Sri Lanka is a middle-income country that is strategically located in the Indian Ocean. It emerged from a three-decade civil war and is now in a post-conflict era, struggling to maintain internal political and economic stability while maintaining friendly relations with the world. But Sri Lanka’s strategic location has led to geopolitical tensions among major powers, all seeking to further their ambitions in the Indian Ocean. Sri Lanka has thus seen the construction of Chinese funded ports, Indian management of national assets such as the Mattala airport, and Japanese aid.

Throughout its long battle with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE), the Sri Lankan government received considerable amount of military equipment by way of sales from China, Pakistan, Russia, and Israel. After the defeat of the LTTE, Sri Lanka has no conventional military threat to face, but instead has to face many nontraditional security threats such as cyberattacks, piracy, illegal fishing, marine pollution, illegal migration, trafficking, and smuggling of illegal contraband, transnational organized crime, etc. Sri Lanka as a small island state has limited resources to counter these threats and against the current economic backdrop, foreign assistance is required – and it must be handled cautiously. Sri Lanka’s ability to obtain military equipment via credit lines is limited while donations are not always given in good faith. Hence, knowing how to strategically balance the receipt of donations and grants could be useful to Sri Lanka when facing the geopolitical game.

Sri Lanka’s Military Capability and Recent Military Donations

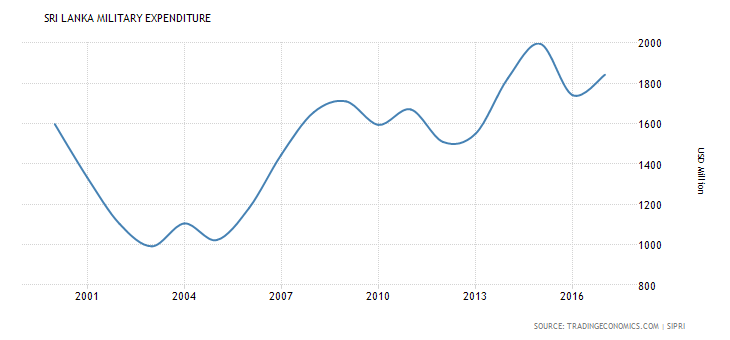

Sri Lanka’s military expenditure has seen an increase even after the end of the civil war in 2009. This is due to the need to maintain the troops and updated equipment, as well as the addition of new institutions over the years. The Sri Lanka Army, Navy, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Civil Security Department have both recurrent and capital expenditures, which even today account for the highest allocations of the budget.

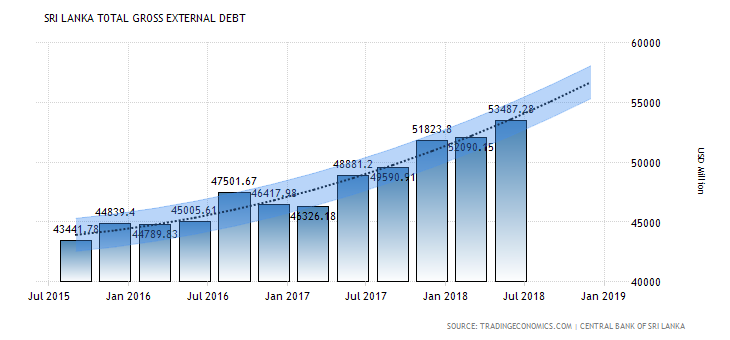

The current debt situation in the country is worse and is predicted to increase over the next years unless the government opens up new avenues for bilateral trade and more investment opportunities, allowing Sri Lanka to gain revenue by being part of global value chains. Although Sri Lanka’s vicious cycle of debt began with the previous government initiating large scale infrastructure developments, the present government’s mismanagement has resulted in the country falling even deeper into debt. As the Institute of South Asian Studies has highlighted “in 2015 [the first year of the Sirisena administration], outstanding domestic debts rose by over 12 percent due to excessive government spending and foreign debt had increased by 25 percent by the end of that year.” Against such a backdrop, Sri Lanka is unable to enter into any agreements to acquire defense equipment via credit lines — no matter how important and necessary that equipment might be.

Strategizing Donations and Grants

Against this pitiful economic backdrop, Sri Lanka has very little choice but to accept military donations. In this year alone, China gifted Sri Lanka a frigate, and Zhou Chenming, a Beijing-based military commentator has predicted that “it is possible China will give [Sri Lanka] one or two more.” Also in 2018 Japan donated two coast guard patrol vessels, SLCGS Samudra Raksha and SLCGS Samaraksha to Sri Lanka. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is also to provide a grant aid of 1.83 billion yen ($16.3 million) for the Project for the Maritime Safety Capability Improvement. Furthermore, the Australian government has provided two main engines for the Sri Lanka Navy Ship (SLNS) Mihikatha, which was a gift to Sri Lanka by Australia. Australia-Sri Lanka defense ties have been lucrative since 2013, when navy boats were donated to prevent human smuggling via maritime routes. India has also been quite active, providing both gifts of vessels as well as training for members of the Sri Lanka Coast Guard on ship handling, bridge navigation, engine room controls, and machinery.

But all these donations, gifts, and capacity building have been subject to various criticisms. These criticisms span anti-military sentiment by the Tamil diaspora and also concerns from domestic interests groups in Sri Lanka, as in the case of U.S. assistance. The Trump administration’s foreign assistance of $3.4 million was criticized for being a tool of U.S. foreign policy, with the goal of to maintaining U.S. dominance in the Indian Ocean region. The United States is also developing ties with the Sri Lanka Navy for conducting training and joint exercises. Sri Lanka must be clear-eyed: extraregional powers providing such assistance do so not entirely for charitable purposes but to also strengthen their own security and power.

Interestingly, the main donations in the maritime sphere for Sri Lanka have come from countries of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue: the United States, Japan, Australia and India. This informal alliance has mainly been viewed as an attempt to control the rise of China. However, there are scholars who promote the idea that Quad countries should work together to promote freedom of navigation in the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion

Countries will continue to engage in providing aid and assistance to Sri Lanka, whether their motives are pure or not, and Colombo has little choice in whether or not to accept such assistance owing to the current economic crisis. Sri Lanka should obtain donations, but with careful assessments of the benefits to the country’s security forces, as well as a careful reading into any legal agreements that might accompany even grants and donations.

Let us consider a hypothetical scenario: two countries have both expressed the intention to donate a surveillance frigate, but Country X has a condition that its engineers can engage in repairing and maintaining the surveillance equipment, and Country Y has no such condition attached. Choosing Country Y over X is a wiser choice, even if Country X is more powerful in terms of bargaining power and has better quality equipment. In this way, Sri Lanka can restrict conditions that might involve a subtle element of foreign intervention.

Having thus concluded, Sri Lanka does not have capacity to build its own weapons, ammunition, and vessels but may look into avenues that will enable them to join a value chain within a global or regional military industrial complex.

Natasha Fernando is Research Assistant at the Institute of National Security Studies, think tank of the Ministry of Defense, Sri Lanka. These opinions do not reflect the Government of Sri Lanka. Her views are independent.