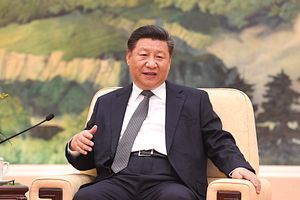

Last month, newspapers showed photos of Xi Jinping surrounded by smiling workers in northeast China. The New York Times published an interesting report likening the images to propaganda posters of Mao Zedong rousing support in the countryside. Xi’s so-called “inspection tour” painted an image of a leader who is of the people, who dreams of a better China and a better life for all Chinese. The parallel drawn by the article is an important one, but the messaging and reminders of Mao are not the only important aspects of the trip. The region Xi chose for the tour holds a special significance that is easily overlooked outside of China.

As Xi stood in northeast China – Manchuria – calling for the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” the location was the first thing I noticed. The region has a long and storied history, but that is actually a large part of the problem – Manchuria suffers from an overabundance of historical significance. It is often a plot point in larger wars and sagas; the region has a history of being used and then abandoned. As someone whose parents were both born in Manchuria, I am left wondering if Xi truly cares about the region, or if he will discard it in the same way his predecessors had.

I grew up with conflicting memories of Manchuria – the region that is now made up of Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces. My father was proud of his heritage. He was loyal to Manchuria and his greatest dream was to see his home region prosper. At the same time however, I was told as a child living in Beijing not to tell people I was Manchurian. I was warned that I would be looked down on and judged. This mixture of pride and caution goes a long way toward explaining the unique situation Manchurians find themselves in. They love both their region and their country, but they are left uncertain whether their country loves them in return.

Manchuria was the birthplace of China’s final imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911). It was a dynasty led not by the majority Han Chinese but by the Manchurian minority. But even though China was under Manchu rule, Manchuria itself was still forced to cede to outside influence. Russians and Japanese both saw Manchuria as a prize to be won. The Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) was fought inside Manchuria. My mother, who grew up in Liaoyang county, told me her parents cut her hair during the war in hopes that if the Japanese and Russian troops saw her, they would think she was a boy – saving her from being raped. Ultimately, it was U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt, not the Qing rulers, who helped broker peace with the Treaty of Portsmouth. His efforts earned him the distinction as the first American recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

When the Chinese Revolution toppled the Qing dynasty and Manchu rule in 1911, Manchuria stayed largely separate. It was controlled by one of the most powerful military warlords during the warlord era (1916-28) before China was finally reunified under the Republic of China. But all too soon, in 1931, the Japanese attacked and occupied the Manchurian city of Shenyang. By the next year, they had formed a puppet state, Manchukuo, encompassing all of occupied Manchuria. At the end of World War II, the Soviet Union staked a claim on Manchuria and captured it from the Japanese. They looted and plundered the region, not caring about the damage left in their wake. With Soviet backing, the Chinese Communists occupied Manchuria and the region was a key base in the civil war against the Nationalists.

Through all of these historic events, the people of Manchuria were, to most, just an afterthought. Manchuria was simply a football being kicked around from person to person. It was a necessary tool to score points and win the game, but no one cared if it got scuffed or damaged in the process. And, if the ball became too damaged to score points with, it was simply discarded and forgotten. Even during the Qing dynasty, Manchuria – the birthplace of the Qing – was left to be fought over by outside interests.

Manchuria’s fate during the Second Sino-Japanese war serves as a stark example of how the region has been used and abused by China’s leaders in the past. My father, General Wang Shuchang (1885-1960), was an adviser and military commander for the Old Marshal Zhang Zuolin (1875-1928), the warlord who controlled Manchuria until he was killed by a Japanese train bomb in 1928. My father went on to advise his son, the Young Marshal Zhang Xueliang (1901-2001), and encouraged unification with the rest of China, then under Nationalist control.

The Nationalists, under Chiang Kai-shek, were happy to have the strong Manchurian military forces at their disposal. After all, they were in the middle of a conflict with the Chinese Communists. When the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, however, Chiang decided it was simply not worth fighting for and refused to send troops to protect the region. When Chiang continued to focus his attention on the Communists instead of the Japanese, Zhang Xueliang finally had enough. In what has famously come to be called the Xi’an Incident, he kidnapped Chiang and forced him to agree to stop fighting the Communists and form a United Front against the Japanese. This event is often cited as one of the main contributing factors allowing the Communists to regroup and ultimately defeat the Nationalists.

I met with Zhang Xueliang often in his final years. He told me he regretted that his actions had made him an enemy of the Nationalists. He was not trying to take sides in the civil war. He simply wanted to fight the Japanese and reclaim his homeland, but he seemed to be the only one making Manchuria a priority. He had little choice but to force others to listen. Zhang Xueliang’s actions left him exiled from his home and under house arrest for more than 50 years. He never did return to Manchuria.

Underlying Chiang’s easy dismissal of Manchuria was fear for his own personal power. Manchuria had been all but separate from the rest of China, under the command of Zhang Zuolin and then his son. Chiang feared Manchuria would break off from the rest of China, taking power and troops away from Chiang. Echoes of that fear can be seen in recent years as well. Before more famously serving as the party secretary of Chongqing, Bo Xilai was the mayor of Dalian, a major Manchurian city. Under his leadership, Dalian prospered, and Bo later became the governor of Liaoning province. But as his own personal power grew, he was seen as a potential competitor to the leadership in Beijing and soon became the first high profile target of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign.

With this history in mind, Xi’s trip to northeast China takes on new meaning. These are not just random cities he visited – they have strategic and historical resonance. It is no coincidence that Xi chose Manchuria as his location to speak words of revitalization and of a shared better future for all of China. Manchuria is so often the region in China used by outside countries and overlooked by the Chinese. His presence there signals to the world, and especially the countries who previously fought over Manchuria, that China is powerful enough to focus on even its most often forgotten regions.

Hopefully, Xi will follow up his words with actions. A revitalized and integrated Manchuria would be a poignant symbol of a united and strong China.

Dr. Chi Wang is President of the U.S.-China Policy Foundation and previously served as the head of the Chinese section at the Library of Congress.