In India, nine out of 10 legislators are men.

While Indian politicians are eager to talk about women’s empowerment and the political legacies of India’s female politicians like Sushma Swaraj, Indira Gandhi or Pratibha Patil, these women remain largely anomalies in the Indian political landscape rather than the norm.

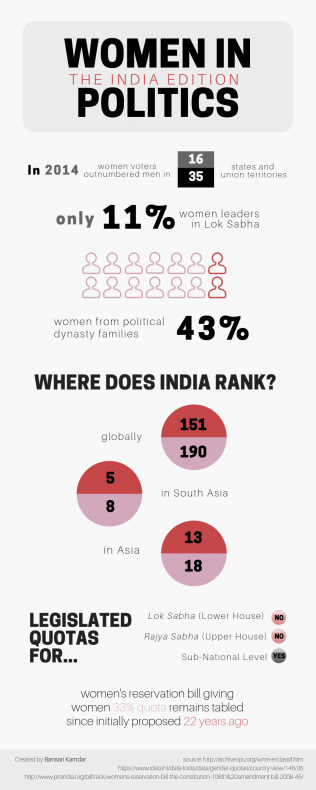

As of 2014, women make up only 11.8 percent of the Indian Lok Sabha and 11.4 percent of Indian Rajya Sabha, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Among its South Asian neighbors, India ranks fifth in women’s political representation in parliament falling behind Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal.

On the other hand, while so many countries around the world grapple with the idea of a female head of state, India was the second country in the world to elect a female head of state, Indira Gandhi. Presently, women in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s cabinet lead some of the most important ministries, from defense to foreign affairs.

Yet still, cases of violence against women increased by 40 percent from 2012 to 2016, according to the National Crime Records Bureau. A woman was raped every 13 minutes, a bride was murdered for dowry every 69 minutes, and six women were gang-raped every day in India in 2016.

Yet still, cases of violence against women increased by 40 percent from 2012 to 2016, according to the National Crime Records Bureau. A woman was raped every 13 minutes, a bride was murdered for dowry every 69 minutes, and six women were gang-raped every day in India in 2016.

Politically, women have been making their presence felt in voter turnouts.

According to the Election Commission data from 2014 General Elections, the female voter turnout was higher than male turnout in 16 states and union territories out of 35.

However, women remain underrepresented in state and national decision-making bodies.

India’s handful of female politicians have occupied some of the highest seats of power but their rise, like many of their counterparts in Asia, has often been through patronage or family legacy.

Research by Amrita Basu in Kanchan Chandra’s Democratic Dynasties : State, Party and Family in Contemporary Indian Politics finds that 43 percent of the women elected to Lok Sabha had family members precede them in politics.

Comparatively, only 19 percent of male MPs were from dynastic families.

The Women’s Reservation Bill

The barriers to entry for female politicians are much higher as they contend with multiple other surface and structural issues.

According to the Economic Survey 2018, prevailing cultural attitudes regarding gender roles, domestic responsibilities, female illiteracy, lack of confidence or finances and the threat of violence, are just some of the obstacles women face.

One way to combat this disparity is through quotas.

In 1994, India ratified the 73rd and the 74th amendments to the Indian Constitution, granting women 1/3 reservation in rural and urban democratic bodies.

This was followed in 1996 by the introduction of the Women’s Reservation Bill that would reserve 33 percent of seats in Lok Sabha and the state legislative assemblies for women on a rotational basis.

After much contestation, the bill finally passed in the Rajya Sabha in 2010 but lapsed in 2014 with the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha. It continues to languish — 22 years since the initial proposal.

Representation matters

Women leaders of panchayat (village councils) often serve as positive role models for many girls.

Research by Lori Beaman, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande, and Petia Topalova finds that in villages with reserved quotas for women, the gender gap in aspirations of girls and boys between 11-15, closed by 32 percent in the girls and by 25 percent in their parents.

The role model effect also erases the gender disparity in educational attainment of young girls.

While quotas allows women access to positions of power, according to some detractors, they also weaken the ideas of election based on merit in democracy. There is concern that women in government may compromise growth as pro-female and pro-family policies are often associated with welfare.

United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research’s (UNU-WIDER) work last year with data from 4,265 state assembly constituencies across four election cycles refutes this claim. UNU-WIDER found that female representatives report a higher economic growth, about 1.8 percent more annually, than male legislators. It also noted that women are more effective at building infrastructure and completing road projects. Women panchayat leaders are more likely to invest in priorities for women because they understand and share these priorities

This supports previous findings by IndiaSpend, that reported women panchayat leaders in Tamil Nadu invested 48 percent more money than their male counterparts in building roads and improving access. Another study by the United Nations found that women-led panchayats delivered 62 percent higher drinking water projects than those led by men.

Ejaz Ghani, William Kerr and Stephen O’Connell also reported a 40 percent increase in new women-owned establishments after the introduction of quotas in the 1994-2005 period.

However, many women run for the local governments, because of pressure from relatives eager to keep a particular seat in the family or gain material benefit. Their spouses, the “panchayat patis,” often control the position, wielding power through the women’s position.

Mona Lena Krook in her renowned book Quotas for Women in Politics observes that while many women may start as proxies to husbands or other family members, they become increasingly effective and independent policymakers as they gain more experience.

Furthermore, once elected, women often run again for political office even after after their constituencies have been de-reserved.

While the reservation for women is only for 33 percent of the seats, women make up 46 percent of the elected representatives in Panchayati Raj institutions, exhibiting active participation and leadership at local government levels.

The Politics of Representation: Rhetoric V. Reality

Presently, the two largest political parties of India, the incumbent Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC), support the women’s reservation bill in their rhetoric.

However, contrary to the popular rhetoric of support, India Today finds that in the 2014 General Elections, BJP gave only 8.8 percent tickets to women candidates and Congress just 12.9 percent.

On October 4, The Times of India reported that BJP is planning to field at least 25 percent women candidates in Madhya Pradesh for the 230 seats. BJP’s past record, however, remains shoddy record.

In the Karnataka elections in May only 6 of the 224 candidates fielded by the BJP were women, less than 3 percent of their total candidature. Ironically, one of Prime Minister Modi’s slogans as he kicked off the state election campaign was, “Beta, Beti Ek Saman” (Son and Daughter are equal).

The other two big parties in Karnataka elections didn’t fare much better when it came to representing women. The INC and the JD(S), fielded 15 and 4 female candidates respectively.

In August, the INC president, Rahul Gandhi, penned a scathing letter to Modi urging him to “walk his talk” on women’s empowerment and pass the bill.

Like BJP, in practice, only 14 percent of the newly formed Congress Workers’ Committee leaders are women, despite the constitution of the INC calling for 33 percent reservation for the party’s committees.

Studies show that for women to have a meaningful impact in Parliament, they need to reach at least a 30 percent threshold.

At 11 percent, India continues lags behind.

Bansari Kamdar is a freelance journalist based in India. She writes on South Asian political economy, gender and security issues.