Two weeks ago, high school students across Cambodia sat for their national exams. It has been four years since stringent anti-cheating reforms were introduced, which resulted that year in more than 70 percent of students failing their exams. This multifaceted push for reformation, spearheaded by Education Minister Hang Choun Naron, aims to improve an education system still recovering from the Cambodian genocide.

Four decades ago, from 1975-1978, the Khmer Rouge conducted a genocidal campaign, killing between approximately 1.2 to 2.8 million Cambodians — one-quarter of the country’s population. During this senseless violence, more than 90 percent of the country’s financial and educated elite were targeted and killed.

Before the civil war that began in 1970 and ended with the Khmer Rouge taking power, Cambodia had undergone a stunning educational transformation. After independence from France, Prince Sihanouk had made education a priority, spending more than 20 percent of all government expenditures on education. Taking inspiration from French and Buddhist education systems, Cambodia was the model of education in the region: education attainment rates grew steadily at a remarkable rate of more than 2 percent.

Prince Sihanouk was deposed in 1970, just 17 years after Cambodia gained independence, and the country was embroiled in conflict for the next two decades. A five-year civil war was followed by the Pol Pot-led genocide. Schools were shut down and were replaced by reeducation and ideology camps. Research by Thomas Clayton finds statistics from the Ministry of Education that 75 percent of all teachers and 96 percent of all tertiary students were killed.

While the Cambodian genocide ended on December 25, 1978 when Vietnamese soldiers and Cambodian rebels reentered the country, it was not until 1991 that peace accords were signed and reconstruction efforts could begin. While the new government initially attempted to allocate more than 15 percent of the national budget to education, this figure dropped to 8 percent within three years. According to a 2001 International Labor Organization report, only 25 percent of respondents reported the completion of secondary school or higher, and almost 20 percent responded that they had never received any schooling at all.

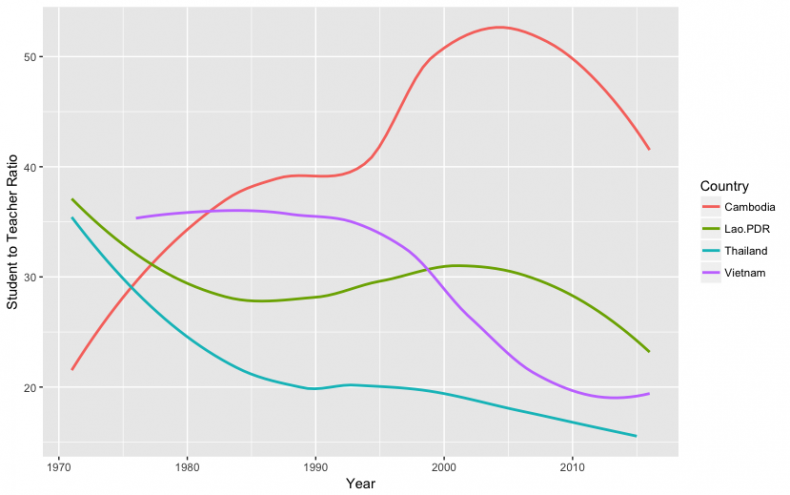

An immediate impact of the dearth of teachers is a high student to teacher ratio. Data on regional student to teacher ratios from the World Bank demonstrates the sharp increase in student to teacher ratios in Cambodia starting in 1970. The increase continued until the early 2000s, at which point there was a relative turnaround. The rise, even after the peace accords in the early 1990s, is attributable to more children entering school rather than teachers leaving schools. It’s emblematic of the difficulty of recreating institutions: the better the institutions become, the greater the public burden placed upon them.

What’s remarkable about the student to teacher ratio is that the Cambodian government had the capacity and wherewithal to stop the educational decline from becoming truly disastrous. After the genocide, Cambodia had an enormous shortage of teachers, facilities, and funding while illiteracy rates skyrocketed to almost 40 percent.

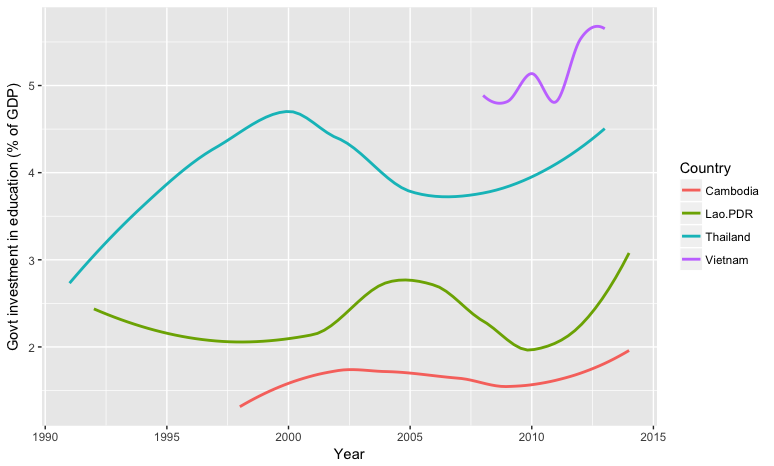

Cambodia still has far to go to reach even pre-war education standards, but the recent reforms by the new Education Minister are steps in the right direction. His move to pay teachers more, bringing their monthly salary to an average of almost $300 per month, might help address the high student to teacher ratio. Cambodia’s current ratio, especially compared to regional averages, denotes a high level of inefficiency within the school system. Data from the World Bank on expenditures on education as a percentage of GDP visualizes the gap.

Although increasing funding is a seemingly requisite condition to increase the quality of education in the long run, purely increasing government expenditures may not be enough to immediately catalyze growth. High rates of students living in poverty decreases students’ abilities to learn, but constitutes an entrenched problem reaching outside the classroom. Still, considering that the modern Cambodian education system arose out of a completely decimated system, the progress so far is surely commendable. So as more than 100,000 high school students across Cambodia await their test results, there is certainly reason for optimism about the education system.

Tyler Headley is a research assistant at New York University. His work has previously been published in magazines including Foreign Affairs and The Diplomat.