The world has changed since 1980, but the events of that year are still echoing today — in Afghanistan, China, Russia, and the United States.