Irrespective of what the United Nations says, on November 16, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), better known as the Khmer Rouge war crimes trial, will hand down their final verdicts. Like most of the UN war crimes trials since the end of the Cold War, the legacy of the ECCC is part good, part bad, and part ugly. In the end, the $300 million dollar court took longer to convict three defendants than it did for the United States, England, and France to try nearly 5,000 war criminals after World War II. Within the spectrum of political justice the ECCC stands above farces like the American “trials” at Guantanomo Bay or spectacles of primitive political justice like the Yamashita Case, but far below flawed, yet ultimately successful trials like Nuremberg’s International Military Tribunal. It would be easier to consider the ECCC “a success” had its boosters in the UN and the human rights industry not raised expectations so high and oversold it so grossly.

Thirty-nine years ago, the world’s response to Khmer Rouge atrocities shattered the “never again” promise once and for all. In three years, 10 months, and 20 days, the Chinese-backed Cambodian communists killed roughly 20 percent of their population (1.5 to 2 million people). When the Vietnamese tried the Khmer Rouge leaders in absentia in 1979, they were widely ridiculed for their efforts. After the world learned of Cambodia’s “Killing Fields,” China, the United States, and the United Nations protected and rearmed the perpetrators while Western leftists, led by Noam Chomsky, attacked “the extreme unreliability of refugee reports” of crimes against humanity. Although the United Nations spent $2 to 3 billion dollars during their Cambodian occupation (1992-1993), no Khmer Rouge leaders were captured, much less held legally accountable.

Three decades after the crimes, the ECCC, a mixed UN-Cambodian war crimes tribunal, was established to try the regime’s surviving senior leaders. The fact that the surviving Khmer Rouge leaders, Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, and Ieng Thirith, were brought to trial within their lifetimes was very good and silenced longtime critics (like myself) who had to give credit to the ECCC and especially the devoted investigators who worked for decades to bring them to justice. While the UN lawyers and judges were a mixed bag, the generations of investigators, led by Craig Etcheson, Steve Heder, Rich Arant, Sorya Sim and Steve Spargo, did a remarkable job building onto the pre-ECCC research of David Hawk, Ben Kiernan, David Chandler, Youk Chhang, Sara Colm, Helen Jarvis, Doug Niven, Chris Riley, Nic Dunlop, Nate Thayer, Rithy Panh, Elizabeth Becker, and many others.

By far the ECCC’s most important legacy was the creation of an unassailable historical record that will withstand the test of time and make historical revisionism virtually impossible. However clear the historical facts seem to Western scholars, they remain unclear to some Cambodians and for good reason. Over the course of three decades, Cambodians were subjected to the competing and contradictory propaganda claims of the U.S.-backed Lon Nol regime (1970–1975), the Khmer Rouge (1975–1979), the Vietnamese-installed People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989), the State of Cambodia (1989-1992), the United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia (UNTAC) (1992–1993), and since 1993 the iron-fisted Prime Minister Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). It is now clear for all to see, in meticulous detail, who did what to whom.

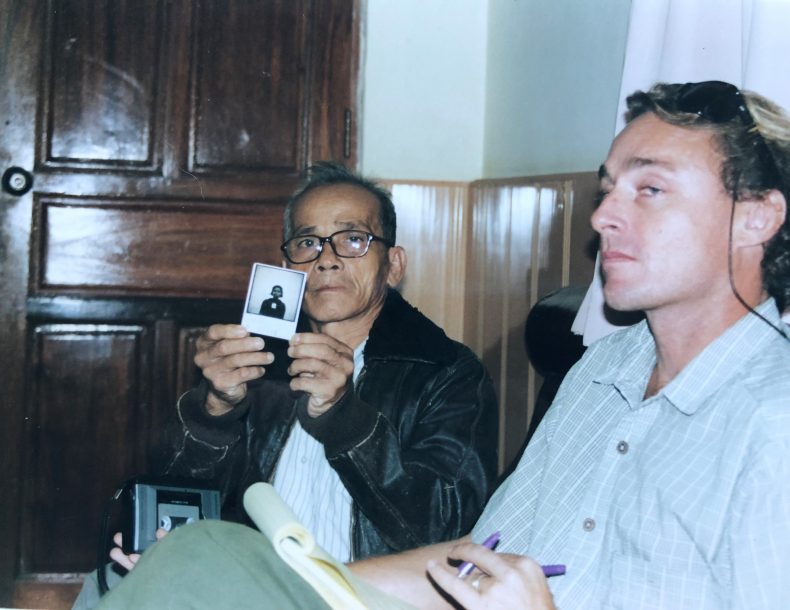

Author Peter Maguire (right) interviewing Tuol Sleng Prison survivor Bou Meng in Cambodia (2003). Photo by Annabelle Lee.

The decision to begin the war crimes trials with the case of Tuol Sleng Prison commandant Brother Duch (Kaing Guek Eav) was a bad one. Although Duch was a blood-stained butcher who ran a prison that 16,000 to 20,000 people entered and less than 20 survived, he was a garden variety war criminal, not a senior leader. Unlike the senior political leaders who denied knowledge of atrocities, Duch, now an evangelical Christian, admitted his guilt. As a result of his confession and the empirical records linking him to the killings at Tuol Sleng, this was the simplest major war crimes trial since Einsatzgruppen leader Otto Ohlendorf and 23 others were tried at Nuremberg. However, the tribunal in the Einsatzgruppen Case took six months to try 24 defendants; the tribunal in the Duch took over a year to try a single defendant.

In the end, this case delayed the proceedings against the senior leaders and only two of the four were tried (defendant Ieng Thirith was declared mentally unfit to stand trial in 2011 and her husband Ieng Sary died in 2013). The ECCC’s failure to complete the trials of indicted senior leaders within their lifetimes raises an important question: Are the UN’s overcomplicated and overpriced trials worth the money, time and trouble if they cannot complete trials while the defendants are alive?

The unbridled arrogance of United Nations officials who acted as if they were honest brokers in Cambodia was ugly. Lest we forget, the UN allowed Khmer Rouge representatives to hold Cambodia’s seat in the General Assembly after it was clear that they had carried out massive atrocities, if not genocide. The UN’s failure to even mention Khmer Rouge war crimes in the Paris Peace Accords, the agreement that paved the way for the UN occupation of Cambodia and the 1993 election, was ugly. It was also ugly that during the United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia’s (UNTAC) occupation, despite the presence of 15,000 troops, could not summon the political will to capture a single war crimes suspect, much less end the civil war.

It is important to remember that Cambodian war crimes trials were not seriously discussed until Prime Minister Hun Sen did something the UN was unwilling to do — he used force and diplomacy to break the back of the Khmer Rouge in 1997. The 1999 recommendations of UN war crimes experts (Steven Ratner, Ninian Stephen, and Rajsoomer Lallah) that the trial be moved out of Cambodia and put under UN control were not only ugly, they reeked of unearned arrogance. Not only did an offended Hun Sen scoff at their seminar room legalism, but he never tired of reminding the UN that during the UNTAC era, “they never talked about trying the KR, [but] they talked about recognizing the KR to participate in a political solution.” In the end, the Cambodian prime minister suggested that the UN’s war crimes experts “end their careers as lawyers and work in politics” and completely rejected their recommendations. After much international legal posturing, the United Nations agreed to a trial in Cambodia with a Cambodian majority at every level.

Once it was clear that mixed UN-Cambodian trials would take place, Phnom Penh was flooded with human rights industry activists who argued that these war crimes trial would do more than determine legal guilt and innocence: trials would bring about a national catharsis. However, claims that war crimes trials lead to healing, closure, truth, and reconciliation are purely speculative. How does one measure “healing, closure, truth, and reconciliation”? If nothing else, the ECCC would test the therapeutic legalists’ broad and unproven claims about “restorative justice” after they established a Victims Support Section (VSS) that permitted “any person or legal entity who has suffered from physical, psychological or material harm as a direct result of Democratic Kampuchea” to testify and seek reparations. ECCC spokesman Neth Pheaktra went so far as to claim, “The tribunal facilitates reconciliation and at the same time provides an opportunity for Cambodians to come to terms with their history.” The VSS faced the same problems as the International Criminal Court in the Lubanga case where the ICC announced reparations for some victims, not others, and infuriated many in the Congo. In the end, the VSS overcomplicated and slowed the trials.

Although therapeutic organs like the VSS have a place, it is not in a courtroom. To ask any court, much less a war crimes court, to heal societies or teach historical lessons is asking too much. To claim that courts executing laws against war crimes can also bring about social and political peace, even if that concept could be defined to everyone’s satisfaction, is delusory.

Once the first trial began, the ECCC attempted to act with autonomy by opening new cases against other surviving Khmer Rouge leaders like navy head Meas Muth. When the Cambodians refused to investigate these new cases, much less carry out arrest warrants, the United Nations should have completed their existing caseload and announced a departure date. Instead, the UN and their allies in the human rights industry challenged Hun Sen and postured as if their power extended beyond the op-ed page of The New York Times. In the end, the ongoing demands for more trials was little more than international legal virtue signaling.

Pol Pot (center) and other Khmer Rouge leaders during a visit to China. Photo from Pol Pot’s personal photo collection.

Throughout the ECCC there has been a Chinese elephant in the room. “When people mention the Khmer Rouge, many might be reminded of the support China once gave it. This is a problem that cannot be avoided. No matter whether China wants it or not, people will allude to that history,” wrote Vietnamese diplomat Ding Gang, “If there is a case to be made, it remains up to the Chinese themselves to make it. Their approach in shutting down Vietnam’s case of Khmer Rouge genocide against Vietnamese civilians is not the way to do it. We are stuck with a Southeast Asia that is afraid to confront, even to discuss, its history. To me, that means more of the same to come.” While the Chinese have maintained that the ECCC was a “Cambodian internal affair,” we need to remember that the Khmer Rouge had no more generous and indulgent patron than the People’s Republic of China.

Although the Khmer Rouge leaders were charged with committing genocide against the Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese inside of Cambodia, conspicuously absent was any mention of the atrocity that ultimately brought down the regime: the massacre of 3,000 Vietnamese in An Giang. Retired Vietnamese diplomats have recently offered more evidence of the Chinese efforts to protect the Khmer Rouge allies. “Truthfully speaking, we were also the victims of Pol Pot’s genocide. When they came across into An Giang, our fellow countrymen were horribly massacred. But for our own sake, for the greater duty, because of major issues, we must let it go,” wrote former Vietnamese President Lê Ðức Anh. While some downplay the Chinese influence on the ECCC, is it a coincidence that the court never hired a Vietnamese-speaking investigator or placed a single Vietnamese interpreter inside the Office of the Coinvestigating Judges?

Many of the war crimes careerists who frequent the revolving door between the UN and the human rights industry standard bearers like the Open Society Institute, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the hundreds of academic human rights think tanks act as if they have rid international criminal law of politics through procedural perfection and that there is such a thing as “international standards” for war crimes courts. After 9/11, not only did President George W. Bush reject both codified (the Geneva Conventions) and normative standards of international law (via the International Criminal Court), many of the world’s powers followed his lead. Even as early as 2002, David Rieff pointed out that “the norms [of international justice] had outstripped the realities to a grotesque degree.” However, rather than face profound questions about the relationship between national sovereignty and “universal jurisdiction,” human rights advocates fell victim to magical thinking. Lawyer, human rights activist, and celebrated author Philippe Sands argued that the ECCC’s success or failure should not be determined by “dollar signs and convictions.” To Sands, “the bigger question” was the extent to which “this tribunal contributed to beginning the process of embedding the idea of justice, the absence of impunity into public consciousness, to help Cambodia transition to a better place.”

Did the Khmer Rouge war crimes trials contribute to “beginning the process of embedding the idea of justice”? Absolutely not. Did the ECCC help “end impunity in the public consciousness”? Absolutely not. Did the court “help Cambodia transition to a better place”? Absolutely not. During the course of the Khmer Rouge war crimes tribunal, Cambodia imprisoned opposition leader Kem Sokha, killed a once vibrant free press, and became a one-party state. However, does that make the ECCC a failure or a farce? Absolutely not.

The ECCC, like every similar effort before it, proved once again that politics are an indelible part of any war crimes trial. Why were trials delayed for three decades? Politics. Why was the genocidal regime allowed to represent Cambodia in the UN? Politics. Why did the ECCC refuse to investigate the Vietnamese massacre in An Giang? Politics. Why did the court overlook the United States’ secret bombing of Cambodia, spearheaded by Henry Kissinger? Politics.

Nonetheless, as overpriced and overcomplicated as ECCC was, thanks to the historical record compiled by generations of valiant researchers, it can be counted as a success. Now it is time for the UN to stop the magical thinking about future trials, confirm the final sentences, and announce a departure date from Cambodia.

Dr. Peter Maguire is the author of Facing Death in Cambodia; Law and War: International Law and American History; and Thai Stick. He has taught the law and theory of war at Columbia University, Bard College, and University of North Carolina Wilmington. He is the founder and director of Fainting Robin Foundation.