At the end of the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” was written into the Party’s constitution. Included in Xi’s political theory was the statement that “”Improving people’s livelihood and well-being is the primary goal of development.”

The Chinese government has been remarkably effective at creating wholesale development and lifting entire populations out of poverty. Research by Gallup suggests that the poverty rate in China fell from 26 percent in 2007 to 7 percent in 2012. But while improving livelihoods and reducing poverty are laudable goals, there may be an ulterior motive to continue bolstering the economy: new evidence suggests that slower economic growth rates in China correlate with higher rates of protests.

In a non-democratic regime, one of the few ways for the populace to remove a political institution is through mass mobilization. The recent Arab Spring movement, which resulted in regime changes in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, demonstrates the catalytic potential of protest movements. These types of generational protests are relatively rare: the last major protest in mainland China — the 1999 Falun Gong protests at Zhongnanhai – occurred more than 20 years ago.

While large-scale protest movements in mainland China may be rare, smaller strikes and protests have grown markedly more frequent in recent years. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimated in 2006 that there were more than 90,000 “mass incidents,” or protests. Causes for protests include forced demolitions, ethnic minority struggles, pollution, and labor disputes. There have been notably few protests for democracy, and the last string of pro-democracy protests in 2011 were met with a government crackdown.

The fierce response by the Chinese government to pro-democracy protests indicates that these are perceived as existential threats by the CCP. Workers strikes, on the other hand, are less likely to be met with a crackdown but can still pose a threat to overall political stability: strikes and protest can generate market uncertainty and decrease the productivity of the businesses whose workers are on strike.

There is also the potential that a labor strike can foment into large-scale protests. The Tunisian protests that led to the overthrow of the government began with a single vegetable peddler’s cart being confiscated by the police. A snowballing effect occurred: upon the vendor’s self-immolation, peaceful protests turned to riots, foreign news reports about the regime’s corruption catalyzed more outrage, and ultimately the president was forced out.

Thus, while labor strikes and workers protests may normally be benign and do not typically lead to regime-changing demonstrations, the latent possibility of a snowballing effect makes them a priority for the government. And in China, workers protests are becoming more frequent.

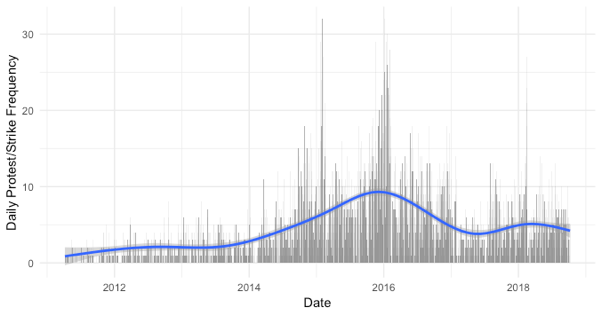

Data on daily protests and strikes from the China Labor Bulletin, a nonprofit organization based in Hong Kong, demonstrates the rising distribution of strikes over the last seven years. The data isn’t perfect: the group notes that because it only picks up protests and strikes reported on social media or from official sources, they probably collect 5-10 percent of collective worker action. Similarly, because their sampling rate may change over time, the China Labor Bulletin cautions against comparisons across time.

While trends must be taken with a grain of salt, due to a scarcity of other data on protests and strikes in China, the CLB’s data can be used to catch a glimpse into otherwise obfuscated happenings. Analyzing the distribution of protests and strikes over time, the rise and fall in frequency around the beginning of 2016 is especially noteworthy.

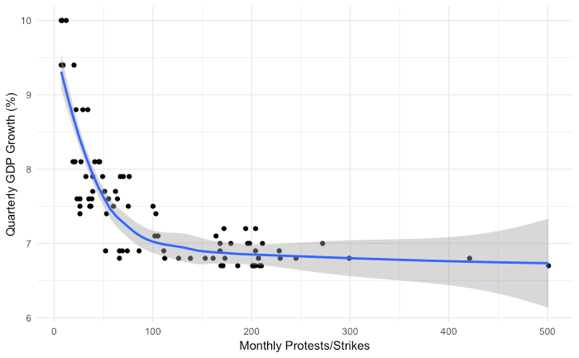

This rise in protest frequency takes place around the same time that China’s economic growth rate dipped. Pursuing this further, and aggregating the data by month, there is a clear and negative correlation between quarterly GDP growth and monthly protest and strike frequency. In other words, as China’s economic growth slows, the number of workers protests increases. The direction of the correlation is contentious: while a declining economy may cause more protests, more protests may also cause a declining economy.

Research by John Dinardo and Kevin Hallock indeed suggests that strikes have historically had the capability of impacting industry stock values. By analyzing U.S. stock market responses from 1925-27, they found that longer, more violent, and industry-wide strikes were associated with negative share price reactions. This may not apply to China, however: previous analysis I conducted with Cole Tanigawa-Lau after the Umbrella Movement protests in Hong Kong found that there was no discernable stock reaction attributable to the protests. Similarly, while there are tens of thousands of protests, there is not yet clear evidence that the protests are the causal factor in declining GDP growth rates.

Most analysts project that the Chinese economy will slow down in the coming years. If the trend over the past seven years continues, the slowed economic growth will lead to more protests. As many political scientists have noted, because protests in non-democratic regimes are one of the few ways to usurp power, this is reason for concern for the Chinese government. Indeed, if this data is correct and there was a spike in protests during the end of 2015 and beginning of 2016, this could have been one of the contributing reasons why Xi Jinping was awarded unprecedented levels of power in post-Mao China.

Despite the rising protest frequency, the chances of protests leading to a change in China’s government are slim. Compared to the Arab Spring protests, for instance, there is no shared political view unifying protesters against the government. The Chinese government has also made headlines for its investments in population-control measures, using new technologies to keep track of movements, both physical and online. Still, rising rates of protests may be a harbinger for larger and more impactful protests to come.

Tyler Headley is a research assistant at New York University. His writing has appeared in publications including Foreign Affairs and The National Interest.