Japan doesn’t boast a long history of space innovation and it’s not a country that springs to mind when you think of space travel. But the government is determined to make up for lost time by boosting space development and prioritizing a rapidly growing space industry.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) unveiled plans to develop manned spacecraft for moon landings in 2020, to have completed by 2030. But first, an unmanned moon probe will be launched in fiscal year 2021. If successful, both missions will be firsts in Japanese history, and the first manned landing on the moon in 60 years, since the U.S. Apollo missions.

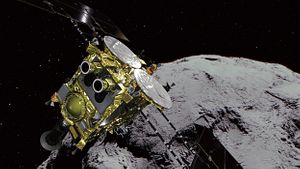

Under the first project, JAXA’s first unmanned lunar landing aircraft, SLIM, will be launched on a H2A rocket with its sights set on a small lunar crater on the side of the moon. The low latitude area was chosen for the exposure of olivine mineral stone, which could unearth a better understanding of the origins and history of the moon. JAXA project manager Shinichiro Sakai says pulling off Japan’s first two-part lunar landing is a nail biting responsibility as the accuracy of SLIM’s first unmanned landing is expected to be applied to the second, manned mission.

But JAXA’s prized moon landing could be beaten by private startups like Tokyo-based Ispace, which are also contending for a place in Japan’s history books with plans to launch a lunar orbiter and a rover in the next two years. Their ultimate goal — to provide commercial transportation to the moon and construct a mining plant to identify the moon’s resources — caught the attention of Google. That opened the door to raising $90 million from mainly Japanese companies such as advertising giant Dentsu, Japan Airlines, Suzuki Motors, and the Development Bank of Japan, which all want a piece of this new frontier. Ispace CEO Takeshi Hakamada said while their carry load of 30 kilograms is no match for the government-backed mission, with a 100 kilogram capacity, they’re happy government investment is advancing technology and bringing down costs.

The most notable Japanese space inventions currently in research and development include a robotic space “arm” capable of catching and removing high-speed space junk, a space elevator connecting earth and the space station by cable, and a satellite observing the earth’s overall carbon monoxide and methane concentrations to help prevent global warming.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology’s fiscal year 2019 budget draft requested 55.3 billion yen (roughly $500 million) for space exploration, an increase of 31 percent compared to the year before. Included in the calculations is whether Japan can secure an advantage in international space exploration, which is already centered on the United States.

The global race for space supremacy also has undeniable defense applications. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has plans to boost Japan’s defense capabilities in “unconventional” fields such as outer space and cyberspace. Abe has said it is “impossible to protect our country from every threat if our thinking is limited to conventional categories of land, sea and air.” The new space threat identified in Japan’s defense guidelines will undergo close examination from an advisory panel this week, who will discuss the nation’s defense objectives over the next decade.

Ibaraki prefecture, north of Tokyo, has hit the ground running in preparing for the future of space innovation, announcing a five year joint “Ibaraki Space Business Creation Base Project” with JAXA and the government with the hopes of establishing a home base for the Japanese space industry. Tsukuba city in Ibaraki will build and staff a support center to connect space-related startup companies and investors interested in rocket and satellite development to foster new industry ideas.

While the United States takes the lead in space travel and rocket development, Japan’s space industry vision for 2030 mapped out in May sets out a target of doubling the market scale from the current 1.2 trillion yen.