On September 21, China’s Ministry of Justice published its draft Atomic Energy Law, which urges its vast nuclear industry to go forth into the world and secure a portion of the nuclear export market. Unlike the “Gold Standard” interpretation of the “1+2+3” agreement in the U.S. Atomic Energy Act of 1954, China will not officially limit a partner country’s access to the full nuclear fuel cycle in exchange for nuclear cooperation.

This is an important distinction and is the same policy that Russia subscribes to in its nuclear export agreements. While both countries may not be willing to export enrichment technology, they will not explicitly state this or preclude any future partnership on the nuclear fuel cycle. Nuclear exports are an extension of their foreign policy as they seek to secure long-term geopolitical influence and they are signaling that negotiations are always on the table with the Global South.

China’s proliferation policy until Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 “reform and opening up” policy was characterized by countering the imperialist powers, and it stood firm with the Third World, arguably advocating proliferation. China now boasts a solid reputation against proliferation and support for the nuclear order, but it has shown a flexibility to negotiate with all actors; this causes concerns for the nonproliferation regime. The nuclear order currently relies on multinational efforts to constrain with whom a supplier state can partner, but this top down perspective challenges China’s nuclear energy promises to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, including Iran.

China has a unique opportunity to capture a significant portion of the nuclear export market because of their finance schemes and domestic experience. However, MENA states will view China as underperforming in its diplomatic promises if collaboration does not turn into geopolitical gains or enhanced security assurances. China’s efforts to influence the international order will find an audience in the MENA region as states hedge their bets against a distracted and noncommittal United States, but China will not be coaxed into overextension to prove their geopolitical worth — to the distress of MENA states.

The Onus is on the Supplier

China and Russia dominate the civil nuclear import conversation among the MENA states because, for many, the United States’ nuclear export doctrine equates to removing it from the running. The United Arab Emirates are the only MENA country to sign the gold standard U.S. nuclear agreement, which precludes them from the full nuclear fuel cycle and ensures there cannot be any military dimensions to nuclear cooperation. Even though they have no intentions of completing the nuclear fuel cycle soon, many MENA states refuse to sign this interpretation of the U.S. agreement simply to preserve their sovereign rights guaranteed to them under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Concerns about Russian and Chinese nuclear exports to India and Pakistan respectively are cited as evidence of their violations of the supplier nuclear order. India and Pakistan remain outside the NPT, possess nuclear weapons, and both desperately want to be normalized and accepted into the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). The NSG represents the most stringent multinational body that places restrictions on supplier states’ nuclear exports and acceptance to it bestows nuclear prestige. The NSG was initiated largely in response to India’s 1974 nuclear explosive test, but NSG sanctions were lifted on India in 2008 and China’s recent deals with Pakistan are strictly civilian; China is proving its credentials.

China’s “1+2+3” Framework

At the sixth ministerial meeting of the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum in 2014, President Xi Jinping gave a speech identifying his strategic vision for energy collaboration as the “1+2+3” cooperation pattern. The first step refers to energy cooperation primarily on oil and natural gas; the second to the two wings of infrastructure construction and trade and investment facilitation; the third to high-tech collaboration on nuclear energy, space satellites, and new energy.

Civil nuclear cooperation is officially a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and combating climate change is central to China’s pitch. MENA states are very concerned about climate change and shoulder the refugee burden from the Syrian crisis as the West observes a rise in populism and calls to build walls. China seeks to connect infrastructure across borders and create a network of reliance while positioning itself as a leader in the Paris Climate Agreement.

China Zhongyuan Engineering Corporation (CZEC) is the overseas nuclear project platform of China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) – one of China’s central nuclear companies. CZEC markets itself as: “The SOLE exporter of the complete nuclear industrial chain in China; the FIRST overseas nuclear project constructor in China; the LARGEST overseas nuclear project contractor in China.”

CZEC has established offices in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Algeria, which demonstrates a degree of seriousness about its nuclear export intentions to the MENA states along the BRI. China elevated its Hualong One nuclear reactor to the status of high-speed rails as China’s “business card,” meaning MOUs are signed, a framework is created granting the Chinese access to key decision-makers, and thus the door is opened for negotiations on other BRI projects.

The MENA countries are used to the geopolitics of oil and natural gas, weapons imports, and military bases and they have used these deals to hedge their bets against the strategic goals of regional and foreign powers. These tools of statecraft have blocked criticism of human rights violations and prevented intervention (with varying success) from professed leaders of the rules-based international order, and the BRI’s bilateral and multilateral agreements move this from an implied agreement to a formalized ranking of priorities. China focuses the principle of “noninterference in internal affairs” squarely on so-called domestic humanitarian violations, which enables illiberal democracies. But when crisis arises, will China’s geostrategic moves protect its investments?

Noninterference policy and Overextension

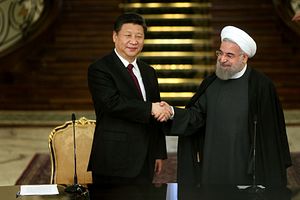

Iran and China signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2016 and article 17 highlighted their attention to a new geopolitical paradigm:

17. Both sides reaffirm their support for the multi-polarization process of the international system…[and] non-interference in the internal affairs of countries…[and] oppose all kinds of use of force or threatening with use of force or imposition of unjust sanctions against other countries as well.

The White House’s increasingly hostile rhetoric and actions toward Iran – including pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal and the 1955 Treaty of Amity, imposing oil sanctions set to begin anew in November, and creating an Iran Action Group – set the stage for greater conflict and chaos. If regime change becomes U.S. policy, then Tehran’s first calls will be to Beijing and Moscow. However, even with the U.S. presence in the MENA region receding due to a citizenry disturbed by U.S. actions and trillions of dollars spent with little domestic benefit, China is unlikely to guarantee Iran security assurances.

Iran sought to cement security assurances from China and Russia by hosting the first Regional Security Dialogue on September 26, but little emerged that could dissuade an aggressive United States. China continues to nimbly maneuver through the Gulf crisis by pursuing counterterrorism operations with Qatar, signing $70 billion in deals with Saudi Arabia, and advancing BRI and free trade zone negotiations with the Gulf Cooperation Council when many in the West have relegated that Council to history.

China wants to sustain economic and diplomatic relations through crises of leadership turnover, authoritarian rule, and humanitarian violations. However, infrastructure is one of the first targets in a crisis and China is hardly in a place to threaten military action against the United States as a form of deterrence. China’s efforts to create a multipolar world do not include security assurances to turbulent regions, but economic incentives are meant to secure influence. China’s military is operating very selectively in Syria and it intends to expand its capabilities, but it will not be coaxed into competition with the United States just yet.

Conclusions

Momentum on regulating China’s nuclear industry increased with China’s Nuclear Safety Law entering into force on January 1, 2018 and the State Council’s issuance of guidelines for the standardization of the nuclear system in August. China’s domestic nuclear expansion has stalled since 2016 so it must expand to new markets and increase its bureaucratic efficiency to support its massive nuclear industry.

China will not upset the nuclear order and prefers to retain the onus of preventing proliferation on the supplier state because that gives it leverage. It is distinctly not in China’s interest for any new nuclear states to crop up and maintaining a little ambiguity in its nuclear export policy allows it to pay lip service to the Global South and keep the West engaged in improving the nuclear order.

As states are ever-evolving, so too is the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Arguably the nuclear order’s greatest achievement is its ability to adapt to new challenges and this is only successful when the world engages.

We can expect that China will continue to set up nuclear export offices and slowly expand their nuclear presence. Nuclear power is a decades-long process for nuclear newcomers and making nuclear an integral part of the BRI shows that this project intends to expand for decades. Promise fatigue is real, and the excitement surrounding the BRI could wither if there are not immediate results, but climate change is petrifying and will keep MENA states interested in Chinese nuclear for many decades to come.

Samuel Hickey is a visiting researcher at the Arab Institute for Security Studies in Amman, Jordan. His research focuses on nuclear diplomacy in the Middle East and North Africa.